This paper explores the nature of the subjective aesthetic experience in which nineteenth-century visual artists were engaged when the sublime and music became twinned in their imaginations. This subjective experience is considered as an aesthetic response to the world and to the experience of being in the world. In nineteenth-century thought it became a way of perceiving that depended upon a certain understanding of music, which placed it apart and above all the other arts.1

Arguably, music can be seen as the ‘keynote’ to the sublime. The keynote of any piece of music is the fundamental tone to which music ‘resolves’. But by the 1890s, within British culture, the term had come to denote, more controversially, newness. This was due specifically to John Lane’s Bodley Head series called ‘Keynotes’, which, together with its companion series of books known as ‘Discords’, stood for literary tendencies that were consciously anti-bourgeois and relished the pejorative designation ‘decadent’. These John Lane books, by George Egerton (Mary Chavelita Dunne) and others, were constructed and received as challenging in their style and content, appearing to revel in displacing moral and literary certainties.

Just as the paradoxes and contradictions set up by such texts and the debates surrounding them identified double-edged ambiguity as a key characteristic of late nineteenth-century thinking, so, too, certain musical works, and the critical controversies they provoked, were crucial to contemporary reception of programmatic narrative arts. An ideological battleground between defenders of absolute music (instrumental compositions with generic titles or numbers, exhibiting purely musical methods and techniques of composition, for example, symphonies) and supporters of programme music (evocatively titled instrumental works with associations with other art forms and extra-musical experiences, emotions and sensations, for example, symphonic poems and opera) was established in the mid and later nineteenth century.

These differing perspectives have since permeated accounts of how musical style developed during the years when Romanticism became seemingly confused and exhausted.2

As tonality was regarded as entering into a state of ‘crisis’, newer music inevitably became classified as degenerate compared to the relative purity of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century classical canon. The contemporary commentator Max Nordau’s 1895 diatribe against contemporary culture, Degeneration, was typical in this respect, and his book became a classic compendium of the trends of his time. Recently, the renowned pianist and writer on music Charles Rosen has commented that Nordau’s claim that all modern art was ‘produced by moral degenerates’ is part of ‘perhaps [the] oldest continuing tradition’ of classical music. As the ‘displacement of one music by another’ is ‘an eternal part of history’, so complaints and laments about the loss of past perfections are an inevitable consequence.3

There was not necessarily more sublime music in the nineteenth century than later, but notions of the sublime were particularly significant in critical discussions then and informed artistic practice. Nineteenth-century musical enthusiasms are identifiable from concert programmes and the publication of salon music, as well as from reviews and references in novels. How far British taste connected to philosophical aesthetic thinking on the sublime can thus be assessed in the various ways in which contemporary musical compositions were discussed.

Felix Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture, also known as Fingal’s Cave, embraced the drive towards the programmatic and the narrative within early to mid nineteenth-century music, using the tonal idiom colouristically and atmospherically. Mendelssohn encountered the island of Staffa in a storm. The resulting music can be ‘read’ as drawing upon his experience of the island and its cave. The music recalls the amazing acoustics of the place with resounding crashing waves, a sense of powerful climax as the waves strike the cave in the storm, the rising and falling of the sea followed by moments of deep calm, and the soaring echoes of seagulls. This type of reading of the self back into nature is still current, and many commentators, particularly in notes about recordings, refer to the philosopher Edmund Burke’s passion for nature – astonishment, suspense of emotion, even horror in the awe with which body and mind are filled, revealing the listener, like the perceiver and like Mendelssohn himself, overwhelmed yet exhilarated. Writing of Mendelssohn’s musical landscapes, the academic writer Thomas Grey has dwelt upon the accepted ‘pronounced visual orientation to Mendelssohn’s cultural background’, that is, the fact that he was also an amateur artist. The influence of this exploration of visual art, Grey notes, has ‘long been perceived as an influence on his musical production’, and notably on the Hebrides Overture, which ‘evokes the heroic sublime tradition of Ossianic painting from the Napoleonic era’.4

For another recent writer Michael Steinberg who has made a study of the role of music in nineteenth-century cultural life, Mendelssohn’s music embodies aspects of the natural world yet constructs these into ‘a metaphoric landscape of inner life’. The Hebrides seems to set a physical scene, but its overriding musical power lies in its sweeping melody and thus its vision is of ‘absolute’ not ‘programmatic’ music. Just as a Romantic landscape is not merely a depiction of the external world but is ‘a way into inner nature’, so this work ‘engages a scene’ and ‘is born as music’.5

