The research is contextualised within an evolving framework of critical archival theory, drawing from and building upon Hal Foster’s 2004 article ‘An Archival Impulse’.1 In doing so, it seeks to understand how the contemporary art museum might facilitate moments of experimental archival practice.

Introduction

This article presents research undertaken as part of the collaborative research project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, which explores how Tate navigates artworks that challenge the established boundaries between its artworks and archive collections.2 It aims to contextualise the project’s definition of and proposal for the ongoing collection and care of artworks that generate archival material at each activation or display.3 While the paper will touch on several artworks in the Tate’s collection to contextualise the evolution of archival art, the core artworks at the centre of this case study are: Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008 by Tania Bruguera; Film 2000 by Pawel Althamer; The British Library 2014 by Yinka Shonibare; Something Going on Above my Head 1999, by Oswaldo Maciá; ‘The Lunch Triangle’: Pilot work B. Codes and Parameters 1974, by Stephen Willats; and Embassy 2013–ongoing, by Richard Bell.4

This research is informed by my formal training as an archivist, my role as an embedded researcher within the project, and the ways in which I experienced Tate’s archival structures from both an inside and outside perspective. My discussion of these artworks, their archives and the artists’ intentions have been informed by interviews and discussions with artists undertaken either as part of the Reshaping the Collectible project or as part of the acquisition process. I will situate this form of contemporary art practice both within a history of archival artworks and in dialogue with emerging archival theory and practice that rejects neutrality and champions a collaborative, record-creator-centred approach to collecting, cataloguing and providing access to archival material.

I will start by establishing some definitions of archives and ‘the archive’, drawing out the link between memory and labour, and considering different disciplinary definitions and uses. I am interested in how ‘the archive’ as a concept or construct has come to serve as an overarching metaphor for memory, and how an inadvertent erasure of archival labour and expertise can create disciplinary gulfs. The discussion will contextualise the different interpretations of archives at Tate, and the impact these have had on the research in practice.

Throughout the project, Reshaping the Collectible has drawn upon Fernando Dominguez Rubio’s examination of ‘unruly’ objects. He defines such objects as those that ‘operate as vectors of transformation and change within the museum by posing diverse challenges to existing boundaries, by redistributing competencies and expertise, and by creating, in so doing, a new cartography of power within the museum’.5 Artworks that generate archival material have been acquired by Tate without clear protocols, workflows or processes for their care because they have not been recognised as archives according to existing institutional definitions: they are unruly objects. Ideas of the unruly also offer a framework for thinking through what opportunities for change these artworks offer Tate’s wider archival practices.

I will explore artworks that generate archival material through a history of archival art – artworks that call on archival imagery, documentation and information – to demonstrate the parallels between these artworks and evolving archival practice. While drawing on foundational texts about archival art, I will also introduce literature that explores expanded interpretations and definitions of ‘the archive’ and the archival turn.6 Building on Hal Foster’s essay ‘An Archival Impulse’, I will situate these archival artworks within three categories: Deep Storage, the Archival Impulse and Living Archives. Finally, calling on ideas of the unruly, I will discuss how Tate has explored radical, experimental and collaborative archival practices to ensure the ongoing care and collection of artworks that generate archival material.

Artworks that generate archival material: A definition

While each artwork requires different levels of care and stewardship, the following working definition has been produced to identify and understand what is meant by ‘artworks that generate archival material’:

These are artworks that, on the instruction of the artist, or by processes that are inherent to the way the artwork exists, generate additional – usually documentary – material at each activation or display. The artwork creates ‘documents’ intentionally, leaving traces or remains. The generative archive material contextualises the artwork and roots it in the history of its production, exhibition, display and – in some cases – audience interactions. The archive material is typically understood to be a component of the artwork; an output of the way it works, the way it functions, and should not be used in place of the artwork for exhibition.7

The definition is used to determine whether archival material acquired with an artwork is a component of the artwork, and where it should be cared for within the institution. It supports a series of questions added to Tate’s Collection Care pre-acquisition checklist as part of this research.8 In the context of this paper, the definition grounds these artworks within Tate’s production of archives, records and documentation, and their potential for unruliness.

Archival labour and archival fragility

In her 2016 article, ‘“The Archive” is Not An Archives: Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies’, Michelle Caswell writes that scholars working in the humanities have ‘deconstructed, decolonised and queered’ the archive in parallel to the development of key theory and practices by archival scholars.9 The result of these parallel developments sees the two groups – despite discussing similar themes – ‘largely not taking part in the same conversations, not speaking the same conceptual languages’, and therefore not ‘benefiting from each other’s insights’.10 Framing ‘the archive’ as a metaphor for memory neglects to consider the labour of producing and caring for archives, and that archives exist as a contextualised body of material that produces and holds memory. Caswell highlights the importance of archival labour as ‘a prerequisite for making material traces “archival”’. The erasure of archival labour could be considered a form of interdisciplinary failure. These moments of erasure are seen in the lack of references to archival scholarship in influential texts such as Jacques Derrida’s book Archive Fever of 1995; in the conferences about archives in a post-custodian era to which no archival workers are invited to speak;11 and in the semi-regular news articles announcing that a historian has ‘discovered’ a ‘long lost’ item among a fully catalogued and accessible set of records.12

Caswell proposes that a possible reason for this erasure is the ‘construction of archival labor as a feminine service industry’. Like other feminine professions – she cites teaching and nursing – archival workers have been ‘relegated to the realm of practice, their work deskilled, their labor devalued, their experience unacknowledged’.13 Modern archival scholarship, which situates the archivist as an objective, passive, neutral guardian of records, developed within a predominantly white and male workforce.14 In their dedication to objectivity and neutrality, archival scholars wrote themselves, and the mostly female archival workers who came after, out of their own practice. It may be considered a coincidence, but as more women entered the field, archival theory shifted to a more subjective and more politically aware scholarship. Postmodern archival theory, critical archival discourse, trauma-informed practice, community and indigenous archival theory draw heavily from other discourses, including feminism, to inform their research. All these approaches consider the ways in which archival labour, and the people doing it, impacts archival collections, practice, theory and scholarship.

