William Hogarth, Heads of Six of Hogarth’s Servants c.1750–5. Tate.

Metropolis 1720–1760

16 rooms in Historic and Early Modern British Art

London is the largest city in Europe, a hub of global trade and commerce. Artists such as William Hogarth show us the many sides of urban life

During a period of peaceful economic growth in Western Europe, London becomes a thriving market of commercial exchanges and coffee houses. Along with Bristol and Liverpool, London is also a hub of the transatlantic slave trade. The resulting goods and profits pour into British cities. When war breaks out in 1756, victory over France allows Britain to strengthen its position abroad, expanding its North American colonies and consolidating power in India.

Religious zeal and conflict have receded, while new commercial values hold sway. Wealthy merchants now play an important role in London’s art market, alongside aristocrats and landowners. Artists depict them in small-scale group portraits of family and friends, known as ‘conversation pieces’. This new format becomes a particularly British genre of painting. These fashionable scenes of polite society show a booming consumer culture, derived from Britain’s colonial wealth: tobacco is smoked, tea and coffee are sweetened with sugar, then drunk from Chinese porcelain.

Hogarth’s conversation pieces are celebrated for their informality and vibrancy. His images of bustling city life and his biting satires, which cross social classes, are also hugely popular. While some of the best European artists, such as the Italian painter Canaletto, still come to London, there are also renewed efforts to establish a home-grown British school of painting. This is a cause that Hogarth champions with particular vigour.

William Hogarth, O the Roast Beef of Old England (‘The Gate of Calais’) 1748

This picture is based on a real event when Hogarth was arrested as a suspected spy in Calais while sketching the gate of the fort. Hogarth is visible in the far left, portrayed as a sharp-eyed observer of his surroundings. But the picture also serves as an allegory of English nationalism. It depicts a collection of xenophobic stereotypes, including underfed French soldiers, an exiled Scottish Jacobite rebel, and a greedy Catholic friar. The imported British beef contrasts with watery French soup. The ‘Old England’ in the title alludes to an idea of England as prosperous and harmonious, again in contrast to France.

