The great twentieth-century cartoonist David Low described William Hogarth as the grandfather of the political cartoon. What he meant was that while Hogarth didn’t quite set the template for political cartoons as we now recognise them (Gillray did that a generation later), the medium wouldn’t be the same without him. There’s a great deal of truth in this, but not necessarily for the obvious reasons. Hogarth refined a pre-existing tradition of visual satire, taking it to previously unscaled heights of sophistication and skill. And, through the popularity of his output, he placed visual satire shoulder to shoulder with the textual satire of the times (the elderly Swift wrote a poem to the young Hogarth, praising him and proposing that they collaborate). But he also established a journalistic tradition that’s still flourishing today.

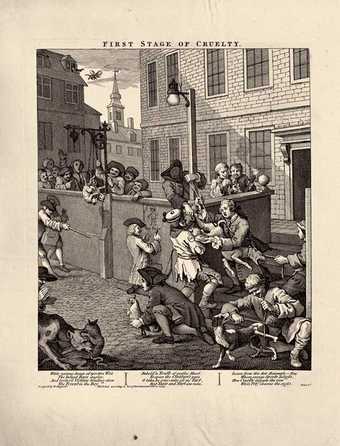

Hogarth was in many ways a contradictory figure: a satirist who wanted to be part of the Establishment; a popular engraver who wished to be recognised as a serious artist. He succeeded in being all these things (although, in the first instance, at great personal cost). But first and foremost he was a polemicist. That may seem to be a pretty obvious thing to say when you look at A Rake’s Progress 1735, or A Harlot’s Progress 1732, or The Idle and Industrious Apprentice 1747, or Stages of Cruelty 1751. But what’s truly interesting is the way he did it, because it was essentially contradictory. Take his most famous print, Gin Lane 1751. At face value it is identical, in intention and effect, to a modern tabloid headline. It was inspired by a news story Hogarth heard about a woman who murdered her infant daughter so she could sell her clothes to buy gin – the equivalent of a banner headline today about teenagers killing an OAP to steal a fiver to buy crack. It’s meant to shock; moreover, it’s meant to shock its reader (viewer?) into better behaviour. Thus its companion piece, Beer Street (also 1751), showing the advantages of honest English ale over evil foreign gin. To this end it was sold cheaply in order to reach as wide an audience as possible. In other words, it was a kind of proto-popular journalism, the first glimmer of the developing mass media.

And yet Gin Lane works on far more levels than that, quite apart from being a much better and more powerful image than Beer Street. For a start, it’s an image of eighteenth-century London that many people probably now take at face value, almost as if it were a photograph. But despite the horror portrayed – infanticide, drunken oblivion, disinterment of corpses, starvation, beggary, poverty, impalement, suicide, debt, debauchery and the collapsing buildings standing as metaphor for the collapse of society in general – it’s also intrinsically funny. True, it’s a very, very dark kind of humour, but there’s a morbid vivacity to it which is entirely absent from the prosperous contentment of Beer Street.

That’s how satire works. You laugh almost despite yourself. The exaggeration is one of the triggers to make you laugh. Although we can pinpoint where Gin Lane probably was, it’s doubtful that such scenes all happened together at the same time – hammering home the horror ad absurdum. And then that contradiction, the disjunction between horror and laughter, makes you laugh again. And then, with luck, you start thinking. That’s exactly how today’s political cartoons operate.

There’s still more to it, and probably more than Hogarth ever intended. Because of its enduring power, Gin Lane has come almost to define what we think we know of the eighteenth century. If a twenty-first-century time traveller went back to Hogarth’s London, he or she would probably be horrified by the stench and the poverty and the crime and the filth, far worse than anything we’d find in our own developing countries. Yet we look at Gin Lane with a kind of amused affection. It’s earthy rather than just shitty; rumbustious and not just repulsive; endearing rather than evil. You can put that down to the redemptive power of passing time, or you could say it was another of Hogarth’s instigating influences: of taking the unspeakable, depicting it visually, leavening it with humour to make it digestible and, moreover, bearable. Modern cartoons do that too.

And remember, whether he intended it or not, there’s a world of difference in our perception between what we understand by a “Hogarthian” and a “Dickensian” slum.