The lives of Net Art, an Introduction by Kit Webb (2021)

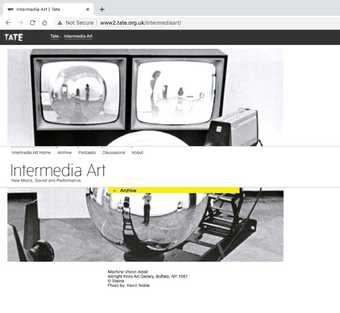

In the year 2000, amid the fuss and tumult that accompanied the opening of Tate Modern, a small initiative was launched, with somewhat less ceremony: another new space for art. Tate Online, as it was then known, became home to the institution’s first forays into the field of net art – art made for and using the internet. Over the following eleven years, fifteen works of net art were commissioned by curators working within Tate’s National Programmes and Digital teams (and the latter’s precursors). Initiated at a time when a number of institutions were commissioning net art – including Iniva, Walker Art Center, Whitney Museum of American Art and Dia Art Foundation – Tate’s programme was intended to reach audiences beyond London, and to respond to state-endorsed directives to make art more accessible. As the works were commissioned, not bought, they did not become part of Tate’s collection, but were licensed for display on Tate’s website. Today, the pages that came to host these artworks – titled ‘Intermedia Art: New Media, Sound, and Performance’ – remain accessible from Tate’s servers (though isolated from Tate’s website).

The research we have undertaken has sought to explore the ‘lives’ of these commissions: how they came to be produced, the contexts and networks within which the commissioned artists were working, and the way they can be said to ‘live on’ today. Understanding artists’ attitudes towards the conservation and legacy of net art has been central to our work. Have they sought to preserve or adapt their artworks? Do they consider them as projects, which might be active for an allotted period of time, but need not culminate in the distinct, discrete objects that museums more often traffic in?

From our position working within Tate, we have sought to explore the museum’s role, past and present, in supporting and commissioning net artists and preserving their artworks. This history – of these artists, their artworks and their interactions with organisations – continues to be at risk of loss, as technologies become defunct, web domains expire and other records are lost in website upgrades and server migrations. In reassessing this institution’s belated, tentative engagement with net art, we have been prompted to ask what parts might be played by curators, conservators, registrars and archivists in the preservation of this history. How might the relationship between museum, artist and artwork function differently in the future? The texts in this collection document the work we have undertaken to preserve, to archive and to reconstitute and elaborate the record of what took place. They seek to contextualise and to celebrate the commissioned artworks and the artists who made them. They gesture forwards too, to the future lives of these artworks and to the ways in which a collection might be reshaped under their influence. Finally, they register doubts about these futures, both those of the artists who have generously given us their time and their thoughts, and our own.

In the first of the texts, ‘“Dusty Navigational Pathways”: Net Art in the Museum’, Lucy Bayley delves into the history of the fifteen commissioned net artworks. Through an analysis of the anti-institutional leanings of early net artists, and their search for alternatives to large cultural infrastructures, Bayley reflects on what it means to now examine these practices from within a museum, and with tools drawn from art history. Her writing addresses ‘net art’s fluctuating visibility and invisibility both inside and outside of the institution’, and the challenges that surround the collection and historicisation of these works. In a paper published separately in Stedelijk Studies, ‘Seep Between the Mortar: Sociotechnical Imaginaries in Digital Media at Tate’, Bayley considers Tate’s digital media strategies between the mid-1990s and 2013, and considers what persisted and what failed.

Together with Time-based Media Conservators Patricia Falcão and Christopher King, Bayley has also co-written texts (forthcoming) profiling the fifteen commissions, drawing on interviews conducted with each of the artists. These texts describe the artworks and how they were experienced, situating them within the artists’ practices and tracing their reception through the work of critics, curators, artists and academics. Falcão and King have also contributed technical descriptions, documenting the technologies employed by the artists and their current condition.

Essential for our continued access to many of these commissions, as well as a rich trove of information about them, is the Intermedia Art microsite. Sarah Haylett’s research takes the microsite as a crucial archival record, and one at risk of further loss as web technologies fall out of use (and Tate’s web servers migrate). In ‘Contextualising the Intermedia Art Microsite 2008–12’, Haylett narrates the story of how the microsite came to be and describes how it functions today, framing this within the wider evolution of Tate Online. In her second text, ‘Websites as Records: Archiving the Intermedia Art Microsite’, Haylett provides an overview of web archiving, detailing the process and tools that she, alongside Falcão and King, used to archive the Intermedia Art webpages.