Gallery label, June 2022

1/28

artworks in Metropolis

Pablo Bronstein, Molly House 2023

2/28

artworks in Metropolis

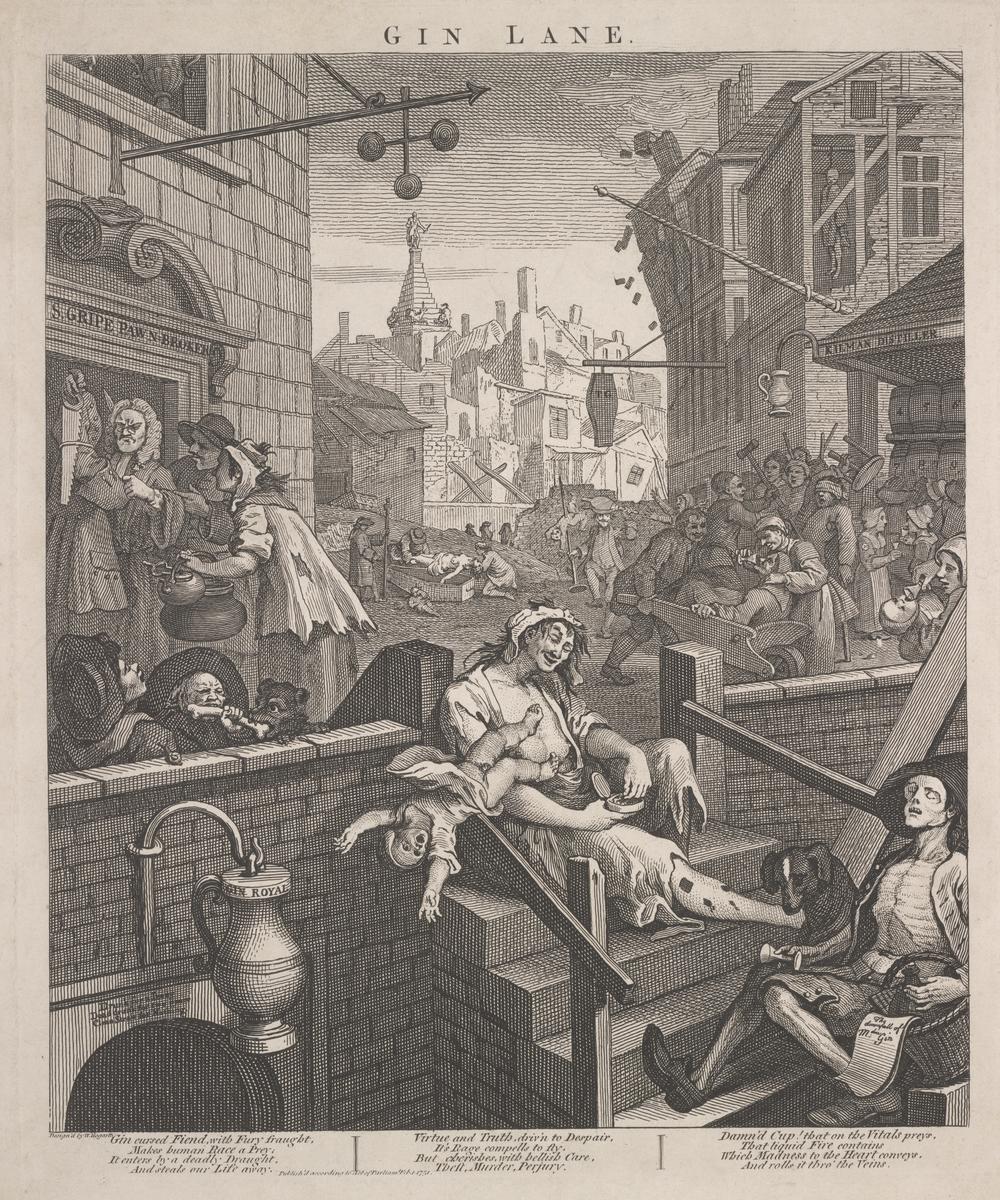

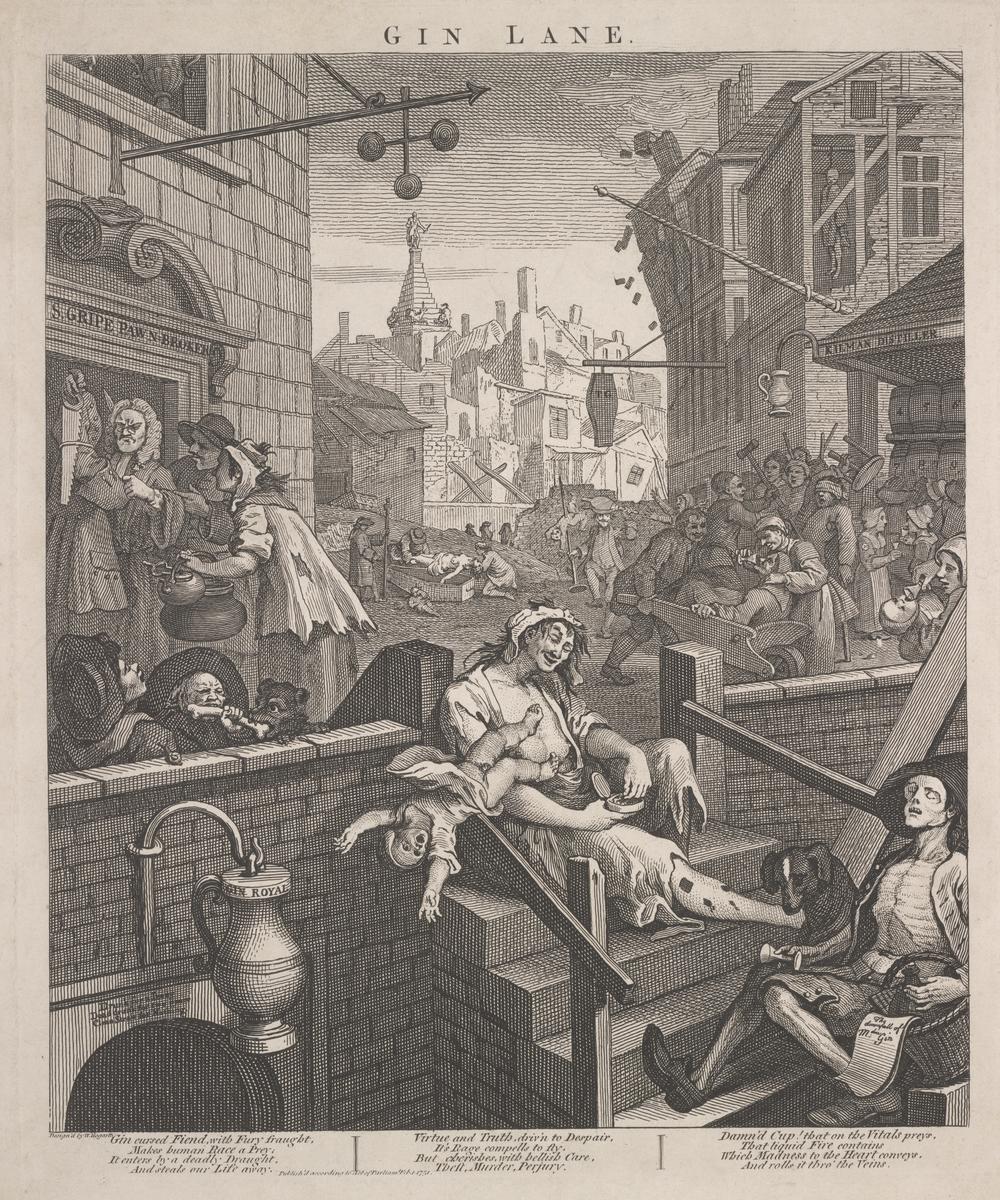

William Hogarth, Gin Lane 1751

3/28

artworks in Metropolis

Richard Wilson, Westminster Bridge under Construction 1744

Wilson painted this view of Westminster Bridge under construction in the early autumn of 1744. The bridge, begun in 1738 and opened in 1750, was one of the major civic projects of the century. It became the focal point of innumerable London views, including the one by Samuel Scott, shown two paintings to the left.

When Wilson painted this picture he was still working principally as a portrait painter. But his attention to the broad sweep of scenery surrounding the bridge, and sensitive rendition of light, show he was profoundly interested in landscape long before he went to Italy in 1750.

