Fig.1

Organisers of the First Russian Art Exhibition, Berlin, which opened on 15 October 1922

From left: David Shterenberg, head of IZO, D. Maryanov, representative of the Russian security services, Natan Altman, Naum Gabo and Friedrich Lutz of the Galerie van Diemen. In the foreground is the lost iron version of Gabo’s Constructed Torso 1917.

© Nina Williams

There has been a tendency in art-historical scholarship to regard Naum Gabo as a right-wing Russian émigré.1 In part, this is based on the assumption that an artist who left revolutionary Russia and ended his life in capitalist America during the Cold War was probably fairly reactionary in politics. Yet from studying the archive of Gabo’s papers, including his diaries and letters, and scrutinising the evidence in more detail, a very different and more nuanced ideological picture emerges.2

As I hope to demonstrate, Gabo was, in fact, a fairly radical figure during the years that he spent in Berlin from 1922 until he moved to Paris in 1933–4. Indeed, I shall argue that in Germany, Gabo continued to embrace the attitudes that he had acquired in revolutionary Russia in that he continued to espouse politically progressive, essentially pro-Soviet attitudes, to project an explicitly ‘internationalist’ outlook and to cultivate a wide circle of acquaintance from among a diverse range of nationalities. Although he was a Russian Jew from a fairly wealthy family, Gabo did not associate exclusively with any nationalist groupings, whether these were Russian or Jewish. Neither did he become close to any right-wing or reactionary elements. Instead, he identified with avant-garde elements whatever their nationality – German, Russian or Hungarian. At the same time, Gabo was concerned to establish international links with artists and institutions in France and America.

Gabo probably arrived in Berlin around the beginning of April 1922, and seems to have travelled to Germany in connection with the organisation of the First Russian Art Exhibition (Erste russische Kunstausstellung). In other words, he came to the West in a semi-official capacity, and in Berlin, therefore, would almost certainly have been seen as an employee or at least a representative of the Soviet regime. In one account of his departure, Gabo reported that David Shterenberg, the head of IZO Narkompros (The Department of Fine Art within the Commissariat of Enlightenment), had told him to go to Berlin, organise his work and be ready to help him.3 Gabo may also have received money to finance his journey and stay.4 When Shterenberg himself arrived in Berlin six months later, he apparently said to Gabo, ‘now you are here and will join my staff; [you will be paid] and will organise the three galleries of abstract art’.5 This is borne out by the ‘official’ photograph, in which Gabo appears alongside Natan Altman and Shterenberg (the two representatives of IZO), Marianov (an employee of the Soviet secret police) and Friedrich Lutz, who was responsible for the van Diemen Gallery’s new modern art spaces (fig.1).6 Gabo’s role in the exhibition is also confirmed by the reminiscences of the architect Berthold Lubetkin, who was responsible for collecting some of the works in Russia and installing them in Berlin.7

Gabo brought with him from Russia his creative archive – the essential ideas that he could work with further (that is, actual works as well as models, which could be developed or enlarged for sale or exhibition). Indeed, it seems likely that some works that were on display in 1922 might have been made in Berlin. The advantage of Gabo’s method of constructing sculpture from distinct pieces of material was that they could be collapsed, stored flat and so easily transported. He also had sketch drawings, which contained ideas for new works. Among his papers were some writings (including poems and short stories in Russian), as well as several copies of the Realistic Manifesto.8 In other words, Gabo brought with him the materials that would enable him to continue his creative life and to make his mark as a sculptor in this new environment. He does not seem, however, to have included photographs of works, documentation like the review of his Tverskoi Boulevard exhibition in 1920 or any art periodicals.

Thus, the archive suggests that Gabo was not merely envisaging a brief visit to the West like the poets Vladimir Maiakovsky or Boris Pasternak, but rather was intending to stay for a considerable length of time. On the other hand, there is no evidence that Gabo was intending to become a permanent émigré. There were, for instance, as far as we know, no personal photographs among his belongings. The photographs of Gabo’s Russian family among the artist’s papers seem to have come later from Alexei once Gabo re-established contact with his brother in Russia in 1959.