Community archives are collections of material that document a group of people brought together by a collective commonality – be that an identity, location or interest – and produced and maintained by the self-identifying community.15 From an archival literature perspective, it is acknowledged that these are communities that have been excluded from formal archival institutions, and therefore need to document their own experiences and histories. Alex Poole expands on this definition, writing that ‘community archives puncture common misconceptions of archives as objective and neutral; further, they enable the challenging of archives as long-standing bastions of governmental and bureaucratic power, authority, and control’.16 Community archives potentially contain less unique information (a prerequisite in standard archive definitions), and therefore place a heavier reliance on context to build collective, shared, pluralistic memories and identities.

Antonina Lewis has coined the term ‘archival fragility’ to address a widely felt scepticism in the sector to these expanded definitions and interpretations of the archive.17 Lewis writes that archival fragility ‘symptomizes unwillingness or inability on the part of professional archivists to fully recognize and compensate for their complicity in the historicity of the archive’.18 The independent, democratic and grassroots nature of community archives meant that they were often dismissed as ‘ephemeral’ and ‘unarchival’ in archival literature. Lewis writes that rejection from the formal archive provides ‘protection for an inequitable status quo, fortifying the structural forms that continue to enforce the custom of archives (as repositories)’.19 It perpetuates the cycle of exclusion and marginalisation that creates the need for community archives.

One common symptom of archival fragility is to weaponise the fragility of archival material by using the language of survival. Using the example of repatriating archival material from institutions to communities, she writes:

In equating survival with archival preservation, archivists implicitly disparage and depreciate the capabilities of people outside of the profession to preserve records in meaningful ways. The unspoken logic of archival fragility is that the sanctity of the formal archive, premised on deferred access and exemplified by the archival principle of respect des fonds, outweighs violations to living beings.20

This logic states that the material created outside of formal archives is not archival, but the formal archival material cannot be repatriated to the creating communities because they do not know how to care for it. It maintains that the material cannot exist within the archive but could not survive (and holds no legitimacy) outside of it. Lewis summarises this by stating that:

By positioning as threats all challenges to archival language or authority, archivists shift attention away from how people are actually experiencing the archive and centre the form as legitimizing itself: archival authority remains normalized and the “threats” to destabilization remain marginalized.21

Archival fragility reinforces the importance of formal training and professionalisation as the only legitimate form of archival labour. It echoes Caswell’s statement about archival labour making material traces ‘archival’, but perpetuates the violence of neutrality and marginalisation, by accepting gaps and silences as history.

This research prompted several conversations around neutrality and agency in practice in the Tate Archive team. It was decided that the practical work – the care and stewardship of artworks that generate archival material – would be carried out by the conservation department rather than the archive. This was because the archives should be considered components of the artwork.

Tate’s archives: Boundaries between collections

Tate has two archives, which serve distinct purposes. Tate’s institutional archive – referred to as the Public Records Collection – documents the history of Tate and the art collection. Tate Archive, meanwhile, collects material relating to the history of the British art world, including the archives of galleries and artists, critics and collectors who have lived or worked in Britain.

The records of each department’s core activities are placed on deposit as historic records in the Public Records Collection. These records allow Tate to meet its legislative obligations as a Public Records Body and ensure its accountability as a national collection.22 All artworks generate documentation as an outcome of Tate’s stewardship of the work, created through processes such as acquisition, research, loan, display and conservation. These are part of the Public Records Collection as they are the result of museum processes rather than the artwork itself. Artists’ studios and commercial galleries also create archives. These records track the exhibition and display of an artwork, documenting its cultural and economic value over time. These records can also include images of the work, interpretation or press releases. These archives mimic museum documentation and are usually absorbed into conservation’s acquisition records as the artwork comes into the museum.

Tate Archive holds material of a different nature, including artists’ archives. These often contain preparatory, secondary material related to artworks: drawings, photographs or incomplete material produced as a by-product or in preparation for a final artwork. If acquired alongside an artwork, archive material that meets these criteria will usually be separated from the artwork’s museum documentation and acquired into Tate Archive.23

What are the systems of value that define the difference between the artwork and archival material? At Tate, these include the specific criteria and collecting remits of the distinct collections, as well as external factors such as the art market, the requirements of artists or their estates, and the distribution of internal resources. At Tate, the art collection is the priority collection, which affords it the ability, knowledge and resources to care for and display these items as artworks rather than as research material.

The Turner Bequest makes up the majority of Tate’s British collection and is a powerful example of how systems of value affect what is considered artwork, what is considered archival and how they are cared for within the museum. Upon his death in 1851, Turner bequeathed his entire studio to the nation. This included 300 paintings, and ‘approximately 37,000 drawings and watercolours ranging from fully worked-up studies to the scrappiest sheet recalling the briefest touch of the artist’s hand’.24 The entire bequest was acquired into the art collection, including the preparatory drawings and sketchbooks one would expect to find in an artist’s archive. This means the Turner Bequest benefits from the resources and care, including digitisation, assigned to the art collection. By comparison, Tate Archive has a very small budget for conservation work, despite being the most accessible, and most regularly handled, collection at Tate. Turner’s status in British art history dictates the value of this collection and the terms of its care, disrupting the institutional categories that divide art and archive collections.