Gallery label, September 2004

4/28

artworks in Metropolis

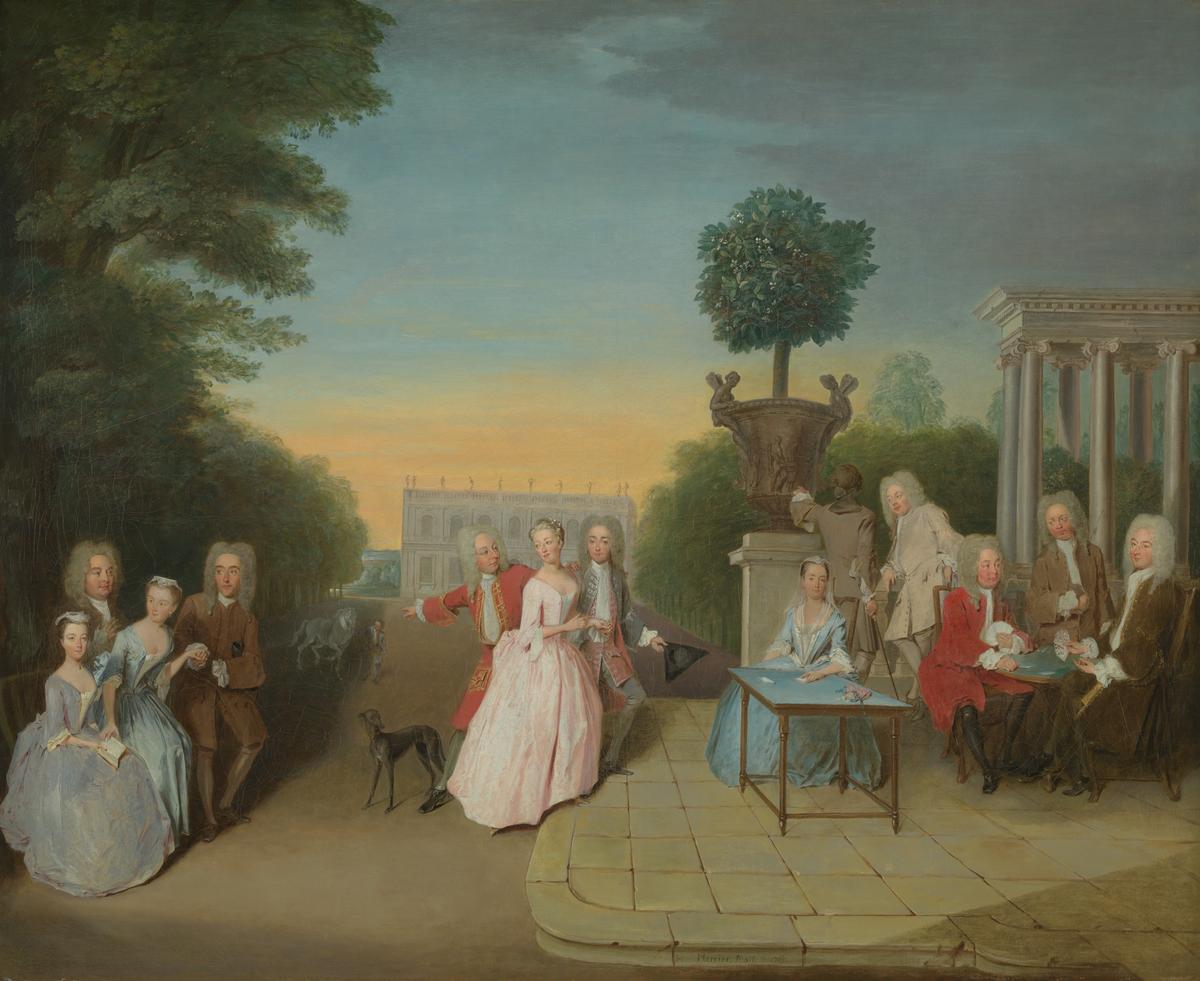

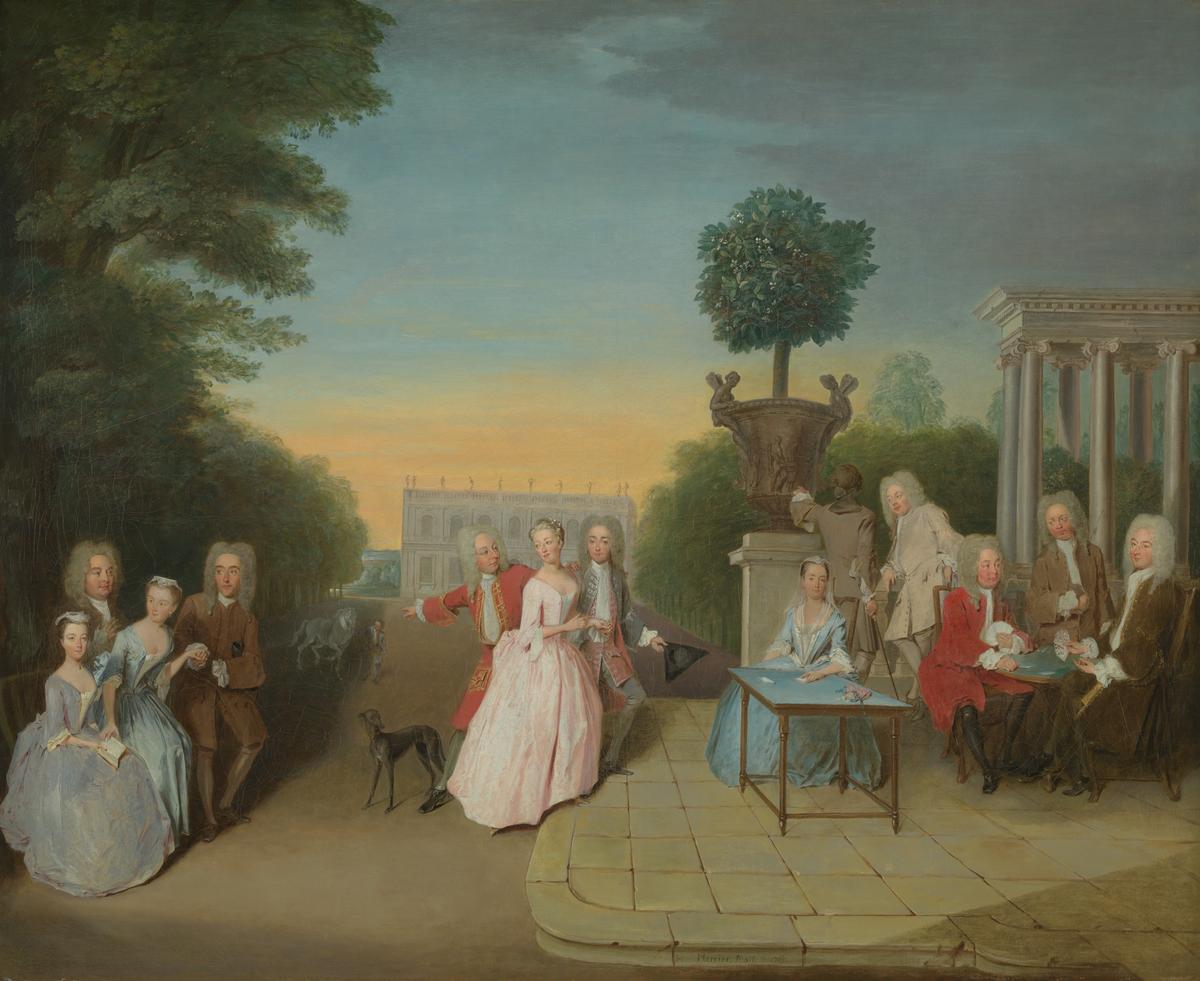

Philip Mercier, The Schutz Family and their Friends on a Terrace 1725

In this emblematic marriage portrait, the groom in the centre, probably Augustus Schutz, leads his bride towards his family as she takes a backward glance at her own. Several members of the Schutz family held positions at the court of Hanover and it may be that this portrait also acts as an endorsement of the Hanoverian succession. Thus, the orange tree in the garden urn may symbolise William III and the House of Orange, while the white horse could represent the House of Hanover, whose heraldic device was a horse courant argent (a silver or white running horse).

Gallery label, February 2016

5/28

artworks in Metropolis

Thomas Gainsborough, The Rev. John Chafy Playing the Violoncello in a Landscape c.1750–2

When Gainsborough painted this portrait John Chafy was in his early thirties and probably still a bachelor. Chafy, who was the vicar at Great Bricett in Suffolk, was also talented amateur musician. Gainsborough too is known to have played several instruments with ‘native skill’ and was an active member of the Ipswich Musical Club.

This portrait was probably painted shortly before Chafy left East Anglia in early I752. In the temple behind him is a statue holding a lyre, the attribute of the Muses of dancing and love poetry. This is probably a reference to Chafy’s forthcoming marriage.

Gallery label, September 2004

6/28

artworks in Metropolis

Sonia Barrett, Lady of the House 2012

7/28

artworks in Metropolis

Thomas Frye, Henry Crispe of the Custom House 1746

This portrait is distinguished by the artist’s fascination with the textures and play of light on the sitter’s clothing. Its style shows how strongly Frye was influenced by Hogarth. Henry Crispe was Registrar of Certificates and Examiner of Debentures at the Custom House, London. He died the year after this portrait was painted. His epitaph records that ‘in him was shewn that polite literature and ev’n a poetical genius best form the man of business’, skills which are indicated in this portrait by the presence of the quill and the writing materials on the table.

Gallery label, August 2004

8/28

artworks in Metropolis

Gawen Hamilton, The Du Cane and Boehm Family Group 1734–5