Our research has resulted in proposals for changes to museum practices. Stephen Huyton, in his ‘Creating Collection Management System Locations for Digital Artwork Components’, discusses how Tate’s collection management system has been adapted to better document the display of digital artworks, as well as the movement and storage of their components. His second essay, ‘Reflections on Commissioning and Licensing’, details the mechanisms by which these examples of net art were produced and displayed on Tate’s website. In doing so, he is prompted to reflect on why commissioning and licensing might be considered useful alternatives (and not just for digital artworks) to Tate’s preference for holding title to works in its collection.

In a similarly speculative mode, independent curator and former Brooks Fellow Marina Valle Noronha uses ‘(Net) FOREVER Art :)’, her report on the Lives of Net Art events held in April 2019, to consider what artists, curators and conservators might be able to learn from an embrace of net art’s impermanence.

These texts mark a waypoint on Tate’s own journey in developing the capacity to display and care for net art. As much as they are a culmination of our research, they also form beginnings for work that continues within the institution. We hope that these texts allow you to discover, or discover again, these artworks and the artists who made them. They serve both as a reminder of what we are at risk of losing and as a proposal for how we might save and build upon this moment of programming. Finally, we hope that they project the outline of an art museum reshaped by the challenges and opportunities posed when net art is brought in from its edges.

Net Art: a case study for change in the museum, by Sarah Cook (2023)

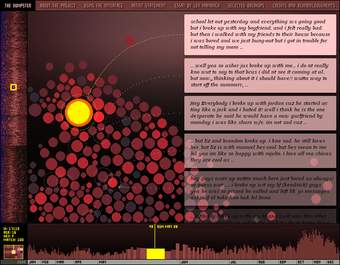

The research project Reshaping the Collectible, of which this case study into net art is a part, has sought to determine how works of art ‘live’ in the museum, and how the museum might change in response to ‘living’ with these artworks. The anthropocentric framing of artworks as having lives, with stages of birth, maturity, and in some cases death, belies an important conceit: that artists might choose to create work other than with or for the museum. This is particularly important for the fifteen net artworks commissioned by Tate between 2000 and 2011, which sit in an ethereal position, neither fully in, nor fully out of the Tate’s conceptual if not physical environment. Today, the pages that came to host these artworks – titled Intermedia Art: New Media, Sound, and Performance – remain accessible from Tate’s servers (though isolated from Tate’s website). For the most part, the artworks themselves do not, though each work has a different complex story as to why it currently is or isn’t online, as we discovered.

A number of stages of research were evidenced in this project, both those public and well-documented (undertaken with audiences) and those that are less visible (undertaken with the artists and on and through the web). These include interviews, discursive events, reading, writing, and software preservation experimentation.

A primary aim of this case study was to ask how both artists and the institution think about the legacy of these works. At the time of writing the field of net art is undergoing repeated, overlapping (and weirdly geographically separated) processes of art-historical canonisation. Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology has set the bar in making works of net art accessible through diverse means of emulation, recontexualisation and documentation. In 2018 LIMA (the media art organisation in Amsterdam which grew from NIMK, the Netherlands Media Art Institute, and before that MonteVideo) announced the restoration of twenty works of born-digital art in the Digital Canon (1960–2000) of the Netherlands. The research project The Net Art Coordination Centre began in the same year, joining such artist-led initiatives as the zentrum für netzkunst in Berlin.

Preserving the net art works commissioned by Tate and adding them to the museum’s collection was not an explicit aim of this case study, nor of the wider research project. The research we have undertaken has confirmed Kit Webb’s warning in the earlier introduction that ‘the history itself – of ‘these artists, their artworks and use of technologies, and their interactions with organisations’ – continues to be at risk of loss’. With net art, as with other site-specific or time-based ‘electronic’ art, it is not only the artwork at risk of loss, but the entire (programming) context that the artwork was ‘born’ into. This context includes the infrastructure that we call ‘the internet’ between 2000 and 2012, and the museum itself.

As such, one major outcome of this research is a series of extended texts about each of the commissions and their contexts. These are neither straight art-historical object biographies, nor what the Tate calls ‘summary texts’, which are short texts that are, in part, published on the artwork pages of Tate’s website, mostly written by curators during the acquisition process. The net art commission texts are more expansive, providing social and artistic context as well as in-depth technical narratives. Together they help to fill a gap in the knowledge around web-based art, establishing the groundwork for sustainable preservation, and with it, the possibility of accession.1

The texts are written in collaboration with time-based media conservators Patricia Falcão and Christopher King, and the art historian Lucy Bayley, to which I contributed conclusions that reflect on the art-historical context of each. Describing the media archaeological and experimental preservation approaches they took and addressing the technologies employed by the artists, the authors sought to determine whether reconstruction or representation of the works was possible, or even desirable.