Whatever his original intentions, certain factors may have contributed to prolonging Gabo’s stay in Germany. Not least was the fact that he started to live with Elisabeth Richter in early 1923.9 She took him in and nursed him back to health after he had fallen seriously ill in spring that year. Gabo and Lisa continued to live together until she died in the late 1920s. With a private income, Lisa gave Gabo a measure of financial security as well as a settled way of life. They lived in a house in Lichterfelde, a respectable suburb of Berlin, where Gabo lived as a German, rather than as part of an émigré community. The fact that he had studied medicine, science, philosophy and art history at the University of Munich for four years before the First World War meant that he had a good grasp of the German language and culture.10 This was undoubtedly an asset in helping him to integrate into German life as well as the Berlin art world. It meant that he was not dependent on émigré networks for financial or social support.

Despite his domestic situation, Gabo was probably not contemplating permanent exile at this point. We know from the papers that Gabo subsequently brought out of Germany in 1933–4 that he did think about returning to Russia at certain times. In March 1928, for instance, his brother Alexei Pevsner, who was still living in Russia, wrote describing life in Moscow, the cost and availability of flats, and the artistic situation, including potential for commissions, in short the sort of information that would have been solicited by Gabo contemplating a return to his homeland.11 Two years later, Gabo was evidently thinking about re-establishing his career in Moscow, and he seems to have been considering going back as late as 1936.12 Even his decision to submit a design for the Palace of Soviets Competition in 1931 seems to have been based on an enduring attachment to his homeland and the desire to create an advantageous niche for his creativity in Russia, preparatory to his return.

The most revealing indication of Gabo’s position is the fact that he retained his Soviet passport until 1952, when he finally relinquished it in order to become an American citizen.13 This meant that he was free to return to the Soviet Union at any point. In 1934 Gabo was allowed to renew his Soviet passport in Berlin. He certainly would not have been able to do this if he had been involved with dubious groups or anything that had a whiff of being anti-Soviet, which would have included any association with radical political parties, including Communist parties that were not controlled by the Bolsheviks, as well as any right- wing or pro-Tsarist organisations.14 So, not only did Gabo continue to consider himself a Soviet citizen, but the Soviet Union also continued to acknowledge him as a Soviet citizen. In fact, when his daughter Nina was born in 1941, Gabo registered her at the Soviet Embassy in London, where she was added to his Soviet passport.

When Gabo arrived in Berlin he joined an enormous Russian émigré population. Between 1919 and 1923 the city absorbed a vast wave of emigration. At one point, 1,000 refugees were arriving every month, and by autumn 1920 there were over half a million Russians in Germany, and over 100,000 of them were living in Berlin.15 Marc Chagall, who also moved to the city in 1922, recorded his impressions: ‘In the apartments around the Bayerische Platz there seemed to be as many theosophical or Tolstoyan countesses talking and smoking around a samovar all night as there ever had been in Moscow … Never in my life have I met as many miraculous Hassidic rabbis as in inflationary Berlin, nor such crowds of Constructivists as at the Romanisches Kaffeehaus.’16

The writer Ilya Ehrenburg remembered how ‘at every step you could hear Russian spoken’,17 and noted Gabo’s presence at a memorable debate in late 1922:

There was a place in Berlin that reminded one of Noah’s Ark where the clean and unclean met peaceably; it was called the House of Arts and was just a common German café where Russian writers gathered on Fridays. Stories were read by Tolstoy, Remizov, Lidin, Pilnyak, Sokolov-Mitikov. Mayakovskii declaimed. Yesenin, Marina Tsevetayeva, Andrei Bely, Pasternak, Khodasevich recited poetry … A storm broke out at a lecture by the painter Pougny [Puni]; Alexander Archipenko, Natan Altman, Viktor Shklovskii, Mayakovskii, Gabo, El Lissitzky and I [Ehrenburg] argued furiously.18

Ivan Puni’s talk on 3 November 1922 had stridently criticised the impersonal character of geometric abstraction, while praising the more instinctive and personal art of Wassily Kandinsky.19 It is hardly surprising that Gabo, El Lissitzky and their circle reacted negatively. Gabo also recalled life in Berlin:

I remember we spent an evening with Elsa Triolet in 1923 in Berlin. Shklovskii Pasternak, and myself. There was a lot of talk … When I left, Pasternak left with me and I thought we would walk a little. But after our first few steps, Pasternak said ‘Gabo, lend me 5 marks’. I took out 5 marks and gave them to him. He quickly put them in his pocket and ran ahead. I never saw him again. He did not know that they were my last.20

These various memoirs suggest that Gabo was associating with Russians, but not with so-called white Russians or anti-Soviet émigrés, whom he referred to derogatively as ‘Balalaika Russians’.21 His friends and acquaintances tended to be innovative creative figures or members of the avant-garde like Shklovskii and Pasternak (who soon returned to Russia) and El Lissitzky, rather than more conventional creative figures.

