As part of the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum (2018–22), Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972 was chosen as the focus of intensive research that considered what it meant for this complex experimental performance of music and film to enter the museum.1 Specifically, the research team and staff involved across Tate sought to investigate how the work could be acquired, documented, conserved, and performed and transmitted in future, given that the work has no formal score and that Conrad had died in April 2016, not long before the formal acquisition process began.

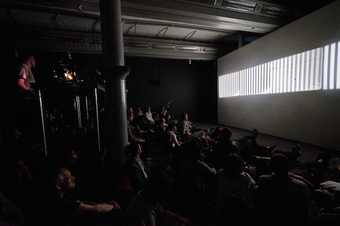

Fig.1

View of the performance of Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972 at LightNight, Tate Liverpool, 17 May 2019, showing the start of the performance, with the audience sitting on the floor in the darkened gallery space and projectionist Rob Kennedy behind them, manipulating the 16 mm projectors

Performance, musical instruments and film, 16mm, 4 projections, black and white, and sound (stereo)

Duration: 90 min

Photo: Mark McNulty

Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (hereafter Ten Years Alive) is a live work that was first performed at the experimental arts venue The Kitchen in New York in 1972. Lasting ninety minutes, this mesmerising minimalist work for amplified strings has been performed in different configurations during its lifetime. The most recent instance was at Tate Liverpool in 2019, where it was performed with the following instruments: two violins (one played live and one played by Conrad on a recording), a bass guitar and a ‘long string drone’, which is an instrument invented by Conrad. The sound element was accompanied by four 16 mm film projections. Throughout the performance, the bass guitar plays a single pulse on a single note: C#. The long string drone has three strings and the sound is created by hitting these with an object such as a solid steel guitar slide and creating a glissando as the slide is drawn along the strings towards the centre of the instrument.2 The drone sound is created by the violins slowly drawing the bow over two strings. During the course of the performance, the film projectors show film reels featuring black and white vertical stripes (fig.1). By physically moving the projectors little by little during the performance, these projections come together as one pulsating square.

Fig.2

The new generation of performers rehearsing Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain for the LightNight performance at Tate Liverpool, 2019, with documentary filming being carried out by Will Wilkinson. Performers from left to right: violinist Catherine Landen, long string drone player George Maund and bass guitar player Emily Lansley

Photo: Roger Sinek

From our first encounter with this experimental music and film work a year after Conrad’s death, it was clear that in order to think about how this work might enter Tate’s collection, the museum needed to develop an understanding of the social networks that surrounded Ten Years Alive and their evolving role in sustaining the work. We also needed to develop new ways of thinking about distributed knowledge and authority around a work of art held within a museum collection. The occasion that brought this thinking and this network together for the first time at Tate was the performance of the work in The Tanks, Tate Modern on 18 January 2017. Thanks to the foresight of Tate curators Andrea Lissoni and Carly Whitefield, this performance provided a moment to bring together those who had supported this work, and Conrad’s work more generally, in order to co-create the way in which the work might continue without Conrad’s presence as its primary instigator, transmitter, teacher and ‘first’ violinist. Building on the questions and ideas raised by this 2017 performance, the Reshaping the Collectible project was to carry out an experiment at Tate Liverpool in 2019 to test the efficacy of transmitting Ten Years Alive to new performers through a dossier of information consisting of text, images and video (fig.2).

Reshaping the Collectible: Tony Conrad, Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain presents the processes, experiences, methodologies and outcomes of this research. This introduction outlines the six different written contributions that make up the publication: ‘“Yes, But How Can It Be Live and Collectable?”: Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972’ by Lucy Bayley; ‘Ecologies of Memory in the Conservation of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain’ by Hélia Marçal; ‘Experimenting with Transmission’ by Hélia Marçal, Louise Lawson and Ana Ribeiro; ‘Method for Assessing Conservation Documentation for Complex Performance Artworks’ by Louise Lawson and Hélia Marçal; ‘Institutional Practices: Collecting Performance Art at Tate’ by Louise Lawson, Stephen Huyton, Hélia Marçal and Ana Ribeiro; and ‘Assessing the Status of the Long String Drone’ by Stephen Huyton.3 Together, these texts describe the research findings from this case study and the 2019 Tate Liverpool experiment. As I will outline later in this introduction, they provide a mix of art historical analysis, practical tools related to collecting and transmitting live performance works, methodologies for creating such tools, and more theoretical pieces of writing that offer a framework through which the life of performance works in a museum collection can be understood.

