Press cutting from the Manchester Evening News, 31 January 1939

Photo: © James McPhail

© The Manchester Evening News, courtesy The British Library

On 2 February 1939, the Manchester Guardian reported on the progress of a group of Mancunian artists and activists preparing the last ever exhibition of Picasso’s Guernica in Britain. ‘It is a picture that should be seen and judged for oneself,’ the newspaper announced, ‘and those people who do not react readily to the principle picture cannot fail to find a magnificent concentrated energy and fine craftsmanship in some of the preparatory drawings.’ Provoking wide debate about the style and political nature of Picasso’s art, the British exhibitions of Guernica in 1938–9 proved to be a turning point for his reputation in this country – and for a generation of modern artists, including Henry Moore, Francis Bacon and Graham Sutherland, for whom exposure to the painting and its preparatory studies had a decisive effect. Yet unlike Guernica’s outings in London’s New Burlington and Whitechapel galleries towards the end of 1938, the circumstances surrounding its brief appearance in a Manchester car showroom have puzzled historians, so much so that aside from one or two pieces of evidence, the story has remained shrouded in rumour and mystery. As well as thinking more broadly about the significance of Guernica from a British perspective, one of the objectives of Picasso and Modern British Art has been to draw attention to Manchester’s radical anti-war movement, from which a more cohesive picture of the work’s role emerges.

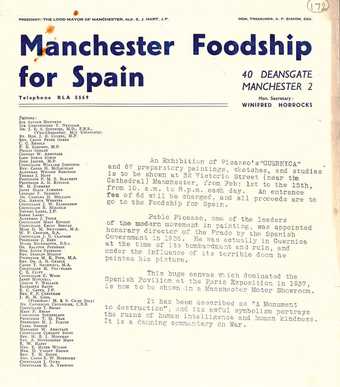

Leaflet announcing the Guernica exhibition, distributed by Manchester Foodship for Spain campaign, 1939

Courtesy The Working Class Movement Library

Masterminded by Roland Penrose, the British exhibitions of Guernica were designed almost exclusively as an exercise in propaganda to highlight the horrors of war. British support for the Spanish Republican cause – political and artistic – had gained considerable momentum by the time Guernica landed on British soil on 30 September 1938, the day Prime Minister Chamberlain signed the Munich Pact. Manchester’s engagement with Spain can be traced from 1933, when the Manchester & District Anti-War Council was formed by a coalition of working-class and left-wing organisations and trade unions. Its propaganda work included a series of shows such as the Anti-War Exhibition at the Friends Meeting House in January 1935 and The Cambridge Anti- War Exhibition near the university in 1938, organised by the prominent Artist International Association founder members Cliff Rowe and Misha Black. The activity of this body was enhanced by a string of subsidiary committees and organisations across the city, including the university’s Anti-War Group, the Manchester Peace Players and, most closely linked to Guernica, the Manchester Foodship for Spain, from whose office at 40 Deansgate 150,000 appeal leaflets were distributed and a mass public rally orchestrated at the Free Trade Hall in January 1939 to mark Manchester & Salford Peace Week.

Manchester Foodship’s role in bringing Picasso’s painting to the city is evident from an official announcement in the collection of the Working Class Movement Library in Salford. Championing Picasso as a leader of the modern movement, it maintains the artist was in Guernica at the time of its bombardment (a grave error, given that we know he began painting Guernica in his Paris studio on 9 May 1937 and, according to his biographer John Richardson, hadn’t been to Spain since August 1934), before describing the work as a ‘damning commentary on War’.

The lack of evidence that the Manchester exhibition took place stems from its unusual location. We know from Penrose’s biography of Picasso (which fails entirely to mention Manchester in its account of the British tour) that it would not have been possible for Guernica to travel so extensively without it being removed from its stretcher and rolled. As the Guardian and Manchester Foodship announcements tell us, those eager to see Guernica did not have to travel to one of the city’s art galleries to encounter it. Instead, the painting and 67 preparatory sketches had been squeezed with inches to spare into a car showroom in the city centre.

How the Manchester Foodship secured this mercantile space at the corner of Victoria Street and Cateaton Street, and then transformed it into a temporary gallery to house the most celebrated painting of the twentieth century, has remained a mystery. But what has emerged more recently is that the work was likely to have been entrusted to a group of local art students. Many graduates of Manchester Art School during the 1930s were heavily involved in the city’s working-class movement and in confronting Oswald Mosley’s mob on its streets. One of these was the Manchester-born artist Harry Baines, a member of the Communist Party celebrated for his public murals in the area. A fitting character to take on the challenge of installing a world-famous work, Baines described shortly before his death his somewhat ham-fisted method of unrolling the large heavy canvas, banging some nails in it and attaching it to the wall.*

For Bernard Barry, a local machinist who joined the Youth Communist League (the largest branch in Britain, also known as the Challenge Club) at the age of sixteen in 1936, it was common knowledge among his peers that Guernica was a ‘must see’. He knew little of Picasso’s work, but recalled when I interviewed him that it was hard to be anything but impressed by the image’s arresting iconography of the horrors of war. On returning after the Second World War, Barry was active in the Manchester peace movement, later documenting the efforts of his comrades, including Sam Wilde, who, inspired by the city’s appeals, joined the International Brigade, becoming its national president in 1939. Another of those involved, Jud Coleman, wrote in October 1937: ‘As anti-Fascist and class-conscious workers we realise that only by victory and the defeat of Fascism can there be any real future for human society.’

It is unsurprising that accounts of Guernica’s reception in Manchester are heavily entrenched in the response to the Foodship appeals, as shortly after the exhibition’s opening, £3,000 was cabled from Manchester to Europe to buy milk and food for civilian refugees and children. ‘Not only is food needed,’ exclaimed the Foodship’s treasurer A.P. Simon at the opening of the show, ‘but it can get through. The Picasso exhibition is one of the Foodship Committee’s efforts to raise funds.’