Despite the fact that Gabo was born in the Pale of Settlement and his parents were Jewish, there is no indication that he had any extensive contacts with Jewish émigrés. He did not speak Yiddish – the main language of East European Jewry – and had not been brought up knowing even the rudiments of Judaism. He had never even attended a synagogue.22 At only two points in his early career had Gabo acknowledged his Jewish identity. The first instance was at the beginning of the First World War in August 1914, when he was a student fleeing Germany, and he and his brother Aleksei went to a Jewish organisation in Copenhagen, asking for funds to tide them over before money could reach them from their family in Russia.23 The second instance was when Gabo was starving in France in the mid 1930s and he made some photomontages for ORT – the Jewish Organisation for Rehabilitation and Training (fig.2).24

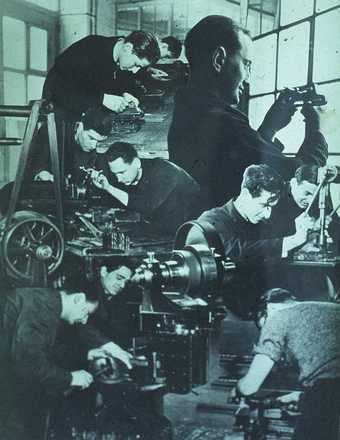

Fig.2

Naum Gabo

Photomontage for the Jewish Organisation for Rehabilitation through Training, known as ORT

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven

© Nina Williams

In Russia, Gabo had clearly identified with the Revolution – as an innovative artist. He was at pains to emphasise this in his subsequent writings and reminiscences. As a young man in the provincial city of Bryansk, he had reacted against social injustices and embraced the revolutionary cause. His memoirs written mainly in 1970s America confirm his earlier radical allegiances. He observed: ‘At the beginning of this century, in old Tsarist Russia, it was difficult for anyone born with a human heart and human feelings not to become a revolutionary. Only ossified blockheads remained insensitive to what was happening around them – the outrageous behaviour, cruelty and oppression of the “haves” towards the “have-nots”.’25

Not surprisingly, he reacted positively to news of the February Revolution in 1917 and subsequent developments. He had spent the years of the First World War in Norway and returning to Russia in spring 1917, he was electrified by the new spirit of liberty that was pervading the entire society. He later recalled: ‘The Revolution seemed to me to be some kind of heavenly radiance, a token of fate presaging a new life, a new earth, a new people in my homeland … I remembered my youth when the image of the Revolution was for me a golden dream … The Revolution was in me.’26 During the Second World War in Britain, when the fate of Europe and Russia seemed to be hanging by a thread, Gabo’s thoughts were very much directed towards his homeland and youth. He confided his reminiscences to his diary, including his recollections of the Revolution, asserting ‘I was one of the hundreds of artists in Moscow possessed by the vision of a new life.’27 This is not a later gloss. Gabo’s association with Gustav Klucis serves to confirm this. A member of the Communist Party and a former member of the crack 9th Latvian Rifles Regiment, who had fought on the side of the revolution, Klucis had impeccable revolutionary credentials, and had exhibited with Gabo and his brother in August 1920.28 It is unlikely that Klucis would have done so, had Gabo expressed anti-Soviet feelings.

Moreover, in his published writings at the time, Gabo also expressed radical affiliations. In the Realistic Manifesto of August 1920, he stressed the relevance of his art to the new social and ideological situation.