The research addressed a number of key questions in response to this artwork as it became part of Tate’s collection. Does a performance artwork without a score have to be ‘fixed’ in some way by the museum in order for the work to live within it? What does it mean for the museum to become part of an existing network that has cared for and sustained a work for more than fifty years? What have we learned from Ten Years Alive to advance practice in the documentation and transmission of performance art more generally? In addressing these questions, this study of Conrad’s Ten Years Alive represents a development in the way in which the conservation and the stewardship of performance is approached within the contemporary art museum.

Tate Liverpool experiment, May 2019

Fig.3

Participants discussing the closed performance of Ten Years Alive during the feedback session, Tate Liverpool, 16 May 2019

Image: Roger Sinek

Fig.4

New performers Emily Lansley (centre) and Catherine Landen (right) discussing the ‘dossier for transmission’ during rehearsals for the LightNight performance at Tate Liverpool, 2019

Photo: Roger Sinek

In a room at Tate Liverpool sat a circle of people with one thing in common (fig.3). Through their different forms of practice, they had all been engaged in the care of an artwork: Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain. In the innermost part of the circle were those who had performed the work before with Conrad, some more than once. These were the ‘transmitters’ – as we came to call them – of a work that was first performed in 1972, and alongside them were a group of musicians who had just played the work live for the first time. Gathered around these performers were conservators, curators, registrars, technicians and academics. For the ‘closed’ performance of Ten Years Alive that had just taken place, the performers had worked from a dossier of information that drew on the knowledge of the work’s transmitters that, in their different ways, continue to support Ten Years Alive and the artist’s legacy (fig.4).4

The conversation in which this varied group of people were engaged examined what had been conveyed and what had been lost in the transmission of this work, with the exchange focusing on the ‘embedded know-how’ of those assembled.5 One of the transmitters read from notes she had written during an earlier experience of playing the piece: ‘I’m worried about putting the violin down, because my left hand is hurting and if I put it down I may never be able to pick the violin back up again. So, this piece for me is a real physical piece. It’s physically demanding.’6

This gathering in Liverpool was part of the process of bringing Ten Years Alive into Tate’s collection, one that had started with the discussions between the curator Andrea Lissoni and Tony Conrad shortly before the artist’s death. This process, which was completed in spring 2020, presented a number of challenges to Tate’s conservation practices, as documented in ‘Institutional Practices: Collecting Performance Art at Tate’ by Lawson, Huyton, Marçal and Ribeiro. Although the institution had fifteen years of experience collecting live performance-based art, this particular acquisition raised questions such as: what does this work teach us about how to understand conservation practice? What is the significance of understanding this work as situated and stewarded within a network of ‘transmitters’?

A key challenge that we faced related to the absence of the artist. Within the contemporary art museum, in the normal course of things, artists work closely with museum staff to pass on knowledge about their work and are interviewed when a work is acquired to help consolidate its identity. This process often serves as one of the technologies of the museum that detach the work from the artist, transferring knowledge and authority to the museum.7 Ten Years Alive was the first live work to be acquired by Tate that was not designed to be performed independently of the artist; instructions were not passed to the museum in the usual way through the standard tools described above. The work had no score – Conrad was vocally against scores – and instead was taught in person, often by Conrad, to new performers in the days and hours leading up to a performance of the work.8