To Steinberg, the big melodic string theme liberates the music from mere mimesis; this melody functions dramatically in the work, as a musical not merely representational voice.6

The way that the work seems explicitly evocative of nature recalls discussion of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony (‘Pastoral’, 1808). As an expression of feeling about being in the countryside, rather than as an illustration of the rural, Beethoven’s symphony seems to go beyond the absolute into the realms of the programmatic: the emotions expressed are responsive to the experience of nature. The music depicts both a storm and the sensation of being in a storm. The genre of the symphony, an example of ‘absolute music’, was strongly associated with the sublime after the critic E.T. Hoffmann’s famous 1810 review of Beethoven’s Fifth. Hoffmann, who opposed programmatic music (and ignored the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony), appreciated the solemn grandeur of the heroic he identified in the Fifth, and referenced the ‘monstrous and the immeasurable’ and the ‘level of fear, horror, revulsion, [and] pain set in motion by Beethoven’s music’.7

The impact of the notion of the sublime within critical perception of music showed particularly in the privileging of the non-associative qualities of music. Hoffmann’s identification of sublime qualities became a key descriptor for expressing the impact of emotion in abstract terms. Although there is much ‘programmatic’ narrative music in the later nineteenth-century, ‘tone painting’ as a compositional technique was openly disparaged by many critics for whom abstract instrumental ‘absolute’ music remained the ideal.

Fig.1

J.M.W. Turner

Staffa, Fingal’s Cave exhibited 1832

Oil on canvas

908 x 1213 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

J.M.W. Turner’s painting Staffa, Fingal’s Cave (fig.1) was exhibited in 1832 and Mendelssohn’s overture was performed in London in the same year, a fact that has led to the two works being seen as linked historically.8

Many of Turner’s images show a tendency to dissolution and project the beginning of an abstract painterly aesthetic, which, according to Edward Lockspeiser and others writing about music and painting in the later twentieth century, can be seen as stemming from the aspiration to a musical state.9

Mendelssohn’s piece has tended to be categorised and valued as ‘music for music’s sake’, as absolute and not programmatic music. Lockspeiser, however, has seen in the work the beginnings of musical ‘impressionism’, referring to contemporary critical responses that spoke of the music’s veiled and blurred quality.10

Interestingly, in more recent times, a newspaper review of a performance of the Scottish composer Thea Musgrave’s 2005 Turbulent Landscapes, the second movement of which, ‘Shipwreck’, is a conscious homage to Turner’s Staffa, questioned the relevance of paintings for an appreciation of music, challenging the need for music to have any kind of associative ‘prop’.11

Towards the latter part of the nineteenth century, many artists and creative writers across Europe sought to depict sound and to capture the essence of music’s perceived mysteries, insights and truths. This tendency to ‘improvise’ with music’s non-imitative qualities and to enter into the ‘condition’ of music is expressed in the nineteenth-century writer and aesthetician Walter Pater’s essay ‘The School of Giorgione’ in Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) which set out to explore the interrelations of the arts. Pater did not seek a merger of all art forms within music’s keynote. ‘It is a mistake,’ he wrote, ‘to regard … all the various products of art as but translations into different languages of one and the same fixed quantity of imaginative thought’. And he went on to propose that ‘the sensuous material of each art brings with it a special phase or quality of beauty, untranslatable into the forms of any other. Each art … having its own peculiar and incommunicable sensuous charm, has its own special mode of reaching the imagination’.12

For Pater, music was more than a form; it was an artistic principle, one that sustained an ideal marriage of form and matter in the suspense of a perfect moment in which the subject and its expression ‘inhere in and completely saturate each other’.13

In such moments, he said, ‘life itself is conceived as a sort of listening’.14

In the second half of the nineteenth century music remained a Romantic art in an age dominated by positivism and realism. According to the academic Carl Dahlhaus who, writing in the 1970s, characterised the music of this time as ‘neo-romantic’, it was music’s ‘very dissociation from the prevailing spirit of the age’ that ‘enabled it to fulfil a spiritual, cultural and ideological function of a magnitude which can hardly be exaggerated.’15

For the nineteenth-century philosopher Schopenhauer, music remained above the positivism that connected art to the external through historical or environmental influences. Only music, he felt, was able to reveal absolute reality and ‘could in a sense, still exist even if the world did not, which could not be said of the other arts’, because ‘it is quite independent of the world of appearances’.16