These boundaries are tested in other ways too. In an art museum, material moves through the collections as its collecting practices evolve. It is not uncommon for items to be acquired into the archive, serving as a ‘placeholder’, when no other collection is able to hold them effectively. One example is Joseph Beuys’s Four Blackboards, which was produced as part of the artwork Information Action for Tate’s 1972 show Seven Exhibitions.25 On 26 February 1972, Beuys delivered a six-and-a-half-hour lecture about his practice and politics in the gallery, alongside videos and other documentation of previous ‘actions’. During this lecture, Beuys produced three blackboards (the fourth was produced at a second lecture held the next day at the Whitechapel Gallery). These blackboards were acquired into the archive in 1972, along with a fifth blackboard. Four of the five were transferred to the main collection in 1983, but the fifth remains in the archive. An accompanying note explains this decision:

As there are only a couple of words/marks in one of the corners, and in all probability the board was erased by Beuys during/after the action, it was decided that this board should be recorded as an archival item; though kept in the Main Store. A photograph of the board has been retained in the Single Item box.26

Four Blackboards was transferred to Tate’s art collection in 1983, in part because blackboards were taking on a new importance in Beuys’s practice. This prompted curators to reappraise their role and value, and the blackboard’s status changed from archival, research objects to works of art. Information Action was documented in a number of ways: the film footage of the event sits within Tate’s Education Collection, while the photographs – although produced as documentation of Tate activities – sit in the Tate Archive rather than in the Public Records Collection. Four Blackboards pushes against many of Tate’s established collection boundaries. Returning to Rubio’s definition of unruly objects, we see how both the Turner Bequest and Beuys’s Information Action ‘pose diverse challenges to existing boundaries’ at Tate.

Unruly Records

This research emerged from a series of questions raised by Tania Bruguera’s performance Tatlin’s Whisper #5, which was acquired in 2008 after its first performance in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall.27 The performance features two mounted policemen who enact a number of crowd control techniques on an unaware audience in the museum or gallery, splitting them into groups and moving them back and forth through the space. The artist contract states that the performance should not be instantly recognisable as an artwork (it cannot be announced or publicised beforehand),28 and aims to invoke in the audience memories of civil unrest. The contract also states that an archive of the work must be created at each activation, however Bruguera uses the words ‘documentation’ and ‘archive’ interchangeably throughout the contract. This slippage between terms – their different meanings applying to different practices in the museum – and the unclear purpose and status of the archive resulted in inaction. As the research progressed, it was discovered that Tate held several other artworks that were acquired alongside Bruguera’s and that also produced archival material, and more were entering the collection. It also became clear that there has been little cross-disciplinary discussion between museum departments. The Tate Archive team, for instance, were not consistently consulted about these artworks and their potential archives. With no clear distinction between archives and ‘the archive’ from the artist’s perspective, archival material languished between collections, unsupported and uncollected.

This inspired several questions: Why might an artwork generate archival material? What was the institution not doing that the artist felt the artwork needed to do instead? Any attempt to answer such questions means seeking a way of managing this archival material outside of the structures and boundaries artists might be pushing against, and understanding how the archival impulse is evolving in contemporary art practice. Could Tate utilise new forms of archival practice to effectively collect, care for and make these archives accessible?

First, it was important to understand what made this material archival. What sets it apart from the documentation that all artworks create as they enter museum collections? These unruly works with their unruly records challenge not only the boundaries between the art collection and the archive, but the status of Tate’s own recordkeeping and documentation practices. I began by considering how evolving collecting practices around performance art has contributed to the blurring of boundaries between documentation (as produced by the artist or an institution) and archive material. Tate has established a framework for collecting and exhibiting performance works that includes curatorial, registrar and conservation teams.

The Tate ‘Art Term’ definition of ‘Performance’ states:

Throughout the twentieth century performance was often seen as a non-traditional way of making art. Live-ness, physical movement and impermanence offered artists alternatives to the static permanence of painting and sculpture.29

Until 2021, the Tate ‘Art Term’ for Archive – which has been updated as part of this project – placed great emphasis on the importance of documentation to ephemeral practices such as performance, land and conceptual art:

The rise of performance art in the twentieth century meant that artists became heavily reliant on documentation as a record of their work. A similar problem arose in relation to the Land art movement of the 1960s whose interventions in the landscape were often eradicated by the elements. Conceptual art often consisted of documentation. In practice the documentation – photograph, video, map, text – was rapidly adapted to have the status of artwork.30

What is performance documentation? Paul Auslander approaches the question from an ontological perspective in his 2006 article ‘The Performativity of Performance Documentation’.31 He divided performance documentation into two categories: ‘documentary’ and ‘theatrical’. ‘Documentary’ is evidence that the performance happened. This is the material that conservation would create for their records of a performance over its lifetime, it can be used to inform reconstruction or reperformance. ‘Theatrical’ refers to performance produced for the camera and is a type of artwork itself. Auslander cites Cindy Sherman’s photographs and Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void 1960 as examples. The documentation is not for evidentiary purposes in this case, but rather becomes the artwork.

‘Documentary’ documentation is produced in two contexts: by the artist (before acquisition) and by the institution (post-acquisition, where it is known as collection documentation). Both are produced as a record of the performance, as evidence and for contextualisation and explanation. Artists need to produce an image of the work, for sales, reproduction and to provide ‘access to the originary event’.32 However, only the ‘documentary’ documentation produced intentionally by an artist (or with their authorisation) can sit in place of the performance as the artwork. ‘Documentary’ works in Tate’s collection – videos and photographs of performances – include pieces by Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Mona Hatoum, Rebecca Horn, Gilbert & George and Yoko Ono. However, since institutions have expanded their collecting practices to acquire the performance itself (since 2005 at Tate), artist-produced documentation no longer needs to serve as an artwork ‘placeholder’.33 It can return to being documentation. This can either be absorbed into the conservation documentation upon acquisition or stay with the artist as an archival record.