Furthermore, it was difficult to gauge the degree to which the piece allowed for variability and interpretation by the individual performers. As documented in Bayley’s ‘“Yes, But How Can It Be Live and Collectable?”: Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972’, across the fourteen performances that have taken place during its lifetime, Ten Years Alive has assumed several forms: there have been different numbers of performers and variations in the configurations of the instruments and the film projections.9 Despite this variability the work also has a strong underlying structure and, as observed by Marçal, Lawson and Ribeiro in ‘Experimenting with Transmission’, the tension between allowing for variation and respecting this structure was keenly felt by all those concerned with the transmission of the work. The challenge of allowing a degree of openness and maintaining that openness is significant without the presence of the artist. Artists commonly revisit their work and engage with it as the product of their ongoing emergent practice, allowing the work to unfold. However, the conservator and the curator will approach a work from the point of view of their own practice, which is more inclined to fix the work.10 This is because, as the sociologist Fernando Domínguez Rubio has observed, conservation is a form of mimeographic labour enacted within the museum, where the museum is seen as a machine designed to keep things the same.11 With a performance work, performers take on the delicate balancing act of judging how much interpretation is appropriate.12 When the artist is no longer present, the act of performing therefore maintains a tension between the work’s potential to continue to develop and unfold, and the museum’s tendency to fix it.

Fig.5

Restringing the long string drone in preparation for the LightNight performance at Tate Liverpool, 15 May 2019

Photo: Roger Sinek

The preparation for the performance at Tate Liverpool – including the readying of equipment and film prints; the assembling of spaces and people; the testing; the shipping; the building; the unpacking; the restringing and tuning of instruments; the checking; the documenting – revealed the close attention to the specificity of the human and non-human material that makes up Ten Years Alive, especially in the absence of the artist (fig.5). Through his absence Conrad influenced our research, principles and practice, and influenced this resulting publication in three important ways: in our approach to the idea of care; in our understanding of Conrad as teacher and instigator of the work; and in the way that authority is manifested and challenged in Ten Years Alive through the networks that maintain and care for it. I will now explore each of these three ways in which Conrad’s absence impacted our work, before moving on to discuss how these and other ideas play out in the six individual papers that make up this study.

Care and the museum

While the week that we spent at Tate Liverpool in May 2019 culminated in a public performance of the work, what had also been performed was conservation as a social activity that involved people and things which extend beyond the museum. Crucially, we had also demonstrated how conservation and its associated practices are practices of care.

Care emerged as an important concept for our research as a way of connecting the practices of care within the museum to the wider world, highlighting the social and relational nature of our work with Ten Years Alive. The political scientist Joan Tronto and feminist educator Berenice Fisher define care as ‘everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair “our world” so that we can live in it as well as possible’.13 In relation to the care of art, the art historian Alexander Nagel has observed that ‘The protracted performance set in motion by works of art can become the work of whole societies’. In stating this, Nagel suggests that inherent in the logic of care is the ‘return of the performative dimension of art’, the ‘process and investments that go into contending with the life and death of objects’, and that this is work that can become the responsibility and endeavour of entire societies.14

While care became an important framework for our research, we also acknowledge that it is not an untroubled concept: caring builds value, and not caring signals what we consider worthless.15 Care is as much about what we neglect as what we look after. In this time of pandemic, war, great social and racial inequity, and climate crisis, and within a capitalist society, the logic of scarcity dominates discussions of care, which are centred on the controlled distribution of limited resources.16 Within the museum, care has been harnessed as part of the imperialist discourse, rooted in colonial legacies that assert the dominance of one way of caring over any other, and asserting a paternalistic notion of ‘care-as-protection’.17 For example, the suggestion that countries of origin are not able to care for looted objects is still offered as a reason for not carrying out the restitution of these works to museums in their home countries.18 The inability to conform to strict environmental conditions for objects in terms of stable temperature and humidity – conditions that are determined by ‘international standards’ – is a reason that is used by wealthy museums to decline the return or loan of objects to institutions around the world.19

However, the framework of an ethics of care can also encourage us to think about and present the work we do in new ways, challenging the supposedly neutral voice of the museum and foregrounding the social embeddedness of this work. We can do this by making visible the care and caregivers that make up the distributed network surrounding Ten Years Alive, and by asserting and acknowledging the individual contributions to the work’s care. When Ten Years Alive began its journey into Tate’s collection, the museum was granted a license to care, to assume its responsibilities in becoming part of a pre-existing network of care. The museum can also be shaped by the object of its care; for example, our work on Ten Years Alive led to shifts in our wider practice in relation to contributorship, the understanding of institutional memory, and our documentation practices, among others.