In his 1870 essay on Beethoven the composer Richard Wagner, following the philosopher Schopenhauer, asserted that the category of the sublime was crucial for understanding music, declaring:

Surveying the historical advance which the art of Music made through Beethoven, we may define it as the winning of a faculty withheld from her before: in virtue of that acquisition she mounted far beyond the region of the aesthetically Beautiful, into the sphere of the absolutely Sublime; and here she is freed from all the hampering of traditional or conventional forms, through her filling their every nook and cranny with the life of her ownest spirit. And to the heart of every human being this gain reveals itself at once through the character conferred by Beethoven … on Melody, which has now rewon the utmost natural simplicity … Melody has been emancipated … and raised to an eternal purely-human type. Beethoven’s music will be understood throughout all time.17

Wagner’s essay revealed how for him music excited the highest of ecstasies such that by means of music it was possible to go beyond the self, into a state of boundlessness. The inner world, then, was the realm of the ear, which listened for the sublime; music became a form of revelation – a philosophy of deeply inward experience. For Wagner, music itself thus had a sublime calling.

The reputation of Beethoven remained colossal into the end of the nineteenth century, and it is significant that it was Beethoven’s music which gave rise to Wagner’s expression of characteristics of the sublime. The Ninth Symphony, particularly, was claimed by Wagner as a precursor of his own vision for the arts. Wagner’s work, like the music of Beethoven, was also simultaneously historicised and admired as modern by fin-de-siècle commentators.18

Premiered in 1865, his opera Tristan und Isolde had a massive impact, and, more than any of his other works, was responsible for turning him into a cult figure.19

Wagner was not only a composer but also a philosopher whose writings (translated into English in several volumes that appeared from 1892) set out notions of the ‘art work of the future’, and Gesamtkunst (the total work of art) that dominated new trends across the arts in the second part of the century. In ‘The Art Work of the Future’ (1849) and ‘Music of the Future’ (1860) he declared that the all the arts had a natural alliance, and that this alliance would serve to free both art and the artist to ‘the glad consciousness of his oneness with nature’.20

In Britain the cult of Wagnerism became particularly fervent in the 1890s, and ‘Tristanism’ took a strong hold. Tristan and Isolde set itself apart from Wagner’s other operas because it seemed to demand a private and personal response.21

The long drawn-out chromatic harmony served to slow time down, as if there was some kind of eternal hiatus springing from the love-making of the characters Tristan and Isolde. The music created a sensation of endless bliss surrounding the dying lovers. The opera was notorious for its overwhelming effects, and critical reception in words and other creative responses, such as illustration, fiction and poetry, emphasised the work’s striking modernity. The American critic James Huneker, whose books were published in Britain as well as in North America, declared Tristan and Isolde to contain ‘the seeds of the morbid, the hysterical, and the sublimely erotic – hallmarks of most great modern works of art’.22

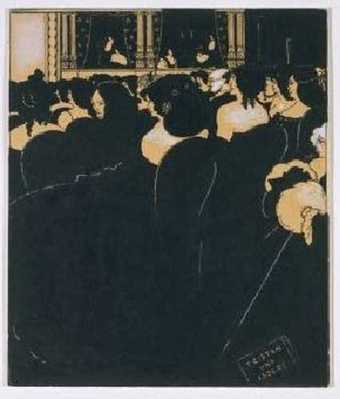

Fig.2

Aubrey Beardsley

Wagnerites 1894

Victoria and Albert Museum

© The Board of the Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum

Aubrey Beardsley’s depiction of women in an audience listening to Wagner’s music, Wagnerites 1894, suggests the interior gaze talked about by Schopenhauer and Nietzsche (fig.2). Music is internalised within the listener as exciting a purely private and silent experience, an intense physicalised response, with the music being worshipped as revelatory of ultimate truth. In her recent study of 1890s Wagnerism Emma Sutton asked of Beardsley’s image whether it was a representation or a critique of the erotic tension in a Wagnerian audience, or perhaps both, since Wagner’s work ‘was frequently – controversially – productive of introspective, solipsistic aestheticism’.23 This ‘erotic sublime’ was connected to a pre-Freudian idea of art as de-sublimating, as evidenced in the sexologist Havelock Ellis’s discussion in his 1898 essay, ‘Casanova’. For Ellis, Tristan and Isolde was an example of how modern art had taken over a role from Saturnalian orgies of earlier eras:

We have lost the orgy, but in its place we have art. Our respectable matrons no longer send out their daughters with torches at midnight into the woods and among the hills, where dancing and wine and blood may lash into their flesh the knowledge of the mysteries of life, but they take them to Tristan, and are fortunately unable to see into those carefully brought-up young souls on such occasions.24

Music was particularly important to the visions of the painter George Frederick Watts. In a recent re-assessment of the painter, the art historian Hilary Underwood has contextualised Watts’s musicalised art with the work of other aesthetic and symbolist painters to whom ‘music was the supreme art: non paraphrasable, non realistic, it conveyed profound emotion through its form.’25 From the late 1850s into the 1870s Watts was associated with a group of artists and writers around Rossetti and Whistler characterised by a desire to produce ‘art for art’s sake’. They aimed to communicate visually through what came later to be thought of as the ‘abstract’ means of line, form and colour, even when the human figure remained the basis. Pater’s ‘Conclusion’ to The Renaissance which speaks of the balance between the ‘desire of beauty and the love of death’, can be seen reflected in Watts’s Love and Death 1885–7 (fig.3), a work that became a key symbolist image after its first appearance in Paris.

English symbolist painters were drawn to the writings of the nineteenth-century French poet Baudelaire, also a Wagnerite, in this period. Baudelaire’s poetry and other writings became known in England by various routes, notably the admiration of the English poet Swinburne. Not only had Baudelaire developed a notion of synaesthesia in sympathy with Wagnerian ideals, which he called ‘correspondence’, but also he invoked a sense of the sublime in his reflections on the experience of listening to the music of Wagner:

When I heard it for the first time, with my eyes closed, feeling as though transported from the earth … I felt freed … and recaptured the memory of the rare joy that dwells in high places … Then, involuntarily, I evoked the delectable state of a man possessed by a profound reverie in total solitude, but a solitude with vast horizons and bathed in a diffuse light … Soon I became aware of a heightened brightness, of a light growing in intensity so quickly that the shades of meaning provided by a dictionary would not suffice to express this constant increase of burning whiteness. Then I achieved a full apprehension of a soul floating in light, of an ecstasy compounded of joy and insight, hovering above and far removed from the natural world … No musician excels as Wagner does in depicting space and depth, material and spiritual …He has the art of rendering … all that is excessive, immense, ambitious in both spiritual and natural man. Sometimes the sound of that ardent despotic music seeks to recapture for the listener, against the background of a shadow torn asunder … the vertiginous imaginings of the opium smoker … I had undergone a spiritual … revelation. My rapture had been so strong, so awe-inspiring, that I could not resist the desire to return26

Fig.4

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Veronica Veronese 1872

Oil on canvas

1092 x 889 mm

Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935

In seeking alternatives to narrative descriptive painting several British artists from the 1860s onwards used music to suggest new subjects and compositions, and, in particular to explore femininity. Whilst not overtly addressing the sublime, the art historian Suzanne Fagence Cooper has reflected upon the ‘trance-like state often associated with musical images’, considering, for example, the ‘rêverie produced by listening to music’ as a key aspect of sensuality in Rossetti’s Veronica Veronese 1872 (fig.4).27

Here a female musician is seen not as a passive listener but as an artist within a creative process, in a state of absorption: Rossetti himself called this a ‘musical painting’. His observations about listening in pictures and poems reveal his involvement with music as lived experience, in a way which extended the Romantic tradition.28

In her study of Rossetti and song, the writer, Elisabeth Helzinger has recently suggested that Rossetti explored listening visually and poetically because of his intellectual fascination with the effects of the listening, paintings and poems being the means ‘in which aesthetic cognition and creation itself could be studied.’29

Images of women with musical instruments were a feature of Rossetti’s later works. In La Ghirlandata 1873, for instance, female allure is associated with music, specifically a harp. Echoing this connection, in ‘Two Fine Flowers of Celticism: Encores’ (1897), Israfel, the aesthetic writer Gertrude Hudson, used a painter as protagonist in the story to explore musical experience as a form of ecstasy. Losing ‘consciousness with the thought of music’, the fictional painter goes to Tristan and Isolde for inspiration. ‘As he heard the divine first orchestral sighs of “Tristan”, he shivered – they held a spirit. As the music rose, passion of love, passion of death, he saw the face, the mouth of music. His soul dilated’.30

His resulting work was a portrait of music, a ‘languishing Orpheus’ represented as a woman, because ‘music is feminine’ and because ‘music became his only picture.’31

Was Watts’s Hope (fig.5), with its despairing central female figure and one-stringed lyre, being evoked here?32

Or was it Simeon Solomon’s painting and Swinburne’s commentary on his musical works which were being called to mind for turn-of-the-century readers?

