Editor’s note

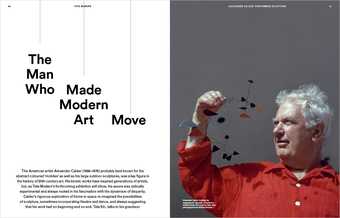

Paris 1931, and the young British artist Julian Trevelyan is enjoying a riotous life amid the European avant-garde. He is trying out his skills at his friend Bill Hayter’s print studio Atelier 17, also used by Miró, Max Ernst and Giacometti, while the neighbour in his studio block on the Villa Brune in Montparnasse is the American artist Alexander Calder. Here, Trevelyan would witness the evolution of Calder’s kinetic works, describing what he saw as ‘complex systems, cranks, cams and little balls swinging on the end of wires’. Some of these sculptures went on display that year at the Galerie Percier, and you can also experience many of the works themselves at Tate Modern’s forthcoming Calder retrospective, including a mobile now in Tate’s collection that Trevelyan bought from the artist.

As Trevelyan writes in his memoir Indigo Days, Calder would invite his friends to see a performance of his (now legendary) circus. Benches would be arranged around a small green baize circle in his studio, and they would sit there ‘cracking peanuts to the music of Sousa’. Calder would then produce his cast of characters from an old suitcase, ‘his wire acrobats, the tightrope walkers, the sword-swallower Eesgotten Ironguts…’ Trevelyan’s breezy descriptions underplay not only the radical and experimental nature of the work Calder was making, but also the effect it had on people (Trevelyan’s own drawings of the time feature wiry figures in motion). As Calder’s grandson Alexander S. C. Rower tells Tate Etc., his grandfather’s art had a great impact, not only on Duchamp, who was ‘bewitched by his innovations’, but on a generation of younger artists including Brazilians such as Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape.

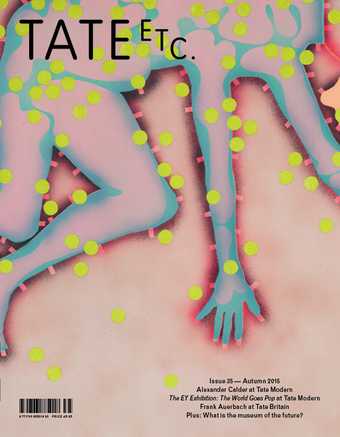

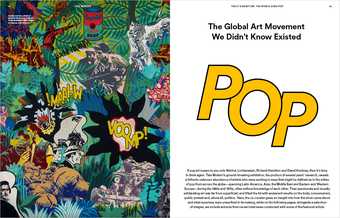

Will the artists in The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern have a similar effect? This ground-breaking show reveals many artists from across the world working in the pop genre, most of whose names you may not be familiar with, but whose art definitely deserves to be far better known, such as Jerzy Zieliński, Evelyne Axell, Cornel Brudascu, Marta Minujín, Keiichi Tanaami and Kiki Kogelnik (a detail of Fallout 1964 is on our cover). It is now clear that not all roads stemmed from American pop, and that there is no single strand of pop art. As the curators note, there are ‘many pops’ – the subversive, the political, the feminist and the commercially aware – that ‘are each complex and rich in their own right’. The show is full of revelations, so don’t miss it.