What was the focus of the care work for Conrad’s Ten Years Alive as it entered the museum? What is it that we are working to maintain, continue and repair? Prior to its acquisition by Tate, the care work in relation to Ten Years Alive had been undertaken by the network of those who had performed, curated, organised, produced, written and thought about the work since it was first performed in 1972. The maintenance of the knowledge of how to perform Ten Years Alive and its significance was care work performed over a long duration. But this changed in 2016 with the death of Conrad. One element of the work’s performance – Conrad performing one of the two violin parts – was gone. Anthropologist Shannon Mattern has written about care as an act of ‘connecting threads, mending holes’,20 and for Ten Years Alive the first piece of mending required was the use of a recording to replace the live performance of Conrad on violin. In an interview, Conrad’s widow, the artist, activist and scholar Paige Sarlin, outlined how the use of recordings had begun when Conrad was too ill to play live towards the end of his life. The recording thus operated as a darning patch which enabled the work to continue to be performed without him. This way of filling in the holes also allowed the work to carry on being performed after Conrad’s death.21

Many practices of care that take place in the museum are far less visible or celebrated. Conservators, archivists, registrars and art handlers have made a virtue of invisibility in their care work,22 and the labour of conservation might be seen as unproductive – an expensive ‘hidden cost’ as compared to the productive labour involved in work that has visible outputs, such as exhibitions, displays, acquisitions and loans.23 The set of papers that comprise this publication bring much of this hidden care work to light. In the paper ‘Institutional Practices: Collecting Performance Art at Tate’, Lawson, Huyton, Marçal and Ribeiro lay bare the processes involved in bringing a complex artwork into the museum from the perspective of Tate’s time-based media conservation team and collection management department. They make visible the way that artworks become museum objects through the pre-acquisition, acquisition processing and post-accessioning phases at Tate.

At the same time, Lawson, Huyton, Marçal and Ribeiro remain conscious of and troubled by the drive of the museum to fix its objects’ identities through practices of care. This is particularly relevant in the case of Conrad: as Bayley writes, ‘Is there not a risk that without the artist present to author changes and reposition the work in the present it will start to become fixed, with a definitive iteration as the reference point?’. Can Ten Years Alive continue to be shaped by its transmitters? Can it break from ‘a circuit of its own history’?24 Marçal, in her essay ‘Ecologies of Memory in the Conservation of Ten Years Alive On the Infinite Plain’, suggests that Ten Years Alive resists what Domínguez Rubio describes as the museum’s ‘objectification machine’ because ‘the memories that surround the making and activation of the work are essential to its transmission, and yet they do not, and cannot, belong to the museum’.25 This essential knowledge of the work necessarily sits outside the museum, and ‘is distributed by and among the many people and ecologies who hold the memories of how to perform it’. For Marçal, this opens up the idea of ‘the commons’, derived from the work of Felix Stalder. ‘The commons’ is made up of goods that can be used communally and that are administered by the community, and of practices, norms and institutions that are developed by the communities themselves.26 In Marçal’s view, a move towards the commons is achieved through practices of affirmative ethics, a process whereby a negative pattern is identified within a process or institution and a commitment is made to change.27 This provides a powerful glimpse into the potential for museum practice to evolve beyond its foundational colonial logic and towards what has been described as the ‘museum of letting go’:28 a museum that allows for shared participation and, importantly, shared decision making.

