Explore the Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Rooms exhibition at Tate Modern. Hear from Tate curators Francis Morris and Katy Wan, as they explore the exhibition work-by-work.

Her Early Years

Kusama's family; Yayoi is second from the right Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

Yayoi Kusama was born in 1929, the youngest daughter of family from the mountainous region of Matsumoto in central Japan.

Her family made their living from the cultivation of plant seeds. There is still a plant nursery on the site of Kusama’s childhood home. She had a conventional upbringing, and when Kusama began to express enthusiasm in making art, her family were not wholly supportive. Her mother in particular discouraged her young daughter’s dreams of becoming a professional artist, trying to steer her instead towards the conventional path of a traditional Japanese housewife. But Kusama’s persistence was strong. When her mother tore her drawings away from her, Kusama made more. When she could not afford to buy art supplies, she used materials she found around the home.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Kusama, like other school-age children in her hometown, was called upon to work for up to twelve hours a day in a parachute factory. Despite this punishing work, she managed to find the time and the resources to continue drawing.

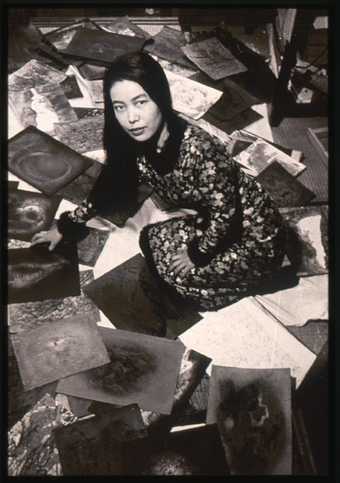

Portrait of Yayoi Kusama in her room in her parents’ home in Matsumoto, c.1957 Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

Kusama began publicly exhibiting her work in group exhibitions in her teens and in 1948, after the War’s end, Kusama convinced her parents to allow her to go to Kyoto to study painting in the Japanese modernist Nihonga style. She continued her studies in Kamakura City but soon grew tired of the conventional approaches of her teachers. Her great ambition and talent were recognised when she began staging solo exhibitions in her home town in the early 1950s.

Kusama’s achievement as a woman artist, coming as she did from a traditional background in a conservative part of Japan in the early part of the twentieth century, cannot be underestimated. It was her own drive and confidence in her talent that enabled her extraordinary career.

Kusama standing in front of Lingering Dream, selected for the Second Creative Arts Exhibition in Nagano, 1951

Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

Kusama's third solo exhibition – her first in Tokyo – at the Shirakiya department store in Tokyo, 1954

Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

Kusama and Fashion

Kusama has always had an interest in self-presentation, and her photographic archive shows how much she has enjoyed finding a personal ‘look’ to suit each body of work. Even today, Kusama still displays her keen and unique fashion sense.

In her early years in the United States, Kusama dressed formally for her private views and wore kimonos she had brought from Japan. She periodically returned to this Eastern style of dress. In 1966 Kusama made her slide work Walking Piece. The artwork records the artist walking through New York in a pink flower-print kimono. In this piece Kusama self-consciously uses the kimono to position herself as a creative outsider in the middle of an unfriendly, alien city.

More typically during this period, however, Kusama displayed herself in Western clothes that complemented the work she was producing. We can see how her style of dress changed from the prim, monochrome suits and dresses she wore with her similarly stark, monochrome Infinity Net paintings, to the red leotards and catsuits she wore in her red-and-white installation Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field.

© Yayoi Kusama/ Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

Kusama with Zoe Dusanne at Dusanne Gallery, Seattle, 1957 Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

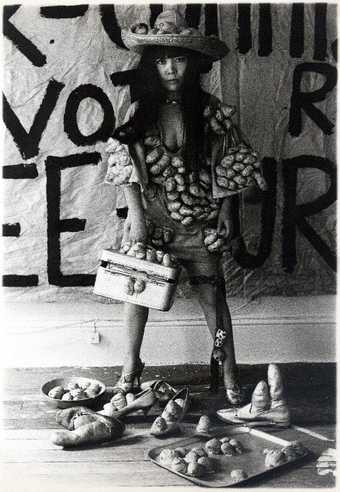

In the late 1960s Kusama set up her own fashion company. Many of the clothing designs were daring and featured strategically-placed holes which revealed the wearer’s breasts, buttocks or genitalia. For her Homosexual Wedding performance in 1968, she designed an ‘orgy’ wedding dress for two people. By 1970 she was producing similar garments that could accommodate several people. For herself she designed a Phallic Dress, its bright pink surface enhanced by numerous sewn stuffed fabric phallic bumps.

