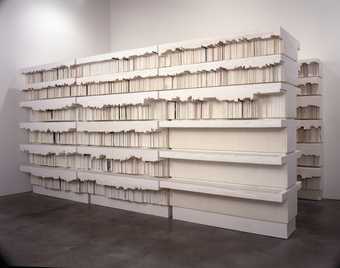

Rachel Whiteread Untitled (Book Corridors) 1998 © Rachel Whiteread

1. Her work makes the invisible visible

Whiteread’s work typically takes the form of casts, which are formed when a liquid material is poured into a mold and allowed to solidify. Using materials like concrete, resin, and even snow, her sculptures take the shape of everyday objects: mattresses, hot water bottles, stairwells, and the like.

But more often than not, Whiteread’s casts are of negative space, or the space between, under, or otherwise around things. The space that surrounds and defines an object is what we see in her sculptures. Look closely at Untitled (Book Corridors), and you’ll see that what initially registers in your mind as books on shelves is actually a cast of the spaces between shelves. There are no books or shelves left in the work, only the ruffled edges of pages torn out. It’s the invisible spaces around us that Whiteread has turned our focus to.

2. She was the first woman to win the Turner Prize

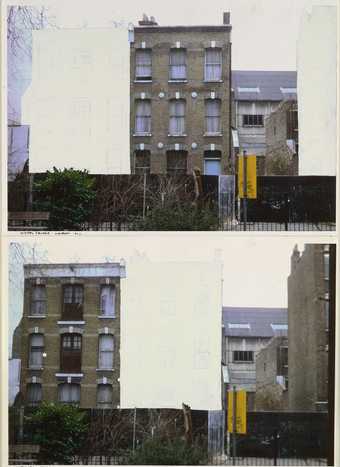

Rachel Whiteread Study for House 1992 © Rachel Whiteread

Whiteread was awarded the Turner Prize in 1993 following her project Untitled (House), a life-sized cast of a condemned terraced house in London's East End. The work was a concrete cast of the inside of the entire three-story house, from basement to top floor. The casting took three months to complete, and because the final work was so heavy, it was exhibited at the location of the original house. Meanwhile the terraced houses that once surrounded it were demolished to make way for new developments. Set next to an old Roman road, with a view to the rising skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, House told the story of redevelopment in London’s East End.

In November 1993, Whiteread became the first woman to win the Turner Prize. On the very same day, the local council agreed to demolish the work following a heated public debate over letting the work remain. Two months later, in January 1994, House was destroyed by an earthmover over the course of two hours. Nothing remains of it to this day, but it had an indelible impact on British art and sculpture going forward.

3. While they appear minimal, her sculptures are full of emotion, memory, and the macabre

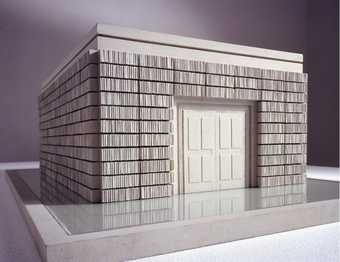

Rachel Whiteread Maquette for Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial 1995 © Rachel Whiteread

Whiteread’s work has been described as 'minimalism with a heart.' This is because the objects she casts – mattresses, beds, sinks, chairs – all have an intimate, physical relationship to the body despite their stark appearance. As objects that are meant to be held, used, and inhabited, their reference point is always human. And because they are always second-hand, they have had a life prior to the artist's treatment of them, and bring their own histories to her work.

Some of her work addresses particular human stories, like the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial, or Nameless Library in Vienna. Endless copies of unreadable books, their spines turned inwards, convey feelings of multitude and loss. Other objects, like mattresses and hospital beds, create casts that memorialise everyday moments of life and death.

4. Born and raised in London, the city is at the heart of her practice

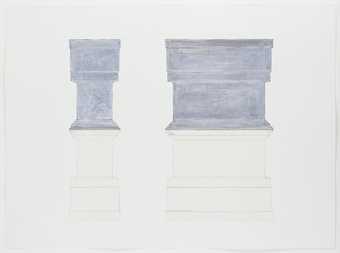

Rachel Whiteread Trafalgar Square Project 1998 Gagosian Gallery © Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread was born in Ilford, East London, in 1963. She studied painting in Brighton from 1982 to 1985 and sculpture at the Slade School of Art in London from 1985 to 1987. Along with her focus on everyday objects, Whiteread’s work has taken a particular look at London and the politics of urbanisation, development, and life in the city.

Whiteread’s Room 101, for example, is the cast of a room at the BBC’s Broadcasting House in London, a room said to have inspired the torture chamber in George Orwell’s 1984. And House, for example, was a way of responding to the threat posed to older London houses by ongoing campaigns of development and modernisation. Speaking about the project, the artist has acknowledged that it had a socio-political dimension and talked about the 'ludicrous policy of knocking down homes like this and building badly designed tower blocks which themselves have to be knocked down after 20 years’.

5. Whiteread’s sculptures have to be seen to be appreciated

Rachel Whiteread Line Up 2007-2008 Gagosian Gallery © Rachel Whiteread

While they might appear straightforward at first glance, Whitread's sculptures always have deeper stories to tell. They capture the negative spaces around us, or use familiar materials in unexpected ways. Or they might trick us into thinking they're something they're not. Like Line Up, which looks like nothing but toilet paper rolls, but is really made of plaster, pigment, resin, wood and metal.

Look closer at a Whiteread sculpture and you'll find things you didn't think were there: surprising materials, unseen spaces, and the human stories hidden within them.

Rachel Whiteread is on at Tate Britain 12 September – 21 January 2018