The painter Whistler’s aspirations to musicality were articulated in the musical designations, such as symphony and nocturne, which he experimented with in the titling of his works. In the 1850s Whistler was a member of the painter Gustav Courbet’s circle in Paris, a group that included Baudelaire and Gautier who encouraged him to explore art in musical terms. Baudelaire’s remark that the ‘right way to know if a picture is melodious is to look at it from far enough away to make it impossible to understand it subject or to distinguish its lines’ is indicative of this.33 As a result of hostile criticism of Whistler’s painting (that involving the critic John Ruskin in particular), the association of the term ‘musical’ with ‘painterly’, as opposed to ‘literary’, was consolidated. Whistler’s titles signified that, for him, colour relationships had become abstract rather than mimetic, and that the qualities of tone, line and shape were tools for communication of subjective states.34 What Whistler wanted his viewers to do was not to read narrative into the paintings, but to feel the beauty and harmony of the colours and tones. Art could not deliver emotions or ideologies, according to Whistler. Art should appeal only to the artistic sense, not to emotions like love or patriotism; paintings were to be evocative like music.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Silver - Cremorne Lights

(1872)

Tate

Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Cremorne Lights 1872 is Whistler’s most empty of the night-time London paintings (fig.6). The composition’s subtle harmonies are intended to convey a state of mind. From 1872 Whistler started to re-title past works in order to emphasise their tonal qualities and de-emphasise the narrative content. At this time audiences for art were becoming attuned to these comparisons, led by their reading of critics who were contributing more than merely aping fashionable musical terminology. The theme of musicalised art became a dialogue between artists and critics.35 Were Whistler’s paintings ‘modern’ in the way they sought to suspend meaning? If aesthetic pleasure, rather than emotion, was Whistler’s understanding of the sublime, do his works defer resolution, like atonal music or even abstract painting? The disguising, even masking, associated with Whistler’s works is enhanced by the element of mystery provided by his musical titles. The critic Arthur Symons writing in Studies in Seven Arts (1906) suggested that Whistler’s works opened up the potential of art to the perceiver in a new way, because the paintings seemed to approach the viewer, rather than the viewer approaching the painting. Symons’s opinion appears inspired by Walter Pater yet embodies almost a postmodern sense of spectatorship: ‘Look around a picture gallery, and you will recognise a Whistler at once, and for this reason first, that it does not come to meet you. Most of the other pictures seem to cry across the floor: “Come and look at us, see how like something we are!” Each out-bids his neighbour, promising you more than your money’s worth. The Whistlers smile secretly in their corner, and say nothing. They are not really indifferent; they watch and wait, and when you come near them they seem to efface themselves, as if they would not have you even see them too closely. That is all part of the subtle malice with which they win you. They choose you, you do not choose them.’36

In The Lute of Apollo (1896) the reciter and writer Clifford Harrison suggested ‘there is a more interesting line of thought in the acknowledged association of colour and music than the development of a possible new art. It lies in the idea that – in some mysterious way … music and colour are in reality one and the same thing; that they are capable of transposition and interchange; and possibly possess, to some unknown but conceivable percipience, a unity – in sound that is seen and colour that is heard.’37 There are many examples of early twentieth-century composers who explored colour, both literally and metaphorically. Just before the outbreak of World War One, Scriabin’s Prometheus: Poem of Fire (1911) was played in successive years in London.38 This massive orchestral work featured an unusual use of choir, a four-part ensemble who vocalised on specific vowels with occasional ‘aspirate’, and attempted to express philosophical and theosophist ideas in music. It was seen as a natural progression of Wagner’s idea of a Gesamtkunst, and musically it developed late Wagnerian chromaticism and experiments with atonality. In Prometheus a ‘mystic chord’ made up of fourths permeates virtually the whole piece, and is treated like a tonal centre, that is, not as a discord seeking resolution, but the fundamental tone of the piece. The Promethean focus here links back to Beethoven’s The Creatures of Prometheus about the creation of mankind, and to the Romantic enthusiasm for the Titans’ rebellion against the gods. Scriabin said: ‘I am inclined to ascribe the enthusiasm for my Prometheus in England not so much to its music as to its mysticism’.39 An interesting example of the impact of Scriabin on British art, Duncan Grant’s Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914 (fig.7) was inspired by the colour-music dynamics and the media interest in the ideas behind the composer’s work.40