Collection documentation is a record. Records comprise archives. At Tate, the Time-based Media Conservation team creates performance documentation as a record of the event, how it was re-performed and staged and who was involved. Tate’s institutional records follow a ‘lifecycle’ model which sees records appraised and transferred to the Public Records Collection when the records are deemed no longer useful for current institutional activities.34 Unlike other institutional records, conservation documentation does not reach the end of its ‘lifecycle’, but remains active. They may never make it to the archive, but they still have archival value.35 In records management theory, this would be regarded as following what is known as the ‘records continuum’. These records, while remaining in use, are still subject to the Freedom of Information Act and can be accessed for research purposes on request.36

Artworks that generate archival material can mimic conservation documentation (and artist’s ‘documentary’ documentation), and this multiplicity makes such material unruly. This ‘unruliness’ demonstrates why these archives had not been proactively collected, and how this work slipped between institutional practices. They push up against existing, established boundaries, definitions and expertise, and in doing so require new forms of collection and stewardship.

The archival turn

Artworks that generate archival material not only blur the boundaries between artwork and archive, but challenge the archival and museological methodologies used to uphold them. In this project, such methodologies have been considered in dialogue with critical archival theory. This approach has presented opportunities for interdisciplinary practice that places archival labour – collecting, contextualising and providing access – at the centre of recognising and defining artworks that generate archival material.

Critical archival studies includes conceptions of ‘the archive’ that have emerged in other disciplines, including from feminist, queer and decolonial theories. In her article ‘Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines’, Marlene Manoff introduces the archival turn and its impact on archival theory and practice:

For those interested in pursuing theoretical work, archival discourse provides a place to enter the debate about changes in knowledge-making practices. Librarians and archivists are intimately aware of how new modes of scholarly production and communication are transforming the ways we collect, organize, preserve, and provide access to the archive.37

Manoff argues that archives – what is and is not selected – are inherently political, and never neutral, and therefore demonstrate an explicit relationship between information and power. While Manoff acknowledges the influence of other scholarly archival turns on archival theory, she writes that: ‘These fields, in turn, would be enriched by the perspective of librarians and archivists working inside the archive and who thus occupy a privileged terrain from which to address these questions.’38 Like Caswell, Manoff argues that the failure to acknowledge archival studies as a distinct discipline with its own theory and practice, or what it means to undertake archival research potentially limits the impact of the questions they are asking and answering of the archive and archives.

Jacques Derrida’s 1995 book Archive Fever established the idea that anything can hold a memory, and therefore anything can become an archive. Subtitled ‘A Freudian Impression’, the book considers the archive in relation to Sigmund Freud’s conception of the death drive, the human desire to collect and store memory. Derrida extends the inextricable link between memory and identity, giving it physical form in the archive. Manoff identifies the ways in which Derrida’s text relates to archival labour:

One of Derrida’s most valuable contributions is his elaboration of the notion that the structure of the archive determines what can be archived and that history and memory are shaped by the technical methods of what he calls ‘archivization’[…] The methods for transmitting information shape the nature of the knowledge that can be produced. Library and archival technology determine what can be archived and therefore what can be studied. Thus Derrida claims ‘archivization produces as much as it records the event’.39

Archive Fever was a contributing factor in archival practice’s postmodern paradigm shift, in which archivists rejected ideas of objective neutrality, and acknowledged the archive as a system of power inextricably linked with societal identity.40 Derrida’s conceptualisation of the archive as a metaphor for memory – linking collecting and storing, memory and identity, power and marginalisation – is a driving force of contemporary art’s archival turn.

The archivist Kathy Carbone describes some of the tactics employed by artists who use archival motifs. These artists ‘invent or fabricate archival materials or an archive itself to question absences, expose missing or silenced voices, or address gaps in institutional archives and collective history – bringing attention to the fragmentary and incomplete nature of archives’.41 She goes on to explore how artists use new models of post-custodial, community and participatory practices to redress the power and silences of the archive.42

Artists apply a variety of critical and aesthetic approaches to the archive, and their archival interventions are often concerned with constructions of meaning, challenging or provoking change in a situation or condition, opening out possibilities for new meaning-making processes, and providing alternative and more socially situated meanings that diverge from an ‘official’ interpretation.43

The archival turn in contemporary art echoes the evolution of archival theory and practice.44 Returning briefly to Marlene Manoff, who references how the different investigations of the archive have blurred the boundaries between libraries, archives and museums as heritage or memory institutions, contemporary art can exist within institutions that contain all three practices in one place. These archival artworks trouble the established museological boundaries and collections.

The evolution of archival art

In order to contextualise the archival turn at Tate, I have considered archival artworks in three categories: Deep Storage, The Archival Impulse and The Living Archive. Each is informed by key literature that builds on the existing art historical canon, prompted in part by archival turns in other disciplines. The intention is to find ways to address the archival turn in contemporary art within Tate’s collection and museum practices, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and exchange.