This formal group portrait is a record of the dynastic union, through marriage, of the financially powerful Du Cane and Boehm families, both of Huguenot (exiled French Protestant) descent. Standing at the centre is Richard Du Cane, flanked by his family, including the couple whose marriage in 1735 united the two families: his daughter Jane and Charles Boehm. The portrait is among Hamilton’s most ambitious compositions and shows why contemporaries regarded him as a serious rival to William Hogarth.

Gallery label, February 2016

9/28

artworks in Metropolis

Samuel Scott, An Arch of Westminster Bridge c.1750

This work celebrates an important event in the history of London: the building of Westminster Bridge. The bridge, shown near completion, was the first to be built over the Thames in over 600 years. During the 11 years of its construction it was painted by many artists, including Canaletto and Richard Wilson. The arrival of Canaletto in England in 1746 may have stimulated Scott to compete by producing similar views of London scenery, particularly along the Thames. Like Canaletto, Scott has included lively figures, shown here swimming, drinking ale and peeping through the balustrade.

Gallery label, November 2016

10/28

artworks in Metropolis

Sonia Barrett, Chair no. 35 2013

11/28

artworks in Metropolis

William Hogarth, The Strode Family c.1738

Hogarth's early success as a painter was based on his exceptionally lively small-scale 'conversation pieces', or informal group portraits, which became fashionable in the 1730s. They reflected the move away from the solemn formality of the previous generation and attempted to show the sitters in easy, natural poses, in a domestic setting, engaged in everyday activities like conversation or drinking tea. The main subject here is the wealthy city magnate William Strode, seated at table with his new wife Lady Anne Cecil, his relative Col. Strode, and his tutor Dr Arthur Smyth, later Archbishop of Dublin. The paintings on the wall are reminders of their recent tour of Italy. On the floor is the tea caddy.

Gallery label, August 2004

12/28

artworks in Metropolis

William Hogarth, A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI 1731

This is one of the first paintings made of an English stage performance. It depicts a climactic scene from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, first performed at the Lincoln’s Inn Theatre in 1728. Here the opera’s central character, a highwayman named Macheath, stands chained, under sentence of death, between his two lovers, the jailer’s daughter, Lucy Lockit, and the lawyer’s daughter, Polly Peachum. At either side of the stage Hogarth has included members of the audience, notably at the far right the Duke of Bolton, real-life lover of the actress Lavinia Fenton, who played the part of Polly Peachum.