In recent years Kusama has continued to design her own clothes, using patterns from her paintings on bespoke fabric. She often complements her outfits with brightly coloured wigs to complete the distinctive ‘Kusama look’.

Kusama and anti-war activism

Yayoi Kusama Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization) 1950

© Yayoi Kusama Kusama Studio, Inc. Collection: National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Yayoi Kusama has always had a strong political conscience. Some of her earliest surviving paintings relate to the horrors of war: Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization) and Earth of Accumulation, both dating from 1950, show bleak, war-torn landscapes where even plant life struggles to survive.

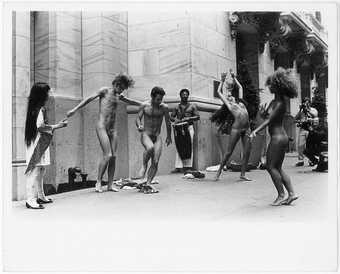

In the 1960s, during the Vietnam War, Kusama staged demonstrations in New York. These events counteracted violence with activism in the form of naked body painting happenings and love-ins. Her first Anatomic Explosion featuring naked dancers took place on 15 October 1968 opposite the New York Stock Exchange. The artist's press release stated, ‘The money made with this stock is enabling the war to continue. We protest this cruel, greedy instrument of the war establishment.’

Yayoi Kusama Anatomic Explosion on Wall Street 1968 © Yayoi Kusama/Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc

Yayoi Kusama Revived Soul 1995 © Yayoi Kusama/Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc. Collection: Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art

Later that year Kusama produced An Open Letter to My Hero, Richard M. Nixon in which she wrote:

Our earth is like one little polka dot, among millions of other celestial bodies, one orb full of hatred and strife amid the peaceful, silent spheres. Let’s you and I change all that and make this world a new Garden of Eden…. You can’t eradicate violence by using more violence.

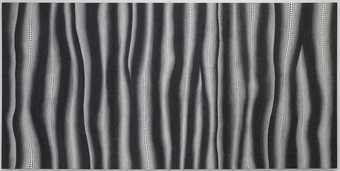

Later, on her return to Japan, Kusama made a series of anit-war collages. War, Tidal Waves of War and Graves of the Unknown Soldiers feature harrowing images from news magazines overlaid with watercolour and pastel. In 1995 Kusama responded to a commission from the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art to produce a new work commemorating the victims of the atomic bomb. She responded with the large-scale triptych Revived Soul. Unusually for the artist’s work of the period, the painting is drained of colour, featuring abstracted waving vertical bands of black and white that suggest a forest of dead trees, all covered in her signature polka dots.

Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room-Phalli’s Field 1965 © Yayoi Kusama

Five minutes with Yayoi

We catch up with Kusama, about her work, her wardrobe and last night's dinner ...

1. What did you have for dinner last night?

I had a bowl of fresh vegetables and egg soup for dinner.

2. What is the most meaningful thing you’ve ever produced?

It’s art. I started creating art works at the age of 10. I’ve worked very hard as it is my calling. I’ve struggled and devoted all my energy to artistic creativity and its excellence with a feeling of awe.

I fight to find love and a mystery of human life.

3. Why environmental art?

I’ve always experimented various expressions in art. Among them I especially put my heart and soul into environmental art. My art is not only with paper and a brush but the world I see is endless space. I create environmental art to prove great spirit of inquiry in the diverse human history. It is environmental art that I could devote all my efforts to as a way to seek for truth with all my heart.

4. What are you wearing today? What inspired you to wear it?

I’m wearing my working clothes. Not only working clothes but also all my clothes including my pajamas are all stained with paints.

5. What’s next for Yayoi Kusama?

I’ve sought for truth of art with an ambition and fought like hell all my life to accomplish my purpose as a human being. Even after I finish my life, I’d like to keep telling posterity about my way of art. I want younger people, or everyone, to talk about my enthusiasm reaching to space and also, my art as a token of my life even after my death. For that reason, I worked all this morning. I’d like to keep creating art until the day I die.