On the squares and on the streets we are placing our work convinced that art must not remain a sanctuary for the idle, a consolation for the weary and the justification for the lazy. Art should attend us everywhere that life flows and acts…at the bench at the table, at work, at rest, at play; on working days and holidays … at home and on the road … in order that the flame to live should not extinguish in mankind.29

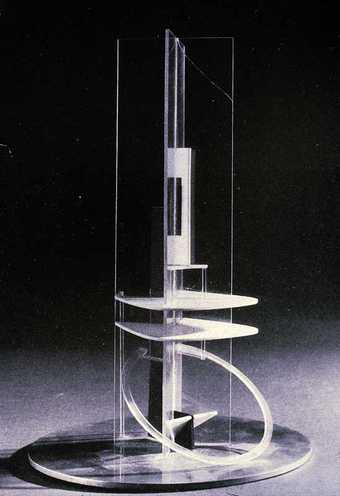

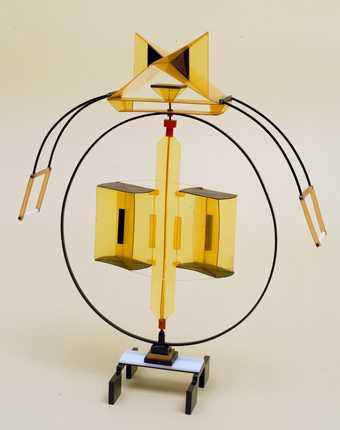

Fig.3

Naum Gabo

Column conceived c.1921, this version before 1928, rebuilt 1938

Celluloid, replaced by Perspex, on metal base

Height 270 mm

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

© Nina Williams

A work like Column (fig.3) seems to correspond to such aspirations and to have been conceived as a public sculpture while Gabo was still in Russia, although the first models were probably executed in Berlin in 1922. Gabo had apparently intended to have the text of the Soviet Constitution engraved on its sides, so that at night lights would play on the work, illuminating the text.30 In this way, the sculpture would have become an effective aesthetic and ideological presence in the city throughout the day and night. Moreover, as a monument to the Soviet Constitution, with a strong political aspect, it clearly relates to Lenin’s Plan of Monumental Propaganda which had been inaugurated in spring 1918.31

The attitudes, therefore, that Gabo seems to have espoused and demonstrated in his work in Russia appear to be broadly in line with a revolutionary political ethos. Of course, his innovative aesthetic ideas did not correspond to the kind of art that the Bolsheviks ultimately wanted to foster within the Soviet Union, any more than the approaches of Kazimir Malevich or Vladimir Tatlin did. Nevertheless, like other avant-garde figures, Gabo was perfectly willing to co-operate with the revolutionary authorities and to create art within official frameworks. This situation changed in 1921, when the government, having emerged victorious in the Civil War, began to take control of the art world and promote a figurative art that could be effectively manipulated for propaganda ends. Accordingly, avant-garde artists were removed from arts administration, notably the Department of Fine Arts (IZO Narkompros), and their influence curbed by restrictions like uniform purchase tariffs. In early 1922 Gabo left Russia, as did many artists eager to see creative developments in the West and to escape the increasing constrictions on experimentation. Many (including Gabo) may have considered the new measures to be temporary aberrations rather than permanent features of Soviet cultural life, and criticism of such measures did not necessarily entail rabid anti-Soviet attitudes.

Indeed, I would suggest that the essentially pro-Soviet, although not uncritical, attitudes that Gabo displayed in Revolutionary Russia continued to determine his activities in the West. Gabo’s diary (in the archive in Berlin) which he began to keep in 1929 indicates that he continued to identify with the political left, rather than with the more reactionary factions of the emigration.32 In January 1929 he wrote: ‘Rebel. Every day, like a prayer, the artist must repeat this word. It is intolerable to live amidst the lies, stupidity and meanness of the capitalist world.’33

Yet Gabo remained a relatively marginal figure during the months following his arrival in Germany in spring 1922 and preceding his public debut in October at The First Russian Art Exhibition. Although his presence coincided with a period of frantic activity in the creation of a ‘Constructivist’ movement in the West, Gabo was on the sidelines.