Gallery label, February 2016

13/28

artworks in Metropolis

Joseph Van Aken, An English Family at Tea c.1720

This group portrait of an unidentified family and their servants was probably painted soon after Van Aken moved from his native Antwerp to London. Tea was an expensive commodity, as were all the items related to its consumption: the tea table, silver, and porcelain. The tea box is shown in the foreground. Its contents were normally kept locked by the lady of the household, who is shown dispensing the precious leaves from a container.

Demonstrating wealth, domesticity and genteel informality, tea-drinking came to epitomise civilised behaviour in the eighteenth century.

Gallery label, August 2004

14/28

artworks in Metropolis

William Hogarth, The Enraged Musician 1741

15/28

artworks in Metropolis

William Hogarth, Lavinia Fenton, Duchess of Bolton c.1740–50

This is said to be a portrait of the actress and singer Lavinia Fenton (1708–60), who starred as the heroine Polly Peachum in the original and highly successful 1728 production of The Beggar’s Opera. After it closed, Fenton ran away with her lover, Charles Paulet, 3rd Duke of Bolton (1685–1754) and the couple had three sons. When the Duke’s estranged wife died in 1751, the Duke and Lavinia married and she became Duchess of Bolton. This portrait – if correctly identified – shows her in later life. She died in Greenwich in 1760.

Gallery label, June 2018

16/28

artworks in Metropolis

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal), London: The Old Horse Guards from St James’s Park c.1749

Horse Guards, the building with the clocktower in the centre, was the headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief of the army, and housed the horse guards and some foot guards. It was replaced in the 1750s with the white stone building that stands today. Canaletto’s paintings were in demand from rich patrons. However, this work was produced speculatively, possibly in the hope of selling it to a wealthy resident of Downing Street (seen on the right). Canaletto invited prospective buyers to view the painting at his Soho lodgings.

Gallery label, November 2016

17/28

artworks in Metropolis

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal), London: the New Horse Guards from St James’s Park c.1752–3

This painting is closely related to other views of Horse Guards by Canaletto, including the much larger and slightly earlier image which hangs nearby. Here Canaletto shows the construction of the new Horse Guards building, the original red-brick building having been demolished in 1749–50. Much larger than the earlier building and formed of white stone, it was designed in the classical style by William Kent. Wooden scaffolding can be seen supporting the clock tower, and work on the south wing is yet to begin. This is the building that exists to this day.

Gallery label, November 2016

18/28

artworks in Metropolis

William Hogarth, The Painter and his Pug 1745

Hogarth began this self-portrait in the mid-1730s. X-rays have revealed that initially it showed the artist in a formal coat and wig. He later changed these to the more informal cap and clothes seen here. The oval canvas containing Hogarth’s portrait appears propped up on volumes of Shakespeare, Swift and Milton, authors who inspired Hogarth’s commitment to drama, satire and epic poetry. On his palette is the ‘Line of Beauty and Grace’, which underpinned Hogarth’s theories on art. Hogarth’s pug dog, Trump, serves as an emblem of the artist’s own pugnacious character. This portrait acted as a statement of the artist’s professional ambition.

Gallery label, February 2016

19/28

artworks in Metropolis

after Samuel Scott, A View of the Thames with the York Buildings Water Tower ?c.1760–70

20/28

artworks in Metropolis

William Hogarth, Heads of Six of Hogarth’s Servants c.1750–5

This group portrait may have hung in Hogarth’s studio, serving as an advert for his skill in painting. Anyone visiting Hogarth’s house would have been met by his servants. On entering his studio, they could then compare Hogarth’s painted portraits with the real person. The aim would have been to impress, especially anyone considering having their own portrait painted. It demonstrates his ability to capture a likeness in all age groups. Portraits of servants from this period are rare. Hogarth’s decision to paint his servants in this way is unique.

