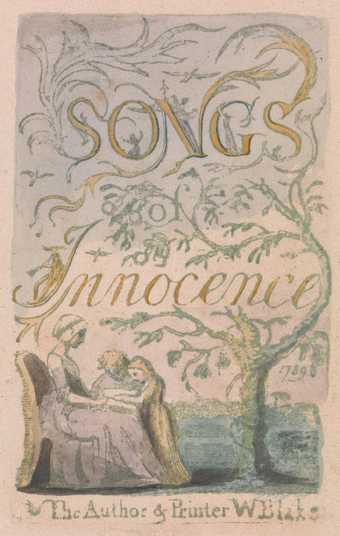

William Blake Songs of Innocence title page 1789

Copy F, plate 2

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

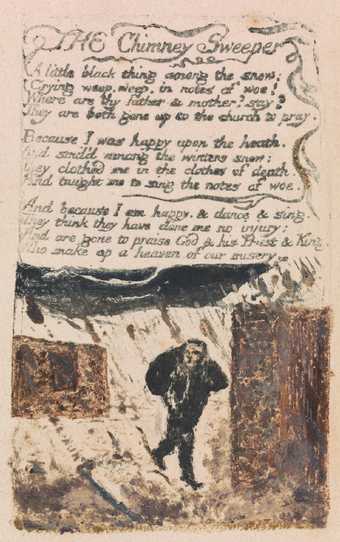

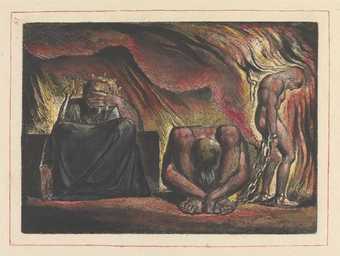

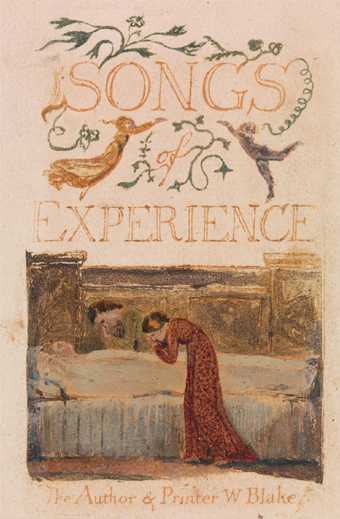

William Blake Songs of Experience title page 1794

Copy F, plate 33

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

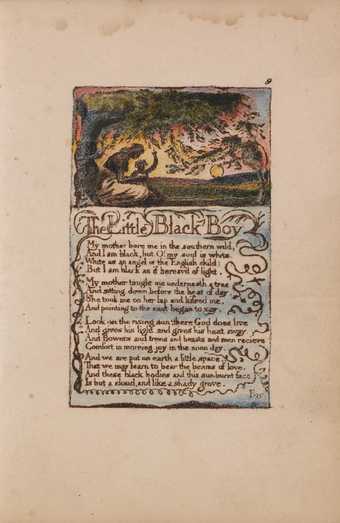

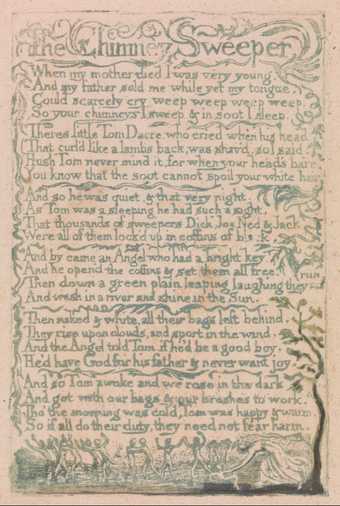

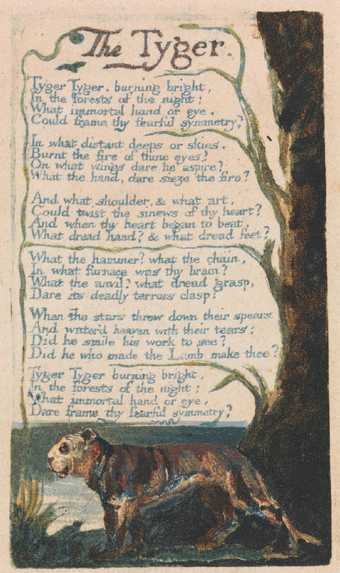

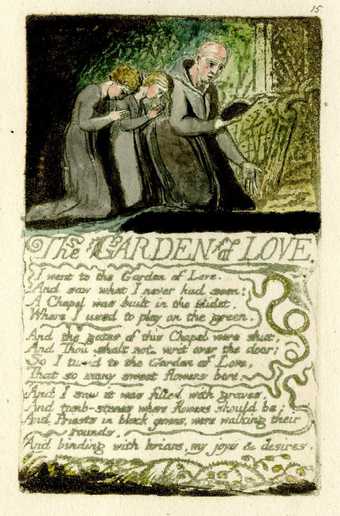

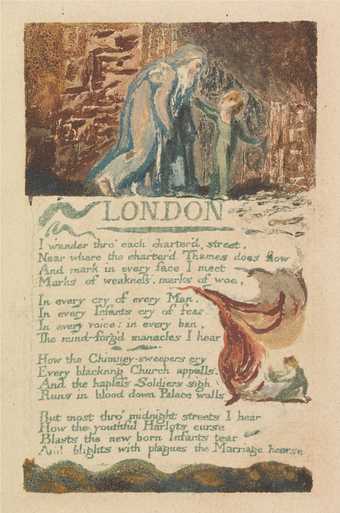

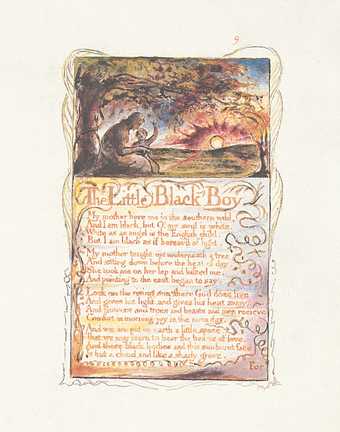

The Songs of Innocence were published by Blake in 1789, and he produced a combined version of Songs of Innocence and of Experience in 1794. The Songs are now often studied for their literary merit alone, but they were originally produced as illuminated books, engraved, hand-printed, and coloured by Blake himself.