> First category: Deep Storage

The artworks in this category investigate the interiors of archives and museums as memory institutions. They may be images of storerooms, archival stacks, rows of boxes or glimpses behind the scenes of the institution. They often subvert the role or expectations of the audience. They explore order and collecting in relation to the human desire for knowledge and discovery. The category takes its name from the exhibition Deep Storage: Collecting, Storing and Archiving in Art, held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1998. Curated by Ingrid Schaffner, the exhibition explored how ‘personal obsessions sustain collecting impulses that give way to assemblage by way of the archive’.45 The catalogue essay describes how this collecting impulse is tied to questions of anxiety, power and historicisation:

Anxiety and dust provoke the archiving impulse. In the museum – the mausoleum most artists still aim to enter through their work – the recesses of the storeroom simultaneously beckon and bar access to history. Art that assumes the storeroom’s cladding and demeanor displays a desire to repose within the museum’s collection.46

Fig.1

Louise Lawler

Given by the Widow 1993

© Louise Lawler

Tate

Fig.2

Louise Lawler

Splash 2006 printed 2012

© Louise Lawler

Tate

Several exhibitions in the late 1980s and 1990s, including Deep Storage, established a form of art- and exhibition-making that visually perform museum and archival practices: collecting, cataloguing, interpretation, preservation and providing access.47 There are several examples of works in the Tate collection that sit within the Deep Storage category. A number of photographs by Louise Lawler (figs.1 and 2) capture the hidden or behind-the-scenes spaces of museums, such as storerooms, curators’ offices and conservation studios. These photographs give the audience direct access to these inaccessible spaces, questioning how the context in which a work is seen affects its interpretation. Schaffner writes that Lawler ‘haunts’ these spaces.48

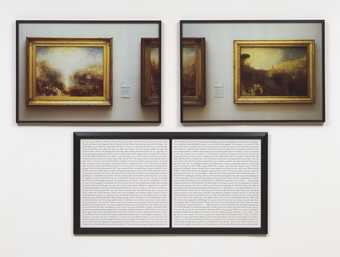

Fig.3

Sophie Calle

Purloined (Turner) 1998–2013

© Sophie Calle

Tate

In Sophie Calle’s series ‘Purloined’, photographs of stolen artworks are displayed alongside interviews with curators, guards and other museum staff about their relationships with the stolen pieces (fig.3 and Purloined (Lucian Freud, Portrait of Francis Bacon), both 1998–2013). The work is an extension of Last Seen..., an earlier series by Calle inspired by the theft of thirteen artworks at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, in 1990. Following the wish of the museum’s benefactor for the museum to remain as she had left it, the empty frames were left in place after the heist.49 Calle’s wider practice is a voyeuristic documentation of private experiences – both her own and her subjects. In this series, by documenting museum practices and the value of its collection, she takes her own archival impulses and turns them towards the museum.

Artworks in the Deep Storage category do not act as archives, but do explore themes of power, knowledge and counter-narratives. These artworks might be considered passively archival, or documentary, but lay the foundations for more explicitly archival artworks.

> Second category: The Archival Impulse

Despite not looking like archives – there are no boxes or vitrines of material in the examples at Tate – the artworks within the Archival Impulse category perform the archive. They perform archives as memory, often in non-linear and dialogical ways. The category takes its name from Hal Foster’s essay ‘An Archival Impulse’, which presents ‘the archive’ as a lens through which to explore what it means to collect and produce memories and their inherent connection to one’s own and a collective identity. He defines the archival impulse as the intention ‘to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present’. The artworks he uses to illustrate this impulse, including work by Tacita Dean, Sam Durant and Thomas Hirschhorn, are sometimes ‘drawn from the archives of mass culture, to ensure a legibility that can then be disturbed or detourne; but they can also be obscure’.50 These artworks may not look like archives, but they create counter-narratives, which Foster considers archival. While he makes no reference to archival labour, Foster offers a nuanced exploration of archival politics: who gets to tell history and who does not; why this lost historical information appeals; and how archival practice navigates the potentiality of loss.

At Tate, there are artworks that produce counter-narratives or call on lost or displaced historical information and offer alternative narratives in their documentary approach to these topics. Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photographs of water towers (Water Towers 1972–2009) pre-emptively created an architectural archive. Sophie Calle’s The Hotel 1981 is a series of photographs documenting various hotel rooms in a Venetian hotel at which Calle worked as a chambermaid. The photographs are exhibited alongside her diary entries which document the content of the rooms and suitcases, which beds had been slept in, and transcriptions of the occupants’ correspondence. Calle’s archive forces a narrative ‘observed through details lives which remained unknown to me’.51 Susan Hiller’s Dedicated to the Unknown Artists 1972–76 contextualises and gives a narrative to these commonplace objects via what she described as a ‘methodical-methodological approach’.52 Hiller’s narratives are not concerned with fact, knowing that the archive does not – and cannot – contain an objective truth.

Tate’s collection also includes artworks that meet Foster’s definition of the archival impulse but also look and feel archival. These artworks might consist of archival footage, vitrines of press cuttings, leaflets, writings and photographs. Because they perform, rather than function as archives, they remain artworks. One early example in the collection is The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even (The Green Box) 1934, part of Marcel Duchamp’s ‘portable museum’ series La Boîte-en-valise. Tate’s version is a collection of 94 documents – preparatory drawings, notes, sketches that support the thinking behind his sculpture The Large Glass. These documents are preparatory drawings, notes and sketches, the type of material that Tate Archive lists in its collecting remit. In Mark Dion’s Tate Thames Dig 1999, the artist and a team of volunteers dug up archaeological material from the riverbed of the Thames, close to the sites of Tate Britain and Tate Modern. Re-categorised and presented in vitrines, the material was given a different status, evoking memories of old libraries and archives and for some, cabinets of curiosities.

Fig.4

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum 1991–6

© Susan Hiller

Tate

Inspired by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s collection of art and artefacts, Susan Hiller’s From the Freud Museum 1991–6 (fig.4) serves ‘as an index to the version of Western Civilization that he was claiming’.53 The display is another example of Foster’s ’counter memory and alternative knowledge’. By filling the archival boxes with talismans, souvenirs and fragments of her own collections, Hiller illustrates the slippage between interpretation and expectation, and of personal experience versus the archival experience. It also echoes Kathy Carbone’s questioning of absences in collective history. From the Freud Museum draws attention to the gaps in archives, but also the slippage in one’s own memory.