In his essay on ‘The Art Work of the Future’ Wagner used the sea as an extended metaphor for music, speaking of a sea of harmony and referring to the attraction of the depths: ‘Man dives into this sea … His heart feels widened wondrously, when he peers down into this depth … whose seeming bottomlessness thus fills him with the sense of marvel and the presage of Infinity’.41 There are resonances of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde with its sailing voyage and tragic plot, in Delius’s Sea Drift, composed in 1903–4, which confronts sublime tropes of mortality, loss and death through a musical seascape bounded by a profound sense of solitude. Furthermore, there is a connection to British visual artists’ fascination with seascapes and Turner’s immersion in the waters of the nautical sublime. Delius’s work is far from being merely representational of nature; an emotional response to the sea lies at its core. Its pantheistic pessimism reveals the influence of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Towards the end of Sea Drift, the bonding of a boy and a sea-bird almost becomes apocalyptic, expressing a moment of sublimity when the gull-cries become the boy’s cries as he sings ‘High and clear I shoot my voice over the waves’. And in Delius’s 1899 ‘Song of the High Hills’, the opening descending strings awakened the despair of the lowland, whereas the higher plane was conveyed by use of a wordless chorus in the section ‘The Wide Far Distance – The Great Solitude’ to suggest transcendent and non-human powers. The musicologist Christopher Palmer has striven to capture what for him lay at the heart of Delius’s aesthetic, describing this as the sensation of being suddenly gripped in a nocturnal setting by distant and unseen voices sounding from across the landscape – poignant and distant sounds expressing undefined longing and Weltschmerz.42 In another ‘religious’ and pantheistic work from the same year, the Mass of Life, the rarity of high places where the ego dissolves and is sublimated in the natural is expressed by Delius in a chromatic harmony derived from Tristan and Isolde and through the Dionsyian celebrations of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, the dancing superman. There are also parallels between Delius’s vision and the early twentieth-century experiments of Scriabin, with his proposed multi-dimensional total work of art ‘Mystery’.

In the same period in which he observed anaesthetised Wagnerite matrons, Beardsley also illustrated Oscar Wilde’s play Salome. Wilde’s symbolist reading of the biblical story of the femme fatale dancer was transplanted to the field of music with Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera, first performed in London in 1910. Wilde had written his play when Egerton had been writing Keynotes. Her story from that collection, ‘A Cross Line’, concerns the apparent liberation of an unnamed woman with a fetishistic need for attention indulging in a fantasy dance with snakes. Similarly, for the character Salome, a dominant figure across the turn-of-the-century arts – unlike the more anonymous and communal Wagnerite audience – participation in the ecstatic sublime was a public exhibition of out-of-control delirium resulting in murder. There seems here to be a relationship worth exploring between what happens to the feminine as it encounters the sublime and the ways that by the early twentieth-century musical language was characterised. Was atonal, colouristic and highly-textured ‘painterly’ music veering into the abyss of abstraction, chaotic and disorderly like the female; was it merely strange and exotic in its decadence; or was it rather a new ‘modern’ sense of art which was slowly liberating itself from romantic shackles?

The comparative cultural historian Brad Bucknell has recently commented that ‘the move towards music seems part of a tension within modernism itself which seeks both to abolish and preserve its romantic past at one and the same time’.43

And the art historian Karin von Maur has explored examples of twentieth-century painting which employ music as image, technique and metaphor, as a means of challenging existing artistic practices.44

For the writer and arts critic Christopher Butler, what defines a work as modernist ‘is not just the loyalty of its maker to the aesthetic of an evolutionary or disruptive tradition … but its participation in the migration of innovatory techniques and their associated ideas’.45

The sublime in music, the sublime and music, are within that ‘changing framework of ideas’ or ‘conversation’ among artists and critics which formulated subjective concepts to articulate and inspire stylistic change in modernist work in all the arts, work which in turn both conspired with and provoked audiences.46

Understanding the contemporary taste for particular sorts of music, how that taste was defined and notions of what music itself signified, and to whom, are meaningful to any discussion of thinking about the sublime in the later nineteenth century. The topos and techniques of music, explored in and through painting, delineated the sublime itself as a concept in the control of the receiver as much as the creator of art.