The text of the poem and the accompanying illustration formed an integrated whole, each adding meaning to the other. Read highlights from the Songs of Innocence and of Experience in their original illustrated form, and look learn more through summaries and analyses of each poem.

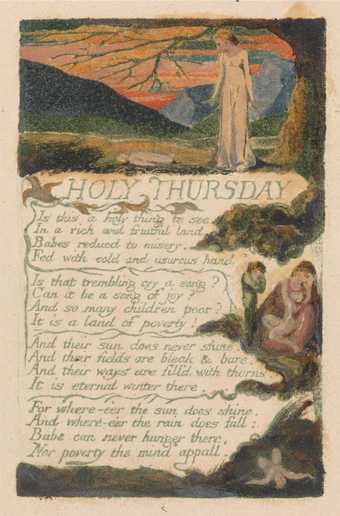

Songs of Innocence: Holy Thursday

William Blake, Songs of Innocence, Holy Thursday 1789–1794

Copy L, plate 10

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Twas on a Holy Thursday, their innocent faces clean,

The children walking two and two, in red and blue and green,

Grey headed beadles walk’d before, with wands as white as snow,

Till into the high dome of Paul’s they like Thames’ waters flow.

Oh what a multitude they seem’d, these flowers of London town!

Seated in companies they sit with radiance all their own.

The hum of multitudes was there, but multitudes of lambs,

Thousands of little boys and girls raising their innocent hands.

Now like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song,

Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of Heaven among.

Beneath them sit the aged men, wise guardians of the poor;

Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.