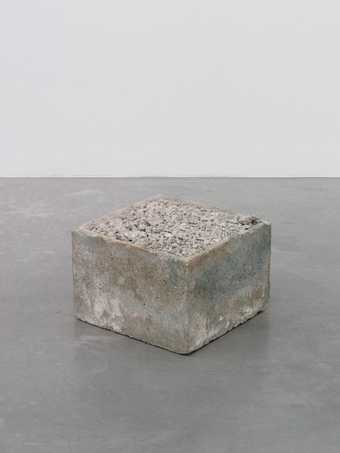

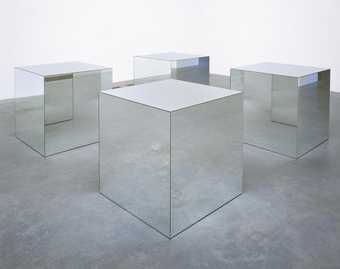

Robert Morris

Untitled

(1965, reconstructed 1971)

Tate

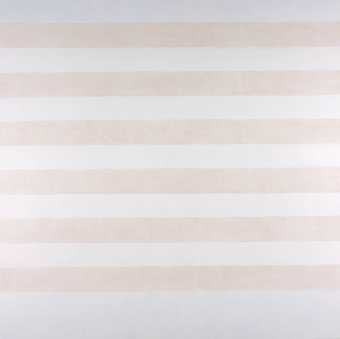

Minimalism or minimalist art can be seen as extending the abstract idea that art should have its own reality and not be an imitation of some other thing. We usually think of art as representing an aspect of the real world (a landscape, a person, or even a tin of soup!); or reflecting an experience such as an emotion or feeling. With minimalism, no attempt is made to represent an outside reality, the artist wants the viewer to respond only to what is in front of them. The medium, (or material) from which it is made, and the form of the work is the reality. Minimalist painter Frank Stella famously said about his paintings ‘What you see is what you see’.

The development of minimalism

Minimalism emerged in the late 1950s when artists such as Frank Stella, whose Black Paintings were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1959, began to turn away from the gestural art of the previous generation. It flourished in the 1960s and 1970s with Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin and Robert Morris becoming the movement’s most important innovators.

The development of minimalism is linked to that of conceptual art (which also flourished in the 1960s and 1970s). Both movements challenged the existing structures for making, disseminating and viewing art and argued that the importance given to the art object is misplaced and leads to a rigid and elitist art world which only the privileged few can afford to enjoy

Qualities of minimalist art

Aesthetically, minimalist art offers a highly purified form of beauty. It can also be seen as representing such qualities as truth (because it does not pretend to be anything other than what it is), order, simplicity and harmony.

Read the image captions of the artworks below to find out about some of the key qualities of minimalist art:

Sol LeWitt

Two Open Modular Cubes/Half-Off

(1972)

Tate

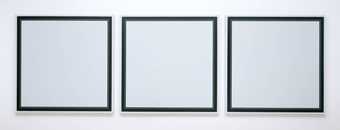

Donald Judd

Untitled

(1972)

Tate

© Donald Judd Foundation/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2024

Carl Andre

144 Magnesium Square

(1969)

Tate

Minimalism and early abstraction

Although radical, and rejecting many of the concerns of the immediately preceding abstract expressionist movement, earlier abstract movements were an important influence on the ideas and techniques of minimalism. In 1962 the first English-language book about the Russian avant-garde, Camilla Gray’s The Great Experiment in Art: 1863-1922, was published. With this publication, the concerns of the Russian constructivist and suprematist movements of the 1910s and 1920s, such as the reduction of artworks to their essential structure and use of factory production techniques, became more widely understood – and clearly inspired minimalist sculptors. Dan Flavin produced a series of works entitled Homages to Vladimir Tatlin (begun in 1964); Robert Morris alluded to Tatlin and Rodchenko in his Notes on Sculpture; and Donald Judd’s essays on Kazimir Malevich and his contemporaries, revealed his fascination with this avant-garde legacy.