Today, the term ‘sublime’ has been and continues to be applied widely and enthusiastically to musical works of diverse character and genre.47

In common usage, it is applied where the experience of a work has any kind of overwhelming impact upon an individual.48

Postmodern theory has defined this impact as dealing with what lies somehow ‘beyond’, using concepts which embody absence – the unknown, the unspeakable, the unthinkable. This terminology is not so far removed from earlier conceptualisations, although it appears more tinged with negativity than the ecstatic language of previous centuries. In the catalogue for the end-of-the-twentieth-century Arts Council touring exhibition Sublime: The Darkness and the Light (1999) Jon Thompson stated that: ‘While traces of “sublime” experience are to be found in the art and literature of almost every period, the aesthetic category of “the sublime” as we know it today, was essentially an invention of the late eighteenth century’.49

There are, he comments, typical sublime subjects, but it is not works themselves which can be named ‘sublime’, rather, that the experience of the sublime can be re-presented in art works and consequently the receiver can gain access to sublime experience. Recently, for example, the contemporary philosopher Aaron Ridley, has expressed his conviction that empathetic response to music remains valuable, saying, ‘A state of soul … can be expressed in music – the state of a persona constructed in the musical experience of a responsive listener’.50

The eighteenth-century emphasis on individual aesthetic response as autonomous experience, thus, connects to the recent postmodern re-articulation of the subjective. The postmodern sublime carries a similar desire for the human to overpower the natural as had been expressed by the eighteenth-century philosopher Kant, and demonstrates a belief that an individual might, through such an experience be able to merge with the universal. This is how Judy Lochead conceives of it in a 2008 debate with James Currie concerned with ‘Theorizing Gender, Culture, and Music’. Lochead points out the consequences of the continuing polarisation of the beautiful and the sublime, because of the association of the beautiful with the feminine and the gendering of the nature of knowledge which continues to privilege the dominance of ‘concepts that are contrary to the philosophical and political goals of feminism’.51

This is a concern in relation to nineteenth-century music history because of the way that the philosophical expression of the notions of the beautiful and the sublime became gendered in the reception of music.52

The various re-inscribings of meaning by successive generations of listeners went largely unchallenged until late twentieth-century re-readings. Lochead and Currie have both showed concern that the concept of the sublime continues to be used in ways which retain what it sought to overcome, and that its use continues to avoid the construction of ‘a critical perspective on subjective aesthetic experience’.53

Recently Tate Liverpool’s website promoting its 2008 Gustav Klimt exhibition referred to the 1902 exhibition of the Secession as ‘a sublime realisation of the Gesamtkunstwerk in which the different arts … were united under a common theme.’54 In the late nineteenth century, although there were connections between the English Arts and Crafts movement and the Viennese secession, Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, which was made for the 1902 Secession exhibition, would barely have been known about in Britain. Built into the ‘gilded cabbage’ exhibition hall in Vienna, it could not travel. For Tate Liverpool’s major retrospective it was considered sufficiently important a work to be reconstructed. Today in Britain, Klimt’s work, which was inspired by Wagner’s response to Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’ from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, provides perhaps the supreme example of how musical art linked the nineteenth-century idealisations of the sublime to the avant-gardism of the Austrian Jugendstil magazine Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring).

Klimt is now one of western art’s best known and most commercially valued artists. His Beethoven Frieze consists of a series of panels that together create an impression of a temple to art. The perceiver is compelled to participate interactively with the work by moving around it, and to view it in conjunction with other related exhibits honouring Beethoven. The staged narrative of the painting depicts the Arts fulfilling a yearning for happiness, symbolised by five women who lead the perceiver or listener into an ideal state. Poetry is a woman playing a lyre; and the final image is erotic – an angel choir and a couple welded and wedded in a kiss. The ‘aspiration’ to musicality spoken of by Walter Pater, so influential in the late nineteenth century, can now be accessed very explicitly by means of the accumulated knowledge and reputation of Klimt’s work. Thus, the state of being in music and the imbuing of the self with the spirit of music found in Klimt’s images enable re-reading of the history of the sublime in and around nineteenth-century music to continue.