Gallery label, December 2020

21/28

artworks in Metropolis

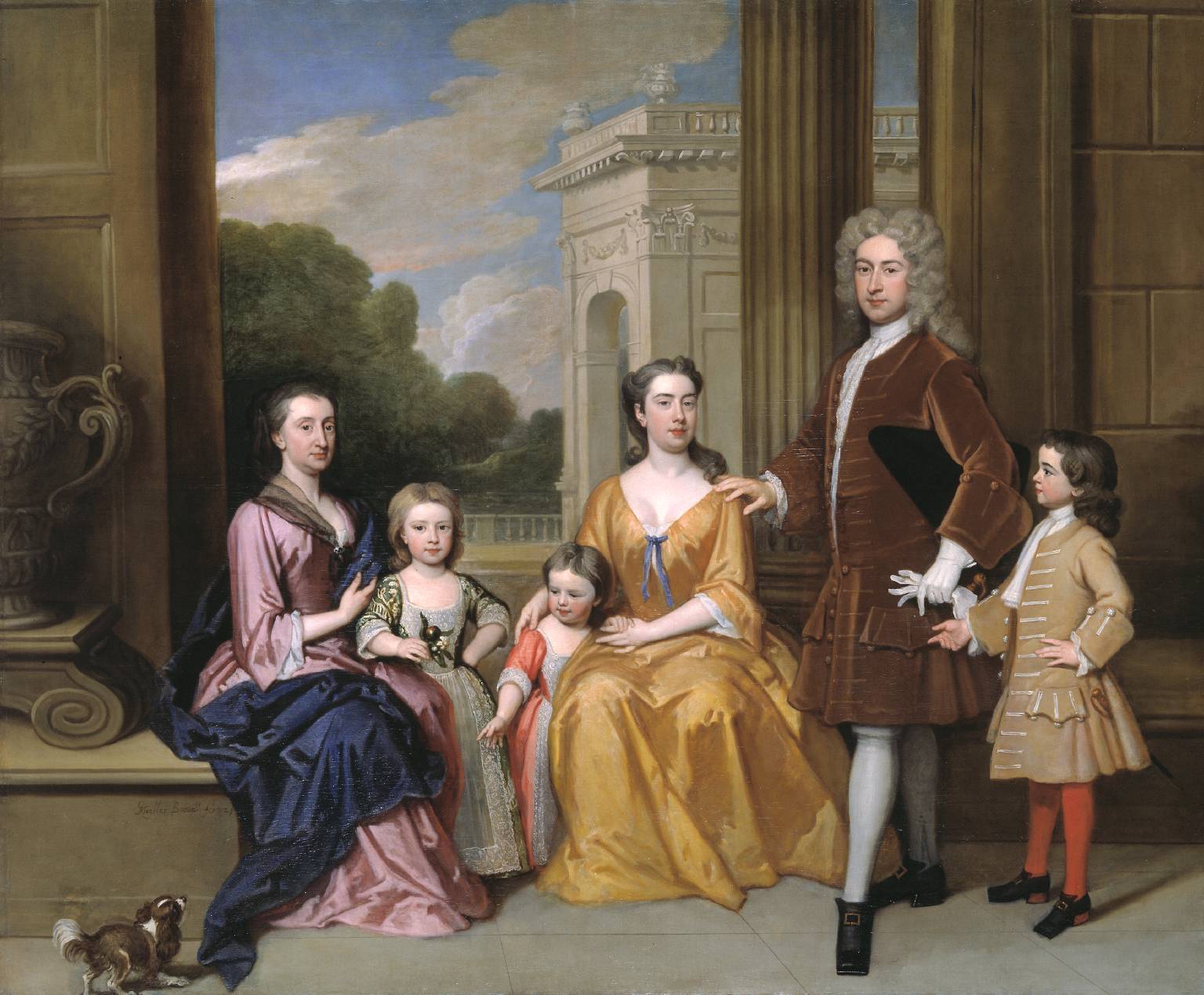

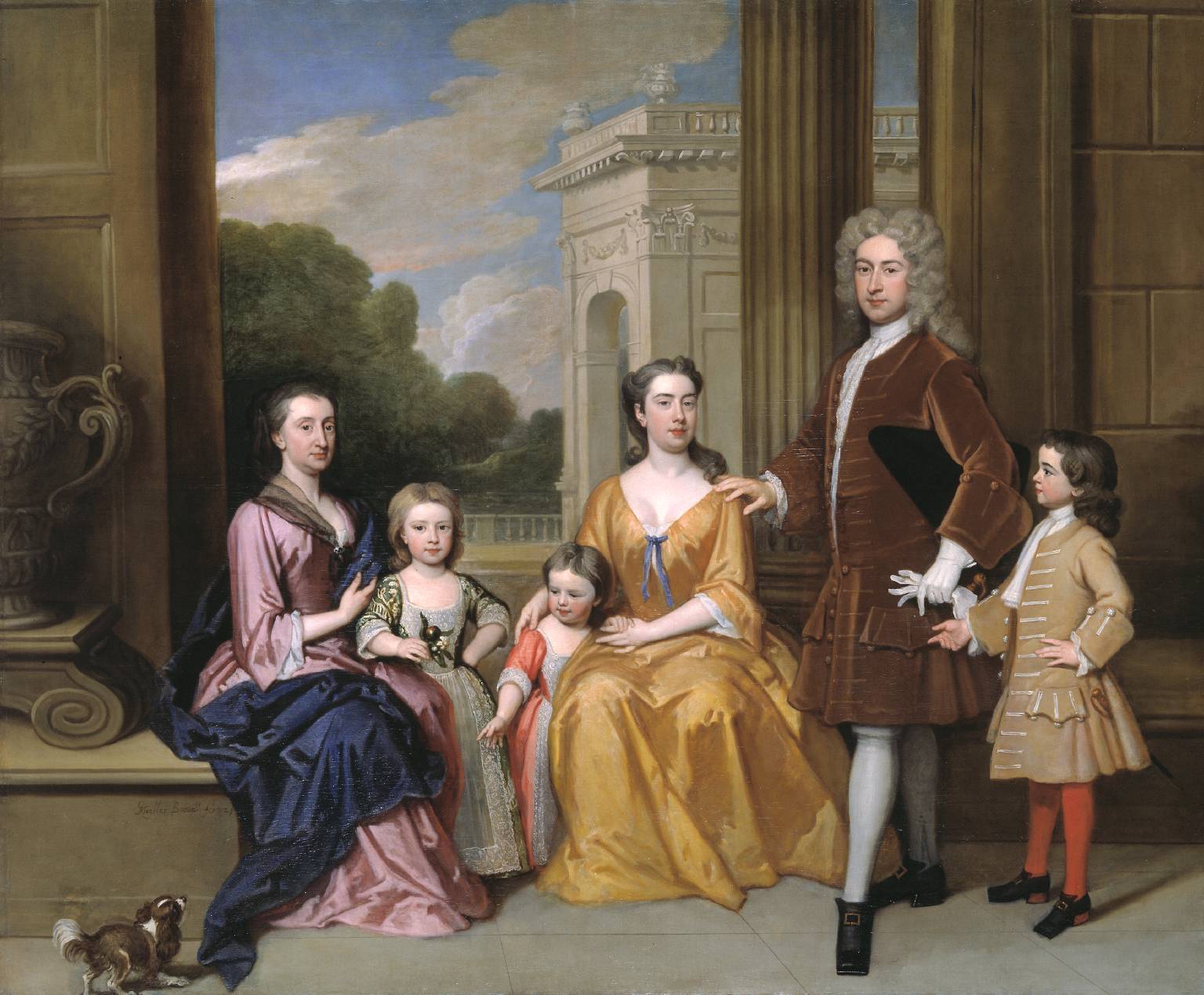

Sir Godfrey Kneller, The Harvey Family 1721

This painting shows the Harvey family of Rolls Park, Essex. Their wealth was built on business, but the scale and format of this picture imitates the aristocratic style of grand courtly portraiture. Does the restrained style of this painting suggest a new set of social values?

