Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Installation View, Photo ©Tate (Joe Humphrys)

Introduction

Each material has its properties, physical and even spiritual.

El Anatsui

Staged as an artwork in three acts, El Anatsui’s cascading metal hangings transform the Turbine Hall. Thousands of repurposed liquor bottle tops and metal fragments were crumpled, crushed, and connected by hand with copper wire into unique compositions. Later, large sheets were pieced together to form massive abstract fields of colour, shape, and line. Despite being monumental in scale, the works are flexible and adaptable to change. Descending from the Turbine Hall’s ceiling, Anatsui’s symphonic sculptures hang in the air and seem to float across the space.

You are invited to embark on a journey of movement and interaction through the hangings, a dance between bodies and sculptures. Anatsui’s free-flowing forms challenge the building’s industrial scale and open up different ways of looking. Viewing the hangings from afar reveals a landscape of symbols: the moon, the sail, the earth, and the wall. Up close, the logos on the bottle tops speak to their social and material life as commodities. As products of a global industry built on colonial trade routes, they connect the overlapping histories of Africa, Europe and the Americas. Revealing the poetic possibilities of his materials, Anatsui explores the entangled relationships and geographies that bind us together.

ACT I: THE RED MOON

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act I The Red Moon, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act I The Red Moon, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

The Turbine Hall reminds me of a ship. I was thinking about motion and the idea of the red sail. This work addresses a history of encounter and the movement of ideas and people.

El Anatsui

The first hanging on the ramp resembles a majestic sail billowing out in the wind. Ships have transported people and goods around the world since ancient times. During the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved African peoples were sold and exchanged for gold, sugar, spirits and other commodities. They were then taken across the ocean towards the Americas, with many labouring on sugar plantations that fuelled the alcohol industry. Later, spirits produced in the Caribbean would be shipped to Europe, and from there to Western Africa. The bottle tops used in this commission derive from a trade network of present-day commodities rooted in colonial histories.

This red and yellow sail might announce the beginning of one such journey across the unforgiving waters of the Atlantic Ocean. At the height of the transatlantic trade in the 18th century, sailors would sometimes use the moon to guide their journeys. Its gravitational tug as Earth’s natural satellite also sets the rhythm of the ocean’s tides. Here, red bottle tops form the outline of a red ‘blood’ moon, seen during a lunar eclipse. Elemental forces interweave with human histories of power, oppression, dispersion and survival.

ACT II: THE WORLD

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act II The World, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Joe Humphrys)

I use multiple elements to talk about the world: not a world made up of just one culture, but a world shaped by all of us coming together.

El Anatsui

The sculpture in front of the Turbine Hall bridge is composed of multiple layers. They suggest a loose grouping of human figures, suspended in the air in a state of movement. When viewed from a particular position on the bridge, the fragmented shapes converge into the single circular form of the Earth. The circle echoes the red moon of the sail as a fellow celestial body. Anatsui has a longstanding interest in the fragment as a symbol of renewal and restoration. He has said that ‘breaking is not destruction but a necessity for reforming.’

As separate elements, the group of restless human forms might imply dispersion through the migration and movement of people across the globe, both forced and voluntary. When viewed together, the fragmentary circle gestures towards new formations of collective identities and experiences. Anatsui also plays with the tension between transparency and opacity. The ethereal appearance of the figures is achieved using thin bottle top seals wired together to create a semi-transparent, net-like material.

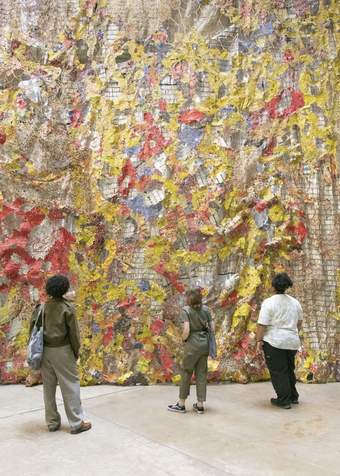

ACT III: THE WALL

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act III The Wall, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Act III The Wall, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

Tate & Lyle sugar was the only brand we used during my childhood in the Gold Coast. I came to understand that the sugar industry grew from the transatlantic trade and the movement of goods and people. My idea is to play with all these elements.

El Anatsui

In this final act, a monumental black wall stretches from floor to ceiling. Anatsui’s interest in walls is rooted in the ancient story of the earthen wall of Notsie (present-day Togo). Built by King Agokoli to confine and oppress his subjects, a revolutionary uprising by the Ewe people led to the wall’s destruction and the Ewe’s escape. As well as structures that constrain and encircle, Anatsui also speaks of the productive quality of walls as ‘... an attempt to hide things. They provoke curiosity and curiosity might get imagination out to the other side.’

Facing the yellow back of the sail, the wall might suggest an arrival at shore. Metal pools rise from the ground at the base of the wall, resembling crashing waves and rocky peaks. For Anatsui, the use of black refers to the continent of Africa and its global diaspora, charged with the potential of homecoming and return. Moving behind the wall reveals an edifice of shimmering silver, covered in a multi-coloured mosaic. As lines and waves of blackness and technicolour meet, they echo the collision of global cultures and hybrid identities that Anatsui invites us to consider throughout the commission.

ABOUT EL ANATSUI

Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Installation View, Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

At the centre of Anatsui’s artistic practice is a longstanding interest in humanity’s disruption of the Earth’s natural order. His artworks engage with histories of connection and displacement, transforming commonplace materials into vast sculptural compositions. When working with bottle tops, sourced in Nigeria, the artist reckons with ‘the material which was there at the beginning of the contact between two continents.’

Anatsui is aided in his studio work by dozens of assistants. They work together to stitch and assemble his sculptures by hand. Connections are made organically between materials, shapes and colours as compositions are pieced together. The flexible hangings which emerge embody Anatsui’s idea of the ‘non-fixed form’ - they can appear in different arrangements at each separate installation. Anatsui’s work also engages with global histories of abstraction. ‘When I started working with abstraction, I saw the freedom and the challenge that comes with it,’ the artist has said. ‘You are not contributing to the world by replicating what is there already.’

El Anatsui was born in Anyako, Ghana in 1944. He currently lives and works from Tema, Ghana and Nsukka, Nigeria.

Audio description tour

This in-depth tour has been created with visually impaired visitors in mind, but can be enjoyed by anyone.