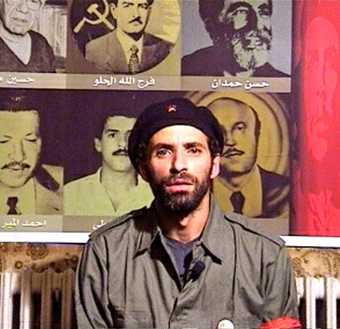

Video still of Rabih Mroué's On Three Posters 2004

Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut

Why did you select this video work by Rabih Mroué for the In Focus project?

On Three Posters is one of the most conceptually rich and multi-layered works of recent times to question the use of images as an ideological weapon in wars. Re-staging a videotaped martyr testimony made in 1982 by Jamal al-Sati, a fighter for Lebanon’s National Resistance Front, Mroué examines the correlation between electronic media (specifically video and television) and death in Lebanese territorial conflicts of the ‘civil war’ period 1975–1990. In contrast to the definitive version of al-Sati’s testimony broadcast on Lebanese television, the original videotape shows three takes of his martyr testimony. The three versions, each minutely different from each other, prompted Mroué to question the truth-status of suicide videos and martyr posters, and to examine the ideological circumstances surrounding their production and place within the visual culture and political history of Lebanon.

On Three Posters has received some critical attention but most of the writing has tended to focus on the philosophical issues posed by the work and does not consider what the video might have to tell us about the violent elimination of the Lebanese leftist militias in the 1980s. The In Focus casts much-needed light on the intersection of biography and political histories in this work.

Can you explain why it is called On Three Posters?

The title refers to three different protagonists that are taken up in each section of the video: an actor, a resistance fighter, and a politician. More literally, the reference to posters refers to the images of martyred men and women that populate the walls of Lebanese cities and towns. Recalling his experience of living through the long period of ‘civil war’ in Lebanon, Mroué commented: ‘one day, suddenly, we would see the poster of a friend hung on the walls of Beirut, or a photograph or video on the TV announcing his or her death’. I suggest that On Three Posters is also an attempt to bring these seemingly static images of death into dialogue with electronic images that serve to re-animate the deceased, creating what I call ‘posthumous images’.

Truth and fabrication are called into question in this piece in ways that can be seen as both purely philosophical but also political. How would you account for these seemingly contradictory interpretations?

Although On Three Posters deals with very real histories, its re-staging of those histories serves to cast doubt on the notion that a video or any other historical artefact might serve as irrefutable evidence of the past. I think it is true to say this blurring of the lines between fact and fiction (which is a much-noted feature of contemporary art from Lebanon) has sometimes been miscast as a form of post-modern relativism characterised by media scepticism and a broader suspicion of historical truth. By manipulating his sources, Mroué reminds us that the interpretation of history is never neutral or disinterested: it is often the result of particular ideological visions. This is especially true in Lebanon where the question of how to write and, indeed, teach, histories dealing with the violence of the recent past remains a source of deep political conflict. Although these histories are deeply contested and resist any search for conclusive truths, I do not think that the entanglement of this art with the mythologies and traumas of the ‘civil war’ absolve us of the ethical task of asking what kind of documentary practice might serve as a basis for a politics of truth.

How important do you feel it is to understand the Lebanese political context of this piece?

Extremely important. It is crucial to remember that the original performance Three Posters was a context-specific work, written and staged with a Beirut audience in mind. On Three Posters examines Jamal al-Sati’s actions as part of wider practice of secular martyrdom linked to left-wing political struggles in Lebanon. Unfortunately, this subtext was largely lost on foreign audiences and critics who insisted on linking the work to contemporary debates surrounding Islamic terrorism in the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks. This fixation on more recent suicide attacks often avoided any discussion or analysis of the longer history of martyrdom within Islam. For Mroué, it was a challenge to keep Three Posters free from ‘current events’ and to insist instead on its Lebanese context. In Beirut Three Posters was intended to function as an ‘auto-critical assessment of the Left’s absence today in the Lebanese political arena.’

In your project you discuss this work in relation to the work of other contemporary Lebanese artists. Are there parallels to be drawn with the work of artists outside of the Middle East?

Absolutely. On Three Posters raises questions about documentary evidence, collective memory and state-sanctioned amnesia that powerfully resonate with the work of other artists working through histories of unspoken violence. I am thinking here of works like Willie Doherty’s Re-run 2002, a video that deals similarly with questions of trauma and historical repetition in relation to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. I also see parallels with Omer Fast’s video The Casting 2007, a seemingly improvised though likely scripted interview/screen-test with a US army sergeant. Like Mroué, Fast uses strategies of re-enactment and image manipulation to foreground the way that memories become stories and the way that those memories become mediated in times of war. As the soldier/actor narrates two disturbing experiences while stationed in Europe and then in Iraq, we are led to doubt whether this is a real soldier or in fact an actor auditioning for the part.