Conrad as teacher and instigator of the work

With Conrad’s death, his role as the teacher of Ten Years Alive was also gone. Conrad had taught the piece to new performers prior to each showing of the work, creating a social connection with those involved. Although Conrad questioned and explored his own complex relationship to authority and power throughout his career,29 he was the main authority regarding the piece, travelling to the host venue a few days before each performance to teach the work to a new set of performers, and sometimes taking a trusted performer with him for company. Lectures often accompanied his performances and by all accounts these were very humorous. Reflecting on an introduction that Conrad gave to a performance at Café OTO, London in 2014,30 the curator María Palacios Cruz said: ‘the way he did it … transforms the audience into finding it all very funny, or accepting it or opening it up, or not finding things hermetic or difficult. So that’s the thing … if you see his work without him, his work can be very dry.’31 The significance of intimacy in the transmission of Ten Years Alive is explored by Marçal in her ‘Ecologies of Memory’ paper, in which she shows how bodily knowledge and affect, as well as Conrad’s character and personal relationships, were and are key to performances of the work. As Marçal notes, describing her experience of working on Ten Years Alive after his death, ‘Conrad’s absence made him ever more present’.

Knowing this about Conrad led us to ask a series of questions. What are we to make of the loss of Conrad’s dynamic presence as the teacher and instigator of Ten Years Alive? What do these two roles consist of, and what account is needed for us to fully understand them? Who or what can step in to fill these gaps? What relationships needed to be sustained or created in order to conserve and perform the work in Conrad’s absence? Through confronting these questions our research showed how conservation activity is not solely the domain of conservators. With works like Ten Years Alive, where the skills required go beyond those of material maintenance and repair, the conservation of the work becomes an endeavour that is widely shared through the various networks that surround it.

Multiple networks and shared authority

As we have seen, Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain is surrounded by people and practices which support and enable its continued performance. Our research brought these many and various relationships to light, leading us to ask: what are the implications of bringing greater visibility to the social networks surrounding a work, and allowing these to inform the discourse and practices of collecting and conservation? How is authority held and shared within such networks, discourses and practices?

It is useful to consider the different networks around Conrad and Ten Years Alive as having defined stages and purposes. For example, there is the network that supported Conrad and his work while he was alive, the network that formed to take care of his legacy after his death, and the network that is created around this work as it extends to include the museum. Members of these different networks overlap and extend outwards both through the networks formed before and after the death of Conrad and through the ongoing intergenerational transmission of the work to new performers and future audiences. In so doing, they highlight the dynamic and fluid nature of the networks and of the work itself.

Fig.6

‘Transmitters’ Angharad Davies (left) and Rhys Chatham (right) sharing their experience of performing Ten Years Alive during the feedback session, Tate Liverpool, 15 May 2019

Photo: Roger Sinek

The relationships between those involved in previous performances of Ten Years Alive permeate both this case study and our wider work to understand how this performance has been learned and passed on while Conrad was alive, how it might continue to be performed after his death, and what might happen in the future. The first time I encountered Ten Years Alive it was clear that our ability to successfully bring the work into Tate’s collection was dependent on specific individuals within these networks: the wide variety of people who had for many years sustained the work and whose responsibilities had shifted and continued to change since Conrad’s death in 2016. These were the trusted group of ‘transmitters’ of the work, some of whom were already referred to collectively as the ‘cooks’ – a nod to their connection to the independent media space The Kitchen in New York, where the work was first performed in 1972. This network emerged over a long duration, starting with the invitation by Rhys Chatham to Tony Conrad to perform at The Kitchen, and connecting different people and places over the intervening years (fig.6). Many of these transmitters also had professional roles tied up with this work, for example as paid performers, archivists, sound engineers and producers. The network has been re-formed, and often extended, each time Ten Years Alive has been performed. While Conrad was alive, he mixed those who were friends, colleagues and collaborators with those who were new to the work and local to the venue in which it was to be performed, thus expanding this network.

