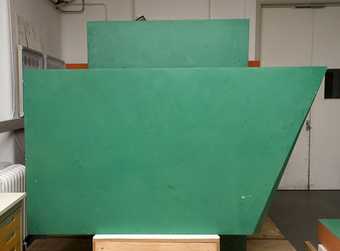

The condition of Call before treatment

Archive photograph of Call (1968) by Phillip King, late 1960s/early 1970s.

Call 1968, a major work by British sculptor Phillip King, was conserved prior to its display at Tate Britain in 2008.

The work comprises four large welded steel units painted in vibrant shades of green and orange. When installed following the precise layout determined by King, the colours and forms play off and enhance one another, creating a crisp and vibrant viewing experience.

Before it could be displayed, the sculpture required treatment because it had accumulated paint losses, scuffs, and a layer of dirt, which obscured the bright colours and subtle relationships of the painted surfaces. In addition, a coating layer on one of the four components had degraded and appeared whitish, very matte, and patchy.

Dirt and grime accumulation on the surface of one of the columns.

Patchy, whitish degraded coating and paint losses on the green box element of the sculpture.

Discussions with the artist

Phillip King had been interviewed by Tate sculpture conservators about Call 1968 on several occasions. When he looked at the work in 2007 with Laura Davies, sculpture conservator, and Clarrie Wallis, curator, he was dissatisfied with the appearance of the sculpture and advised that the only way to restore it might be to repaint.

At the time it was thought that the sculpture had in fact been extensively repainted already and that some of the colours had altered dramatically.

Analysing the paint used on the sculpture

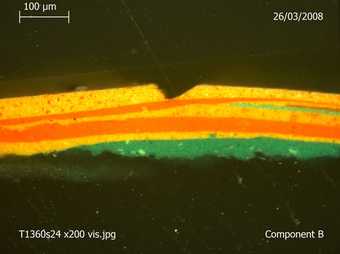

Magnified view of cross-section of paint layers taken from one of the columns, showing King's technique of painting the sculpture in layers.

A research project began at the end of 2007 to investigate more closely King’s 1968 technique and the true condition of the sculpture. Minute samples of paint were taken and analysed. This identified the type of paint used as a polyurethane-modified alkyd, a durable and stable medium.

Examination of cross-sections of the paint and coating layers by visual and ultraviolet microscopy demonstrated the way King had achieved the final colours of the sculpture by building up layers of different shades and using specialised pigments and paint mixtures. The cross-sections also indicated that much if not all of the paint was original. Further examination and cleaning tests showed that the paint was in good condition with still vibrant colours underneath layers of dirt and degraded coatings.

Conserving the sculpture

With this new information, it was decided that it would be possible to carry out a less invasive treatment to conserve the painted surfaces. Instead of sanding down the original paint and repainting the sculpture, cleaning tests fortunately revealed that a more conventional conservation treatment would be successful and the original paint could be cleaned to remove the dirt layer and reduce the degraded coating. Through this treatment the subtle character of the painted surfaces as achieved by King in 1968 would be preserved, while still recapturing the bold colours, clean lines, and unified surfaces essential to the work’s impact.

First, cleaning of all the surfaces was carried out. Following cleaning, areas that remained patchy with the residue of the degraded coating were lightly varnished to saturate the colour and unify the surface.

Green box element during cleaning. The very front surface of the green box has been cleaned. The rectangular surface in the background and the sides of the sculpture still exhibit the degraded surface coating and dirt accumulation.

One surface of the red box element during cleaning. The area in the foreground has been cleaned. The area in the background still exhibits accumulated dirt and grime.

Paint losses were filled flush with acrylic putty and retouched with conservation-grade acrylic dispersion paints, mixed to match the colours of the surrounding paint precisely. The varnish and retouching paints used are fully reversible, meaning that they can be easily and safely removed in the future should the need arise.

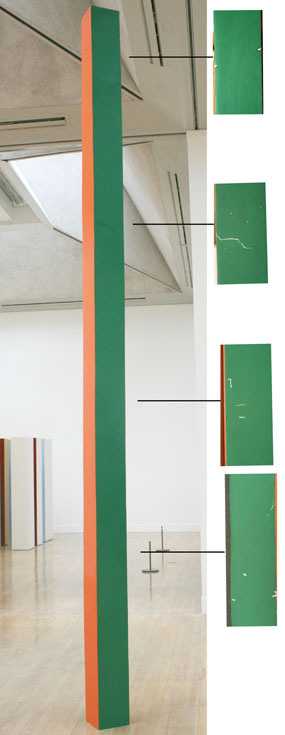

The overall view on the left shows one of the columns after cleaning and retouching of paint losses. The detail views on the right show the paint losses before treatment. The black lines indicate the general location of the details on the overall view.

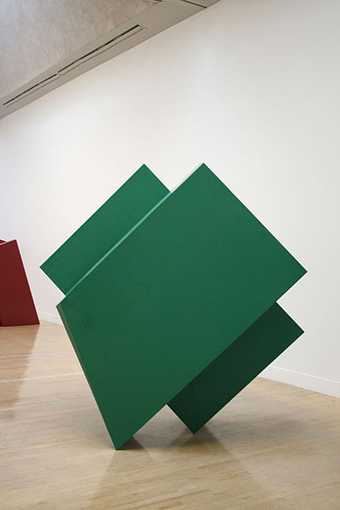

Green box element after cleaning, selective varnishing to reduce patchiness of the surface, and retouching of paint losses

Overall view of Call by Philip King installed in Tate Britain galleries after treatment

Installing the sculpture at Tate Britain

Once the restoration had been completed, the sculpture was then installed at Tate Britain in June 2008. Throughout the installation Tate art handling technicians worked closely with King, following his precise layout, so he had the opportunity to view the newly treated work and was very pleased to see it returned to good condition, as he expresses below.

While the careful preservation and conservation of the original painted surfaces of large-scale sculpture is sometimes seen as impossible, the treatment of Call 1968 demonstrates that such an approach can be effective.

The artist’s reaction to the conservation

After viewing Call 1968 and another of his sculptures, Nile 1967, during installation at Tate Britain, King wrote to Tate Conservation:

I was quite astounded and pleasurably so when having seen both of my sculptures at the Tate recently, I discovered that they had been restored and not repainted. I must say that this painstaking approach pays off and I am most grateful that such effort was put into the restoration. It’s magic; I don’t know how they do it! The work looks exactly as I remember it, and because the space allocated is so generous, I can’t remember an occasion when these works looked remotely as good. Please convey my deep thanks to the restoration team and the curators.