Such striking paintings were meant to be seen in country house galleries where other portraits were on show, so that the continuity of the family over generations could be stressed.

Gallery label, March 2011

22/28

artworks in Metropolis

Arthur Devis, Portrait of a Man c.1750

Devis was a native of Preston, Lancashire, but by the early 1740s had moved to London. He took a studio in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, an area much favoured by artists, and by 1750, the most likely date for this portrait, had built up a prosperous business. The identity of this gentleman is not known, although he appears elegantly attired, seated in a bare yet fashionable interior, fingering a letter he has just written. Devis is known to have used studio props for accessories and furniture in his portraits, and to have created imaginary architectural settings, and it could be that this is the case here.

Gallery label, August 2004

23/28

artworks in Metropolis

Samuel Scott, A Morning, with a View of Cuckold’s Point c.1750–60

Cuckold's Point marks a sharp bend on the Thames near the church of St Mary, Rotherhithe. The unusual name came from the post surmounted by a pair of horns, shown by the steps on the right. Horns indicated a cuckold: a man whose wife had cheated on him.

This view and its pair, A Sunset, with a View of Nine Elms, were designed to complement each other by showing river vistas looking west and east. They also show contrasting times of day: Cuckold's Point is seen in a silvery morning light and Nine Elms in an evening glow.

Gallery label, July 2004

24/28

artworks in Metropolis

Joseph Highmore, Mr Oldham and his Guests c.1735–45

This informal group portrait was painted for Nathaniel Oldham, to commemorate a dinner party at this home. Oldham came home from hunting so late that the friends he had invited to dinner ate without him. He found them relaxing with a bowl of hot wine. Oldham is shown on the far left. In the centre, holding a pipe, is a neighbouring farmer. His friend, a local school master, holds a blue and white bowl. Between them, wearing a red velvet cap, is Joseph Highmore himself, Oldham’s close friend who was commissioned to paint the scene.

Gallery label, February 2016

25/28

artworks in Metropolis

Samuel Scott, A Sunset, with a View of Nine Elms c.1750–60

This Thames scene forms a pair with the view of Cuckold’s Point, also on the south bank of the river. Nine Elms is the name given to the area now dominated by the New Covent Garden Market, which is on the opposite bank from Tate Britain, to the west of Vauxhall Bridge.

The view probably shows the Nine Elms pier; the trees in the background are presumably the tall elms that gave the area its name. Scott appears to have taken an interest in the more rural stretches of the Thames after he bought a country retreat at Twickenham in 1749.