After Conrad’s death, the authority shifted and was consolidated. Initially it lay with Conrad’s widow, Paige Sarlin, who was heavily involved in maintaining the legacy of Ten Years Alive, in particular through the 2017 performance at Tate Modern. The gallerist Vera Alemani, then working at Greene Naftali, which represented Conrad, also knew the work well and was instrumental in the early discussions with Andrea Lissoni and Tate. Those who held authority through having performed the work and having been close to Conrad included music producer Regina Greene; the original performer of the long string instrument, Rhys Chatham; the violinist Angharad Davis; and Andrew Lampert, artist, projectionist and archivist for the Conrad Estate – all of whom were involved in the 2017 Tate performance.32 Over the course of 2017–19, when the work was chosen as an area of research focus for the Reshaping the Collectible project and it was also agreed that the work should start its journey into Tate’s collection, shifts within the network surrounding Conrad continued. These were in part due to illness, other commitments that members of the network had in their lives, and new individuals coming into the picture who were not involved in the 2017 Tate performance but who knew Conrad and the work well. By 2019 Sarlin had stepped back, and the network had developed more formal structures, such as the formation of the artist’s estate headed by the artist Tony Oursler. David Grubbs, who had himself played the long string drone in a performance of Ten Years Alive in Chicago in 1996, supported Oursler and his assistant Jack Colton in their work to fabricate a new version of the instrument. Grubbs tested the newly made long string drone before it was shipped to Tate and made a video to explain how it is tuned and played.

As is documented in the present publication, the Reshaping the Collectible project team contacted other individuals who had performed the work and also engaged new performers to perform it at Tate Liverpool. The research team and time-based media conservation team at Tate also worked with the estate and transmitters of the work to produce the dossier outlining information to help inform future performers and producers of the work.33 As explored in ‘Experimenting with Transmission’ by Marçal, Lawson and Ribeiro, and in Marçal’s essay ‘Ecologies of Memory’, these new performers, brought on board to perform the work for the first time in 2019, have also become potential transmitters of the work to other performers in future, thus continuing to extend the networks surrounding Ten Years Alive.

Over the course of our research it became clear that acknowledging these various networks required a shift in the way in which we think of works coming into the collection at Tate. Instead of the work being slowly engulfed by the museum, the museum team were joining an existing set of networks into which we had been invited. This balance of care and authority was central to this research, and, as will be shown below, it figures in each of the papers in this publication in various important ways.

Networks and ecologies

In considering the nature of the networks that are so instrumental in the transmission of Ten Years Alive, it is worth pausing to consider two terms used within this publication, namely ‘network’ and ‘ecosystem’ or ‘ecology’. While these terms are not to be considered as binary opposites, they do have different connotations.

Networks are dynamic, purposeful, able to extend and grow. The interdisciplinary theorist Maria Puig de la Bellacasa also points to how networks draw connections between one point and another, and it is through these connections that agency flows; however, while networks distribute power and agency, they do this unevenly.34 The use of the term ‘network’ in our research and in this publication acknowledges that the group engaged in the legacy of Conrad’s work is both purposeful and somewhat exclusive. It is purposeful because it is committed to continuing to support Conrad’s work and reputation, and therefore has clear goals. Yet it is exclusive because authority is established largely through the experience of having worked with Conrad and having been close to him, the number of times a person has performed a work, as well as their expertise, reliability and level of engagement.

The network surrounding Ten Years Alive grew while Conrad was alive through his teaching the work to others, and now that the work has entered Tate’s collection, the museum seeks to extend the network to include new performers in the hope that they, too, can act as transmitters for the work in the future. The bridge between the museum and the previous network that had formed around Ten Years Alive was the curator Andrea Lissoni, who had produced the work at the Live Arts Festival in Bologna in April 2013. Lissoni had come to know Conrad, and then shortly before Conrad’s death had gone to talk to him and his then gallerist Vera Alemani about the possibility of this work coming into the collection. Both Lissoni and Alemani were therefore important instigating forces within the reconfiguration of this network. When the work was first considered for Tate’s collection in 2016 this triggered the museum’s licence to care, impacting the existing network to form a new, modified one that included the museum and its staff.

A network is dynamic, and we see this in the networks surrounding Ten Years Alive, where there have been shifts in power during and after the death of Conrad. Judgements regarding the standing of those in the network, as well as the desire of individuals to step forward or step back from roles within it, create dynamic moments of inclusion and exclusion as the influence of those who are part of the network shifts.