The Archival Impulse category is also influenced by Okwui Enwezor’s exhibition Archive Fever, which took Derrida’s book as the title for an exhibition on ‘uses of the document in contemporary art’ at the International Centre of Photography, New York, in 2008. Enwezor writes in the preface to the accompanying catalogue:

Archive Fever explores the ways in which artists have appropriated, interpreted, reconfigured, and interrogated archival structures and archival materials. The principal vehicles of these artistic practices – photography and film – are also preeminent forms of archival material.54

The exhibition showcased artists who use archival documents to produce counter-narratives and new archival forms. Enwezor echoes Derrida in his reiteration of the link between memory and identity, writing that ‘the photograph becomes the sovereign analogue of identity, memory and history, joining past and present’, the photograph becomes ‘an anthropological artifact and the authority of a social instrument’.55 Many of these works explore historic trauma – personal and public – to construct archives that reduce the risk of forgetting and therefore of re-traumatising. The artworks categorised as having an Archival Impulse often critique the institutionalisation of only certain types of knowledge and memory. The questioning of dominant forms of memory and narratives seen in these artworks mimics the changing role of the archive (and the archivist) in wider society and its own unfolding practice and theory.

At Tate, we see examples of archival footage and documents used as a metaphor for memory in John Akomfrah’s video works (including those he made with the Black Audio Film Collective), and particularly in his three-screen video work The Unfinished Conversation 2012. This non-linear interrogation of race and identity is told through – and in collaboration with – the archives of cultural theorist Stuart Hall (1932–2014). By building on themes of memory and identity using existing archival material, Akomfrah (and Hall) use the archive as a tool to explore Hall‘s rigorous and constant reappraisal of his own identity throughout his life.

Fig.5

Walid Raad, The Atlas Group

My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines 2000–3

© Atlas Group and Walid Raad, courtesy of Anthony Reynolds Gallery

Tate

My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines 2000–03 (fig.5) is part of a larger body of work by The Atlas Group, a fictional collective established by the artist Walid Raad. The Atlas Group archive is a collection of documents, records and other material from different sources across Beirut. It is a ’contemporary history of Lebanon, with particular emphasis on the Lebanese wars of 1975 to 1990’.56 My Neck is Thinner than a Hair takes the form of 100 framed prints, each containing a photograph of the aftermath of a car bomb, and the scanned reverse of the photograph which include handwritten or stamped notes. The writer Shang Salah has discussed how the artwork brought her an ’affinity with these reclaimed archives’.57 Through Raad’s work, the author reflects on her Kurdistan Iraqi heritage, and how museums and archives – institutions that build our collective memory – have been continuously looted due to ongoing conflict and war.

People’s perception of history is not based on facts or objective truths but rather discontinuous and inconclusive narrations, built on personal interpretations of witnessed events... [Raad] takes it upon himself to collect images and ask questions, holding on to information that would otherwise be lost.58

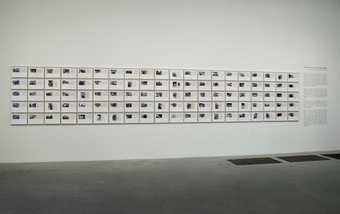

Fig.6

Jeremy Deller

The Battle of Orgreave Archive (An Injury to One is an Injury to All) 2001

© Jeremy Deller

Commissioned and produced by Artangel

Tate

Another work that falls into the Archival Impulse category is The Battle of Orgreave Archive (An Injury to One is an Injury to All) 2001 by Jeremy Deller (fig.6). It is an installation of archival documents and relics pieced together by Deller during the production of his performative re-enactment of the clashes between striking miners and police in Yorkshire in 1984.59 The archive collected material from all sides of the ‘battle’ and includes union badges, police riot training documents, political memoirs and books about the miners’ strikes. He moves from the use of archival material to creation, in what could be considered an attempt to redress the narratives around the miners’ strikes. It also includes annotated material from the re-enactment, thus producing its own archive.60 The Battle of Orgreave Archive blurs the boundaries between the archive’s ‘status as objective documents on the one hand, and historical relics on the other.’61 It archive brings together an alternative history of the clashes, separate from those held by the Home Office, the Sheffield City Archives and the Working Class Movement Library. It is one where both the miners and the police are represented (via National Union of Mineworker pamphlets and a video entitled Police Riot Training) but through the lens of an artwork.

From an archival perspective, artworks such as From the Freud Museum, My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines and The Battle of Orgreave Archive present challenges. When acquired into the art collection, the archival potential of the material – to make such material readily available for research and interpretation – is not met.

> Living Archives (artworks that generate archival material)

The third category of artworks, Living Archives, also address issues of alternative knowledge and counter memory, but function differently from those addressed in the first two categories. These works address marginalisation and archival silences, carving out space in the institution for voices left out of traditional archival institutions and narratives by actively creating new archives. This material should be treated as an archive and not only as an artwork; it should be appraised, catalogued and made available for research. To do this requires new forms of collaborative, interdisciplinary practice in the contemporary art museum.

In archival literature, living archives are those that continue to expand and generate new archives, continuing to build the link between archives, memory and identity. Archivist Eric Ketelaar writes that ‘archives are never closed and never complete: every individual and every generation are allowed their own interpretation of the archive, to reinvent and to reconstruct its view on and narrative of the past’.62 A living archive, he continues, is one that continues to be ‘challenged, contested and expanded’.63 Living archives are those most closely linked with and used by living, breathing communities, and hold their memories, experiences and shared identities. This reiterates that memory, and its role in identity making, is not passive but an active, legitimising tool focused on the agency of those held within these archives.