Given each net artwork’s differing condition of accessibility, Patricia Falcão’s essay ‘Another Case of Uncomfortable Proximity? Keeping Web-based Art Online at Tate’ considers the overall conservation and preservation of the artworks at the centre of the study. Emerging from the museum’s ‘recognition of the cultural importance of web-based art and the lack of institutional expertise and infrastructure to support’ net art, the case study enabled Falcão to identify the steps needed to secure the future of the commissions. The ‘uncomfortable proximity’ of this approach (a term Falcão takes from Graham Harwood’s commission for Tate) comes from the fact that conservators are unable to carry out such future proofing for works of art which are not in, or anticipated to be coming in to the collection. Committing to accessioning these works, Falcão argues, would empower the museum so that ‘resources can be made available for full preservation interventions, and so that the infrastructure and knowledge that already exists in the institution can be widened to support this part of art history’.2

Taken together, these texts are a major milestone in the work we have undertaken to preserve, archive, reconstitute and elaborate the records of web-based art. The Lives of Net Art event in April 2019 was a crucial moment to reflect and audit the organisation and identify routes forward. For many of the artists it was the first time they’d been asked to Tate to talk about their commissioned work. The keynote lecture by Christiane Paul, curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art and co-commissioner for three of the net art works, is available in video form, and has been widely viewed since its publication online.3

The Lives of Net Art event was also a moment to capture some of these artists on record. In an extended period of production, interrupted by the pandemic and staff changes, a short video was released in May 2022 titled ‘What are internet art works and how do we care for them?’. Featuring some of most active contributors to the net art scene in the early 2000s, such as Gary Stewart at Iniva and Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow at Furtherfield, the film ends with a discussion by Falcão about the work’s preservation. Viewed over 11,000 times at the time of writing, the video communicated the urgent and important need for digital preservation to an audience beyond the topic’s usual circles.

In 2022, as museums and galleries reopened after successive pandemic lockdowns, a display titled ‘The Lives of Artworks’ was installed in the learning gallery at Tate Britain. It was the subject of audience research informing the communication of the work-in-progress of the Reshaping the Collectible project. The display linked together the case studies in the research project, screening the net art video as well as short videos created for other technologically-created artworks subject to conservation, documentation and potential representation (such as Tony Conrad’s Live on the Infinite Plain), as well as provided links to an audioguide for works on display in the nearby galleries, which included the CD-Rom Autoicon by Donald Rodney and the video installation Belshazzar’s Feast by Susan Hiller.4

Other bits and pieces of research linked to the net art case study remain less visible, but may result in greater sector changes. This includes advocacy for these works, and the artists who made them, undertaken by Pip Laurenson and Sarah Cook, beyond the important presentations at curatorial meetings at Tate. Continually remembering and highlighting the history of net art has become critical for engaging in many distributed discussions and debates across the sector, such as in those about the newer digital initiatives artists and museums are engaging with, namely NFTs and generative art. The net art research was also presented and discussed in educational contexts (enhancing the curriculum on museum studies programmes, such as the one I teach on at the University of Glasgow, and with work placement students such as those from New York University’s Time-based Media Conservation programme), and at conferences on topics as diverse as digital humanities or collections management.5 Most importantly, this advocacy work, and the critical preservation work undertaken by Patricia Falcão and Chris King, triggered further internal discussions at Tate, and a commitment to define and agree the infrastructure needed to support web-based works, in a collaboration between staff from the departments of Time-based media art conservation, Technology and Digital.

In the original introduction to this case study the words ‘tentative’ and ‘belated’ were used to describe Tate’s relationship to net art, both at time of commissioning and at the beginning of the research project in 2018. The resulting research sought to interrogate the relationship between museum, artist and artwork both retrospectively and going forward. Some of the resulting research has been deliberately tentative in its attempts to contextualise the commissioned artworks and the artists who made them, recognising that creating an art historical canon after the fact would be a false and fraught exercise. Instead, this case study reaches back in order to stretch forwards, to the future lives of artworks like these, and to the ways in which a collection, and museum practices, might be reshaped under their influence. Finally, much of the research produced registers doubts about these futures. Through it all, however, the spirit we began with – a commitment to using the web as a space to extend creativity, and to do it with others – remains.