There is, for instance, no record that he was present at the Düsseldorf Congress in May 1922 or at the International Congress of Constructivists and Dadaists which was held in Weimar the following September and attended by El Lissitzky, Kurt Schwitters, Tristan Tzara, Theo van Doesburg, Hans Richter, László Moholy-Nagy and others. Gabo was not involved with the organisation of the International Faction of Constructivists in May 1922, nor was he mentioned in the magazine Object (Veshch’/Gegenstand/Objet) that Lissitzky and Ehrenburg published in two issues in spring and early summer 1922. Indeed, between spring and October 1922, Gabo’s work was neither exhibited nor reproduced, with the exception of a single image in the Hungarian journal Egység.34 During this time, Gabo seems to have been living with the artist Natan Altman, another organiser of the Russian show, whom he had known in Moscow and with whom he bought artistic materials.35

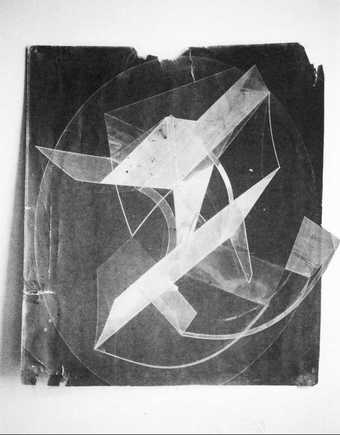

Fig.4

Naum Gabo

Constructed Head No.2 conceived c.1916

Galvanised iron, originally painted with yellow ochre

Height 450 mm

Private collection

© Nina Williams

Gabo may have begun making contacts in the German art world before the opening of the First Russian Art Exhibition on 15 October 1922, but it was the exhibition itself that really launched his career in Germany. Being involved with the show’s organisation was clearly a great advantage. Gabo was able to exhibit nine works (more than most artists) and could thus present a fairly comprehensive view of his development to date. In addition, two of his sculptures were illustrated in the catalogue, Head No.2 and Construction in Space: C, which was generous given the limited number of reproductions (figs.4, 5).36 Equally, Gabo secured a long mention in the catalogue introduction. Indeed, the text about him reads as though he drafted it himself:

Parallel to the Constructivists stands the sculptor Gabo, whose works revolutionise sculpture in such a way that it is no longer ‘sculpture in mass’ but construction. Gabo’s sculptural system is based on the intersected diagonal planes of a basic form which produce spatial construction. Thus space is presented as depth. It is significant that Gabo’s constructions realise not only the static but also the dynamic, and thus also utilise ‘time’ as a new element in art.37

The show was a great success, and Gabo was mentioned in many of the reviews. As a result of its prominence in the exhibition and catalogue, Gabo’s work aroused considerable interest in Berlin. His contribution was discussed in detail by several commentators, and most reviews mentioned him by name.38 Photographs of his sculptures appeared in several articles: Head No.2 was reproduced in the art magazine Das Kunstblatt and in the Communist publication Hammer and Sickle.39 Many of the reviews were enthusiastic. Gabo was described as ‘an original pioneer of a somewhat national stamp’ and as an artist who ‘has successfully tackled the problems of three-dimensional spatial construction in a new way and has developed interesting, if not entirely new solutions.’40 Max Osborn expressed particular excitement: ‘Creative power which would be able to conquer resides perhaps solely in the sculptor Gabo. His glass sculptures are peculiarly visionary.’41 The pro-Soviet Russian émigré newspaper Nakanune called him ‘a talented constructivist in sculpture’ with a ‘great future’ who was creating ‘completely new sculpture’.42 It particularly praised his ‘glass structures’ and Kinetic Construction.43

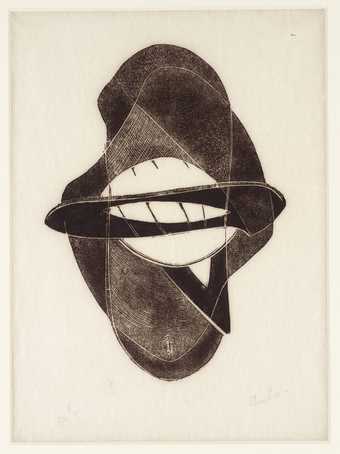

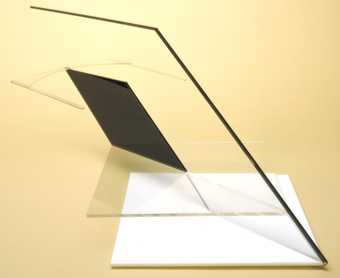

Fig.5

Naum Gabo

Construction en Creux c.1921–2

Plastic and wood

Whereabouts unknown

© Nina Williams

Gabo may not have occupied centre stage in Russia, but his work certainly made an enormous impact in Berlin, so that distinctions between him and artists like Malevich, Tatlin, Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko tended to be obscured. For the Germans, they all seemed equally important. To crown this critical success, Gabo sold Construction in Space C (fig.5), and became acquainted with members of the German avant-garde. He met Hans Richter at the show, who later recalled that ‘Gabo was, for me, the great sensation at the van Diemen Exhibition … I met [him] and we became friends for forty years’:44