Gallery label, July 2004

26/28

artworks in Metropolis

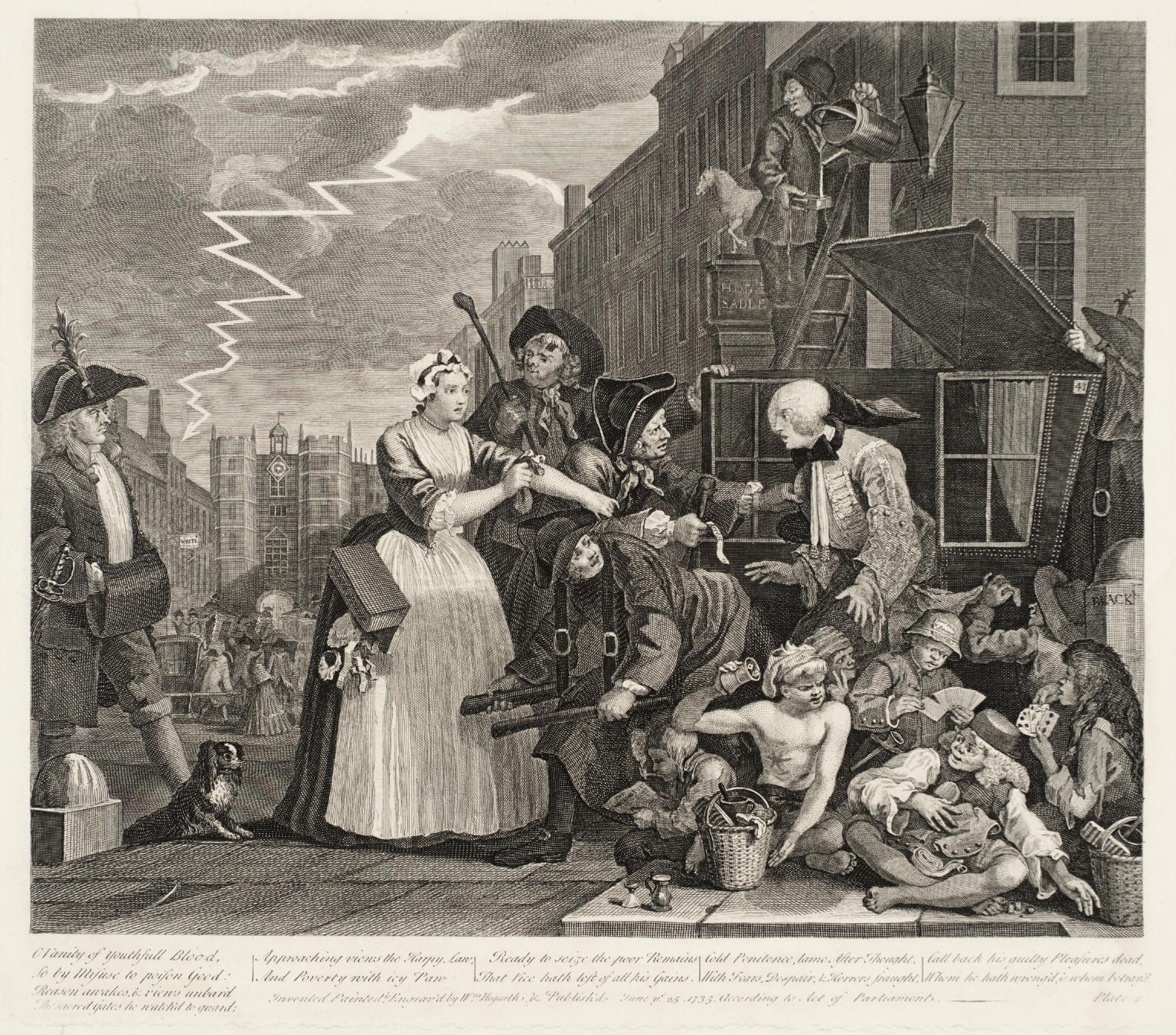

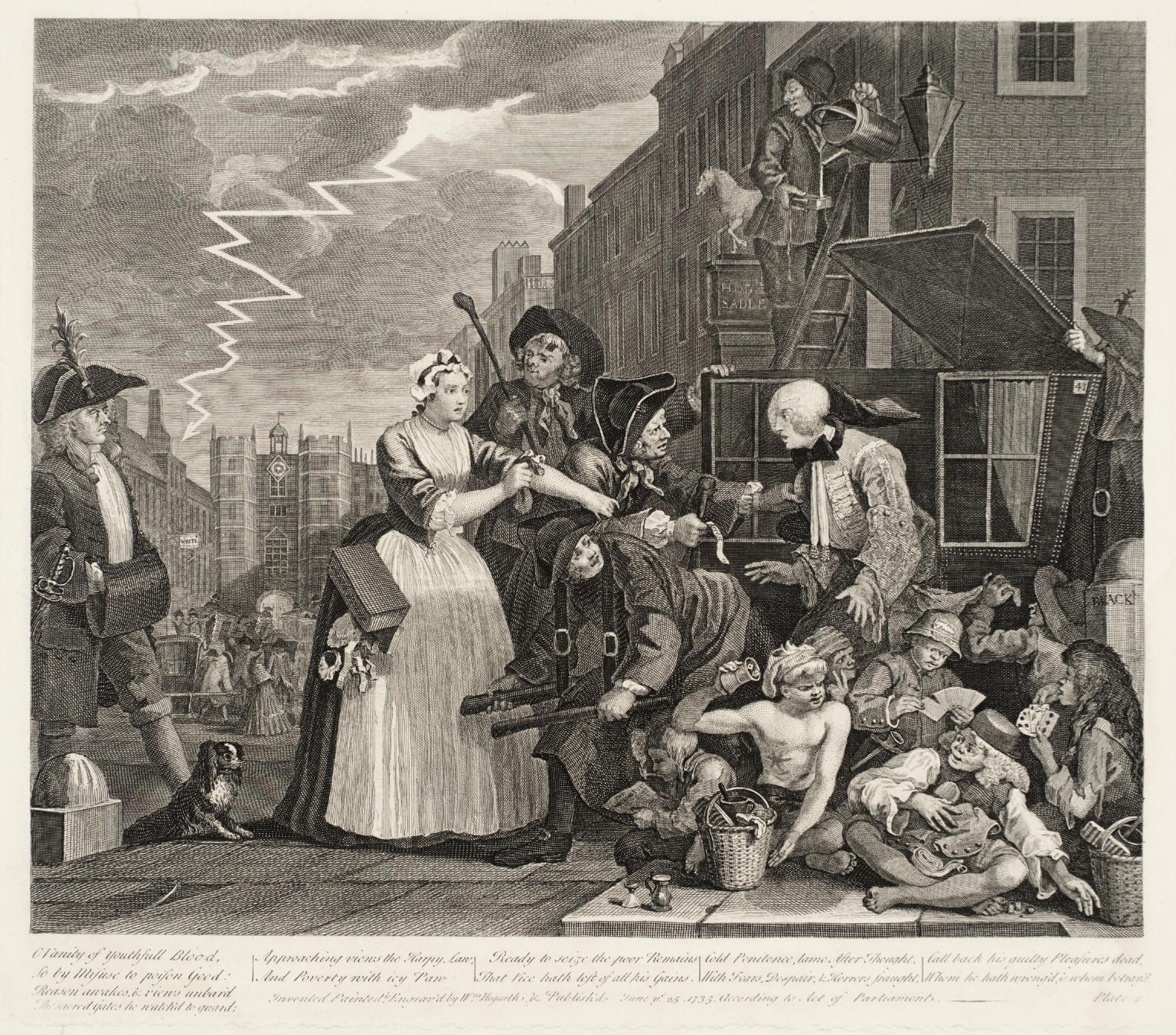

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress (plate 4) 1735

27/28

artworks in Metropolis

Balthazar Nebot, Covent Garden Market 1737

Nebot’s view of Covent Garden looks west towards St Paul’s Church. It records the activities and architecture of Covent Garden which, by the 1730s, was at the heart of London’s artistic community. It was a popular urban subject, also painted by Samuel Scott, among others. The market was first developed in the 1650s. Twenty years later the Earl of Bedford was given permission to ‘hold forever a market in the Piazza on every day in the year except Sundays and Christmas Day for the buying and selling of all manner of fruit, flowers, roots and herbs’.

Gallery label, February 2016

28/28

artworks in Metropolis

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/28 artworks

You've viewed 28/28 artworks

Responses

-

On display at Tate Britain part of Historic and Modern British Art

-

On display at Tate Britain part of Historic and Modern British Art

-

On display at Tate Britain part of Historic and Modern British Art