The second key term used in our research and in this publication, that of an ‘ecosystem’ or an ‘ecology’, is useful in drawing attention to the interdependencies between the different agents surrounding Ten Years Alive – both people and things – and how the roles of these agents might change and circulate. These might be individuals or tools, such as the ‘dossier’ created for the transmission of Ten Years Alive; or the impact of substituting Conrad’s live violin part, with all his charisma as a performer, with a recording of him playing a section of the piece that is then made into a loop. Unlike a network, which is purposeful and exclusive, nothing is irrelevant within an ecosystem. The notion of an ecosystem also points to the wider ecology of the art system and the experimental music world that includes galleries, festivals, museums, arts and performance venues, collectors, performers, producers and critics – which, as Marçal argues, represent the ‘ecologies of practice’ of which Ten Years Alive is a part.

Presenting the research

In her paper ‘“Yes, But How Can It Be Live and Collectable?”: Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain 1972’, Lucy Bayley provides a detailed description of the artwork’s biography through the fourteen different performances of the work that took place before it was acquired by Tate, and before became ‘abstracted from the body of the artist’. She examines whether the authority of the work is collectively shared or whether it has instead transferred fully to Tate now that Ten Years Alive has been acquired. Referencing the work of Rebecca Schneider and Fernando Domínguez Rubio,35 Bayley examines the different drivers, shaped by people and contexts, towards stabilising the identity of the work and the history of its variability. Using archival material, ethnographic methods and interviews, Bayley traces the changes through different performances in order to situate these within various trends in an expanded understanding of curatorial practice in the sixty years since Ten Years Alive was created. She outlines the messiness of the work’s history by charting the different ways in which when Ten Years Alive was revisited within the contexts of theatres, museums, expanded cinema, festivals and contemporary art venues, and the impact this has had on the perception of the work. Making visible the tensions between fixity and variability in the life of Ten Years Alive, Bayley asks whether a future for the work could involve building on and adding to the previous different iterations of its performance, rather than obscuring or repeating them. In Bayley’s view, this would prevent the work from being confined within the ‘circuit of its own history’, and would allow for a creativity in its future staging that still respects the artist’s legacy.

Fig.7

The new generation of performers using the dossier to perform Ten Years Alive in a closed session for the ‘transmitters’ as part of the research fieldwork, Tate Liverpool, 15 May 2019. From left to right: Catherine Landen, George Maund and Emily Lansley

Photo: Roger Sinek

In ‘Ecologies of Memory’, Marçal examines the challenges posed by a work which, as Marçal argues, was not designed to be performed without the artist. She builds on the work of memory studies scholar Andrew Hoskins, taking an ecological approach to memory studies to explore why works such as Ten Years Alive are so hard to conserve and how the museum can adapt its procedures so that works such this can thrive within it. Organised over four sections, the paper maps the memory ecology of Ten Years Alive through archival research, interviews with past participants and the production of new documentation. In this work Marçal finds that memories of the work are inextricably linked to interactions between Conrad and his collaborators. This dependency on intimacy and personal relationships with Conrad – particularly in the moments of planning for a performance, performing and rehearsing the work – is identified by Marçal as the fundamental difference between Ten Years Alive and ‘delegated’ performance works, which are not executed by the artist but by other selected individuals. Through her analysis Marçal concludes that in the absence of Conrad himself, performances of Ten Years Alive require both written and audiovisual documentation and the transmission of the work through people, affect and intimacy (fig.7).

Marçal also considers the question of whether the museum can promote new memory ecologies, referencing the work of Felix Stalder to explore how the digital mediation of Ten Years Alive provides access to several nodes of the work’s memory ecology in what Hoskins has called the ‘connective turn’.36 As highlighted above, Marçal explores Stalder’s idea of the ‘commons’, Viv Golding’s concept of the ‘affective museum’, and the feminist ethical framework of ‘affirmative ethics’ proposed by Rosi Braidotti to suggest a way in which the museum might move towards a position of the commons wherein it is simply another node in the artwork’s memory ecology, thus challenging such organisations’ power and neutrality.37 Marçal notes the small moves already made by museums towards this idea of the commons, but also highlights how far there is to go to realise it.