I remember well the first impressions of the Unter den Linden exhibition. A huge nude faun in sheet metal stood in the centre of the first room and a similarly constructed head looked down on the nude. These were spatial sculptures, that ‘spaced’ the object from the inside with a bold and sure touch which captivated me instantly. A man of medium height, strongly built, with a flowing mane and flashing brown eyes introduced himself as Naum Gabo, creator of these works. He spoke in a highly expressive style. Even after we had become closely and intimately acquainted with one another, when we took leave of one another, we would go on talking for hours on the landings, with our voices – whether by day or night – increasing steadily in volume, until we were chased away by some resident in need of sleep … [Later] his heavy metal sculptures changed into transparent celluloid panels. In this transparency, the play of space became insightful and many layered.45

Through Richter, Gabo met Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Werner Gräff, and Kurt Schwitters. Many of these figures had previously been active within the Dada movement, but they now formed what Lissitzky described as ‘the nucleus of German Constructivism’.46 Schwitters had been impressed by Gabo’s work at the 1922 exhibition, and became a particular friend.47 Gabo recalled: ‘I met him in the early 1920s in Berlin, when he visited me in Lichterfelde together with Hans Richter.’48 Their subsequent friendship was commemorated by a ‘Gabo Cave’, evidently a phial of his urine, in the Merzbau which Schwitters created in his Hanover house, one of the many homages to his artist friends.49 Later Gabo explained:

We used to take long walks together in the suburbs of Hannover and in the woods. In the midst of the most animated conversation he would stop suddenly, sunk in deep contemplation … One could never guess what had fascinated him in that insignificant piece of ground. Then he would pick up something which would turn out to be an old scrap of paper, of a particular texture, or a stamp or a thrown way ticket. He would carefully and lovingly clean it up and then triumphantly show it to you. Only then would you realise what an exquisite piece of colour was contained in this ragged scrap.50

Gabo was also absorbed into the milieu around Richter’s magazine G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung, which was advertised in de Stijl as ‘the organ of the Constructivists in Europe’.51 Lissitzky suggested the title and been involved in editing the first issue. 52 ‘G’ was evidently short for ‘Gestaltung’ which encompasses both the process of organising forms, or form-making, and the results of that process in design, architecture and art. The journal’s ideological stance was expressed in the first issue of July 1923 by a quotation from Marx placed vertically like a banner on page three: ‘Art must not explain the world, but change it’.53 Gabo supplied ‘Theses from the Realistic Manifesto, Moscow 1920’,54 which compressed the manifesto’s argument into four essential points: the importance of life as the starting point for art, the emphasis on space and time, the rejection of mass and the espousal of kinetic rhythms as a means of expressing time.55 These reflected the essence of the 1920 document and continued to govern Gabo’s various activities. He did not contribute to subsequent issues of G, which concentrated increasingly on architecture and design. Nevertheless, his participation in the first issue publicly allied him with the radical Constructivist ethos which was emerging in the West. Unlike its Russian counterpart, this combined a commitment to art, as a symbolic representation of the potential new order, with an engagement in the more practical task of reconstructing the visual environment.

Yet despite Gabo’s extensive contacts with avant-garde figures in Germany, he never became a central figure within the indigenous avant-garde. In this respect, he does not seem to have built effectively on the success generated by the exhibition. One reason may have been his health. In spring 1923 he caught pneumonia and spent two weeks in hospital. He then recuperated with Lisa Richter. So in the crucial aftermath of the exhibition, Gabo was effectively out of circulation. Once he was better, he did try to generate outside interest in his work. In summer 1923, he visited the Bauhaus with Lissitzky, but this did not result in any commissions for lecturing or teaching for either of them. Evidently, there were few openings at the school as Moholy-Nagy represented international Constructivism. Gabo did not fare much better in securing shows for his work. He only exhibited twice in Germany between 1922 and his one-man show in Hannover in 1930. In 1926 he contributed two works to the Novembergruppe section at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition.56 That June, Rotating Fountain (fig.6) was included in the remarkable installation of Constructive Art which Lissitzky designed for the International Art Exhibition in Dresden.57