In ‘Constituting an Archive’, Stuart Hall also speaks to the idea of a living archive. He writes that living is ‘continuing, unfinished, open-ended’.64 For Hall, the living archive and ‘the new work which comes to constitute significant additions to the archive will not be the same as that which was produced earlier, but it will be related to that body of work, if only in terms of how it inflects or departs from it’. What constitutes an archive ‘occurs at the moment when a relatively random collection of work, whose movement appears simply to be propelled from one creative production to the next, is at the point of becoming something more ordered and considered: an object of reflection and debate.’65 Hall uses language of action: ‘movement’ and ‘propel’. Each artwork that generates archival material uses people to propel itself forward, and the artwork’s connection to people will outlive the artist (and the institution as encountered in this moment). There is an infiniteness to this intention to generate archival material and in doing so it creates something so inherently tied to those activations, moments and people.

The artworks categorised as Living Archives are not looking to ‘the archive’ (as a metaphor), but to archives (as repositories of documents). The material is archival, not only because the artist determines it to be so, but because it holds the history of these artworks, its connection to its own past, and records the contributions of the audience and participants. Living Archives sustain the artwork’s connection to the histories, knowledge and narrative it is addressing. This is why a critical archival framework – one that recentres the record creator and how they produce, use and define archival material – has been used to underpin this research. It is for those who create this material to decide if it is archival or not.

> Artworks that generate archival material: Some examples

So far, six works in the Tate collection have been identified as artworks that generate archival material.66 Each requires different forms of care, but through this research some key similarities and identifiers have been noted to guide the ongoing acquisition and care of such works. Artworks that generate archival material appear to be concerned with the historical impetus of their performance or display: why, when and where the artwork is being reperformed or exhibited, and for who. While artworks in the Deep Storage or Archival Impulse categories take the archive as subject, artworks that generate archival material produce an archive to address issues of marginalisation, missed narratives and archival silences. The archive is part of how the artwork operates and unfolds.

Fig.7

Tania Bruguera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008

© Tania Bruguera

Tate

In Tatlin’s Whisper #5 (fig.7), Tania Bruguera meant to invoke associations of civil unrest through the performance of mounted police officers, which she advised should be presented at times of political disturbance.67 The contract stipulates that the ‘owning institution’ (Tate) should create an archive of documentation containing, but not limited to ‘reactions on the piece, critical as well as explanatory materials and future clarifications of the instructions’ and ‘any resulting reference to the piece (texts, reviews, interviews etc)’ each time the work is activated, including during loans.68 Bruguera uses ‘documentation’ and ‘archive’ interchangeably throughout the contract.

It might be argued that Bruguera’s stipulation for a more thorough and expanded form of documentation is linked to the potential change in status of artist-approved or produced documentation that occurred when museums became able to collect performance as live works. Tatlin’s Whisper #5 not only challenges the institution’s ability to collect and document performance artworks, but the stipulation for an archive also challenges the voice and authority of conservation documentation as an institutional record. The documentation – which exists in a constant state of becoming as ‘current records’ – must perform not only as an archive, but also, in seeking externally produced reviews, interpretation and texts, to make space for other voices within it.

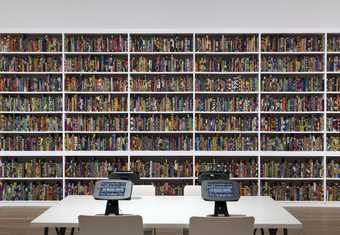

Fig.8

Yinka Shonibare

The British Library 2014

© Yinka Shonibare

Co-commissioned by HOUSE 2014 and Brighton Festival

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Tate

The British Library 2014 (fig.8) is an installation by Yinka Shonibare of 2,700 books wrapped in ‘Dutch wax-print’ fabric, bearing the names of first- or second-generation British immigrants who have made a contribution to British history and culture. Part of the artwork is a website which can be accessed in the galleries or online that invites audiences to submit their own experiences of immigration, a selection of which are then made available on the website for the duration of the display.69 The website submissions are archived each time the artwork is displayed, creating a rich time capsule which documents the atmosphere in which the work was exhibited, and contextualises the work within an ongoing British history.

Fig.9

Richard Bell

Embassy 2013–ongoing

© Richard Bell

Richard Bell’s Embassy 2013 (fig.9), is a joint acquisition between Tate and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, and comprises a military-style tent, a banner and a series of protest placards. It is inspired by the Aboriginal Embassy tent which activists pitched outside Parliament House in Canberra in 1972, in an act of protest for Aboriginal land rights. Versions still stand across Australia as a representation of the struggle for Aboriginal rights and Indigenous politics.70 The space inside the tent is intended to exist as a sovereign space, used as a public forum to host performances, dialogues, workshops and screenings by local activist groups. All programming is documented and added to the archive. This includes videos of discussions and copies of material produced by the activists occupying the tent. Bell requests that any documentation produced be a collaborative endeavour, that the voices of those activating the tent are represented in ‘an archive of solidarity and resistance that transcends national borders’,71 one that contextualises the past, present and future of the work.72

Seeking Solutions

How do artworks that generate archival material challenge the existing boundaries at Tate? Tate Archive’s collecting remit is focused on British artists and institutions, and those who have lived and worked in Britain. There are exceptions to this rule, and the archive will accept the archives of international artists with artworks in the main collection, or archival material attached to specific artworks in the collection. As these expanded forms of history-making are generated by the artwork, it makes them part of the work itself. Coupled with the current limitations in establishing and maintaining links between the archive and the art collection, this means they need to be treated and conserved as components of the artwork.