Naum Gabo

Model for ‘Rotating Fountain’

(1925, reassembled 1986)

Tate

The Work of Naum Gabo © Nina & Graham Williams / Tate, London 2023

Gabo was not impressively productive as a sculptor while he was living in Germany. The dating of the works in the catalogue of his one-man show in Hannover indicates that in the eight years between the 1922 exhibition and the opening of this show he had produced at least thirteen new constructions.58 There may have been more. Some of these seemed to relate quite closely to the creative concerns that had inspired his work in Russia; others were more relevant to capitalist Germany. Gabo, for instance, started developing projects for fountains, and a type of public sculpture that would be suitable for the capitalist environment like Monument for an Airport (fig.7). One of the designs for fountains, Rotating Fountain, was actually constructed (fig.6).

Naum Gabo

Monument for an Airport

(c.1932–48)

Tate

The Work of Naum Gabo © Nina & Graham Williams / Tate, London 2023

In part, Gabo’s limited output as a sculptor was related to the fact that he became very involved with architecture and design. His connection with architects seems to have dated from the First Russian Art Exhibition. He recalled:

Peter Behrens came up to me in the [1922] exhibition and said ‘The whole exhibition is nothing, but your works mean something to me, they are extraordinary. Could you give a lecture in the Architects’ Club?’ I said all right and gave the lecture. From then on I was with architects all the time. Poelzig was excited by my work.59

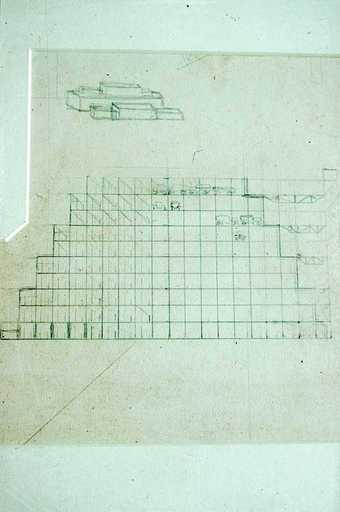

Fig.8

Naum Gabo

Design for a Multi-storey Car Park 1925

Watercolour, ink and pencil on paper 226 x 402 mm

Berlinische Galerie, Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Photographie und Architektur, Berlin

© Nina Williams

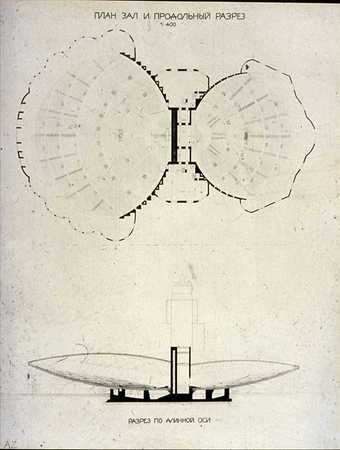

Subsequently, Gabo became involved with several different areas of design. He devised a light show for Berlin; he created a three-dimensional typeface that was clearly conceived to be used in advertising and he produced various architectural projects which involved new building types such as airports and car parks (figs.8, 9). Towards the end of the 1920s, he even gave some lectures at the Bauhaus and wrote about design for the school’s journal.60 This aspect of Gabo’s activity culminated in 1931, when he submitted a project for the Palace of Soviets Project (fig.10). Fortunately, he kept photographs of his design, which remained in his archive. In Russia, his design sunk without trace.

Fig.9

Naum Gabo

Submitted Design for Palace of Soviets: Plan of Main Hall and Section (sheet 3) 1931

Pencil and india ink on paper 983 x 855 mm

Whereabouts unknown

© Nina Williams

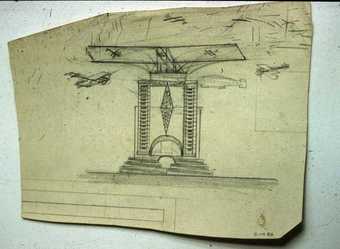

Fig.10

Naum Gabo

Sketch for a Tower with an Aircraft Carrier Platform c.1924

Pencil and ink on paper 190 x 263 mm

Berlinische Galerie, Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Photographie und Architektur, Berlin

© Nina Williams

Gabo seems to have enjoyed some success in establishing an international reputation and contacts. After The First Russian Art Exhibition was shown in Amsterdam, Gabo was invited to Holland to lecture. Ernst Kállai (Ernö Kállai) wrote about him in the Dutch avant-garde journal i.10.61 In 1924 Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner had an exhibition at the Galerie Percier in Paris, where they were announced as ‘Constructivistes Russes’, and Gabo sold several works including Construction en Creux and a Head No.2.62 The brothers built on this success by contributing a couple of works, two years running, to the spring Salon des Indépendants in Paris.63 In 1924 Gabo showed two works in Vienna.64 The brothers also exhibited and sold some works to America.65 In 1927 they produced the decor and costumes for the Ballet La Chatte for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which premiered in Monte Carlo, but travelled to Paris, London and elsewhere in Europe.

By the early 1930s Gabo had established his reputation in Germany and elsewhere. Yet in comparison with a figure like Lissitzky, Gabo was far less prominent and successful. Lissitzky (before he returned to Russia in 1925) occupied a central position within the German and international avant-garde. He had attended the Düsseldorf and Weimar congresses; had helped to set up the International Faction of Constructivists; had published the journal Object (Veshch’/Gegenstand/Objet) with two issues in 1922; had organised several solo exhibitions; had sold many works; had published A Story of Two Squares and Sieg über die Sonne (1923); had written for De Stijl; had designed Vladimir Maiakovsky’s For the Voice (Dlia golosa, 1923); had prepared an issue of Schwitter’s Merz journal; had lectured at the Bauhaus; and produced numerous advertisements for commercial organisations like Pelikan ink.66

The explanation for the difference in the success that Gabo and Lissitzky enjoyed is not linguistic. Both artists spoke German well. Both had received university educations in Germany prior to the First World War: Lissitzky in Darmstadt and Gabo in Munich. Both had a good grasp of German culture. Neither had established relations with German artistic circles when they were students, so in Berlin both artists had to start from scratch building relationships with German creative circles. Both arrived at the right moment, when interest in Russian developments was at its height and a broadly Constructivist ethos was emerging. Gabo occupied centre stage in Berlin from October 1922 until spring 1923, but he does not seem to have capitalised on this. He may have lost momentum because of illness. It could also be argued that he dissipated his energies in various directions, including developing international links and becoming involved in design. Most importantly, he was a sculptor; sculpture was a difficult medium for the art market – materially intensive, expensive to make, not very portable and not immediately accessible to an audience.

Yet Gabo’s achievements while he was in Germany, especially in the latter years, were not inconsiderable, and it is possible that he might have succeeded in carving out a firmer and a more central niche for himself if Hitler and the Third Reich had not intervened. As it was, in 1933–4 Gabo left Germany in stages, taking with him a large archive, which now comprised actual works, models, sketches of ideas for sculptures, various architectural drawings and designs, including copies of his Plans for the Palace of Soviets, copies of the Realistic Manifesto, catalogues of his individual and group exhibitions, his published writings in German; his unpublished writings in Russian and German, including the texts of his various lectures such the text of his Hannover talk in 1930; diaries and notebooks that he had written in Germany; photographs of a personal nature; letters from family and friends; and money.

This was now the archive of an artist who was taking his whole life with him. He had perhaps become more resigned to being an émigré. He had not given up the hope of returning to Russia, but by 1933, it was far more likely that he would stay in the West than that he would return to the Soviet Union. As Stalinism became entrenched, even contact with his family was broken and the prospect of return became remote. In 1936 a letter to his brother Alexei Pevsner, still in Moscow, was returned with the inscription ‘refused to be accepted’.67 It was only in 1959 that the brothers found each other again.68 For over twenty years Gabo had no idea how his Russian family was living.

In contrast to his experience in Germany, Gabo was much more successful in Britain. Once again he arrived at the right time as a British Constructivist movement was emerging, and his career was launched through an exhibition.69 Now, however, he had established contact with the main protagonists before moving to London, and he immediately became involved in publishing Circle and thus in a promotion venture that would make his ideas widely accessible, but perhaps most crucial were the facts that Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore had already made sculpture more central to avant-garde activities in Britain than the medium was in Germany, and Gabo was now the sole representative of the revolutionary Russian avant-garde in London.70