At Tate, this work is the responsibility of the Conservation department. This meant, however, that the Conservation department at Tate – which is split into specialised teams dedicated to paper, sculpture and time-based media – needed to establish a framework for the ongoing management of this generated archival material as archives. The working proposal for this work has been published as part of this research. It outlines the principles and practices for the care and stewardship of artworks that generate archival material including how to catalogue and make the material accessible within the existing collection management systems at Tate. It also outlines what archive material exists, or has the potential to exist, for each of the six artworks.73

The question then becomes: How can Tate extend this practical stewardship work to make space for a model of critical, participatory, responsive archiving within Conservation to hold these living archives effectively and in line with their intentions?

Slow archiving

One solution is to slow down. This idea has already infiltrated museums via the theory of ‘slow curating’, which Megan Johnston describes as the next wave in museology’s ‘social turn’. She states that in ‘responding to the changing nuances of art practice, communitarian discourse, and the politics of contemporary society; the question of knowledge production comes to the fore – for artists and audiences’.74 To comprehend and make explicit – internally and externally – this knowledge production, museums must slow down. Slow curating is a practice that ‘enables, explores, and expands museum and exhibition experiences for more relevant audience engagement’.75 At Tate Liverpool and Tate Modern this community focused engagement was explored through Tate Exchange (2016–21), a programme dedicated to exploring where art and society meet.76 Slow archiving is concerned with similar questions of knowledge production, but finds its roots in indigenous archival practices, critical archival studies and practices of decolonisation. It involves examining the power structures at play in the archive, questioning who has been centred and why to make changes to the existing parameters and develop reparative and ethical practices.

In their article ‘Towards Slow Archives’, Kimberly Christen and Jane Anderson introduce slow archiving as the re-examination of knowledge production – what has been centred and why – which is then challenged and rectified through collaborative and participatory processes.

Slowing down creates a necessary space for emphasizing how knowledge is produced, circulated, contextualised and exchanged through a series of relationships. Slowing down is about focusing differently, listening carefully, and acting ethically. It opens the possibility of seeing the intricate web of relationships formed and forged through attention to collaborative curation processes that do not default to normative structures of attribution, access or scale.77

The article uses this concept to discuss the return of a number of digitised wax cylinder recordings to the Passamaquoddy people, and the collaborative, participatory, digital archive that the community has subsequently produced.78 As the cultural authorities of this material, Christen and Anderson argue, only the Passamaquoddy people can contextualise this material. The process of archiving this material as a community also becomes a way for them to connect with both their ancestors’ past and their future. The physical cylinders were not repatriated and remain with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography at Harvard University, where they are attributed to a certain ‘Jesse Walter Fewkes’.79 The digitised version in the Passamaquoddy People archives is an authentic representation of how knowledge is produced, held and passed through a community.

Archives were originally established as records of government; the inextricable link to power extends from this formation within state authority and governmental taxonomies. By recentring the record creators or subjects in the catalogue these archives actively fight against the colonial structures of their foundation. As a museum, Tate has made a commitment to explore decolonising practices and address the implicit boundaries that have been built within the museum to ‘accommodate multiple and provisional interpretations’ of the collections. Projects include Provisional Semantics (2020–22) as part of the Towards a National Collection initiative.80

Conclusion

What did slowing down look like at Tate? Change does not happen quickly, and in this respect museums are already very slow places. Furthermore, slowness can be interpreted as a resistance to change, which can often relate to balancing resources, workload and priorities. In practice, it took a long time to put together a proposal for the ongoing care of artworks that generate archival material. It required an examination of the types of archival artworks at Tate, to contemplate their similarities and points of difference and identify the stages of the acquisition process, including where communication could be strengthened. It required examining existing workflows to understand where the care and stewardship of this generated archival material could fit without having to drastically alter the process. It took extensive conversations with stakeholders across the institution, including with colleagues in Conservation, Archive and Records Management, Curatorial and Research. Conservation documentation was crucial for understanding how these archives have been broached with artists during acquisition and reactivations. The artist interviews could be considered the first point in participatory record-keeping, as they are produced with the artists with the mutual aim of understanding and evidencing the ongoing care of these artworks.

Through this process, a definition and means for identifying artworks that generate archival material has been developed. This, in turn, provided our starting point for a proposal and methodology for ways to collect, archive, catalogue and make available for research this generative archival material in a way that acknowledges and honours the collections as living archives. This is still unfolding, being tested and revised. Each of the six identified artworks (and future acquisitions) will require different levels of participation and collaboration, but it has been established that the care and management of these archives will be the responsibility of the Time-based Media Conservation team, with input and guidance from an archival worker.

Where Hirschhorn and Dean focus on memory as an archival trace in the Archival Impulse category, Bell, Shonibare and Bruguera actively create new archives, addressing missed narratives and empty archives. They also speak to the archive as a metaphor for collective memory, power and identity, acknowledging that both using and creating archives are political acts. These artworks bring audiences and communities into the institution and inspire change in Tate’s record-keeping practices. Documentation in the contemporary art museum is an archival record, and if the artist wishes to refer to this material as an archive and use performance documentation as a foundation for building this archive, it is the duty of the museum to ensure that all elements of the artwork are collected, managed and exhibited in line with those intentions. Stuart Hall concludes ‘Constituting an Archive’ with the following:

The activity of ‘archiving’ is thus always a critical one, since archives are in part constituted within the lines of force of cultural power and authority; always one open to the futurity and contingency – the relative autonomy – of artistic practice; [...] an engagement, an interruption in a settled field, which is to enter critically into existing configurations to re-open the closed structures into which they have ossified.81

Defining these generated archives might be seen as putting in place the boundaries and parameters that artists are trying to challenge, potentially perpetuating colonial narratives of order and categorisation that do not and cannot serve all forms of knowledge creation, documentation and experience sharing. However, I appreciate that in order to care for these works effectively, Tate must direct them to the correct practice within the gallery. While institutional structures cannot always be fought against, by working collaboratively they can be expanded, questioned and changed instead, making space for living archives and slow, reparative practices.