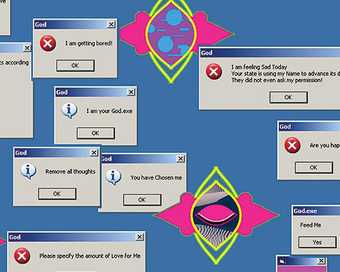

Fig.1

Broken links. The domain name which once hosted Shilpa Gupta’s Blessed Bandwidth 2003 now shows a ‘temporary Parking Page’, http://www.blessed-bandwidth.net, accessed 1 August 2019.

With its dependence on the fast-moving flow of new technology, net art works can suffer the effects of obscelence surprisingly quickly. They can feel as impermanent as a regularly updated webpage, what’s visible when scrolling through social media, or the changing waters of a river. Seemingly minor changes or updates in software might mean that works stop functioning as intended after just a year, or even months. Over time, it might be impossible to see the work in its initial state, or any part of it. In other words, their initial state is short-lived. To live FOREVER in net art is usually impossible.1 The drastic transformation from an artwork which is accessible from almost everywhere to an entirely inaccessible one is manifest in net art’s broken links (fig.1). How can artworks that are bound to change be collected?

The chance to participate in the Lives of Net Art events during a week-long visit to London expanded my thoughts about the importance of museums re-thinking current notions of collecting in order to be able to respond to the needs of the artworks they collect. Among other talks and presentations, Dragan Espenschied, Preservation Director at Rhizome, offered an insight into current approaches to preserving net art and the temporalities of an online archive; curators Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Sarah Cook brought inspiring thoughts on what gets registered when collecting and curating net art, as well as what can be learnt from reading the way works are stored and archived; and mentions of Annet Dekker’s work echoed different perspectives into curating, archiving and collecting. I began to realise that similar things that happen to net art also happen to other objects in collections.

For me, the events highlighted the need to find better ways to engage with artworks at large, especially the ones that do not conform to conventional notions of collecting. In this short article, I look at Tate’s net art commissions and the challenges involved in preserving and collecting net art from a curatorial perspective. I refer back to the initial mission statement of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York as a way to find a refreshing approach to tackle this issue. The questions we have about collecting net art might also help with other challenges, and with re-thinking ideas of how museums collect.

If we scroll down the page – backwards in time *really* fast – we find ourselves at MoMA in 1931, when the museum collection was described as having the permanence of a river.2 Works acquired by the museum would stay in the institution for no longer than thirty years, after which they would flow out of the museum to other institutions. This was MoMA’s way of assuring contemporaneity would always be present in the art collected by the museum – the permanent collection was replaced by the continuous presence of impermanence.

The experiment was (unfortunately) short-lived. What once felt radical was cut short in the early 1950s when MoMA took a step back towards the norm.3 Since then, artworks at MoMA, as in most museums, are understood to form part of a ‘permanent’ collection. We were perhaps not ready then and I suspect we are not ready now to fully accept such a radical move. We tend to believe that artworks (and the idea of art) should be preserved in a collection in perpetuity. It’s sometimes hard to imagine that an artwork might actually not live FOREVER or exist indefinitely in the collection that holds it. This tendency prevents us from seeing artworks – and the process of collecting them – in perspective, and so also from imagining different possibilities for them.

Fig.2

The page for the Infrequency Podcasts series from 2008, http://www2.tate.org.uk/intermediaart/podcasts/infrequency.xml, accessed 1 August 2019. The page has lost all design and formatting information, making it almost impossible to navigate.

Fig.3

The page for Qubo Gas’s Watercouleur Park 2007, http://www2.tate.org.uk/netart/watercouleurpark/flash.htm, accessed 1 August 2019 using Google Chrome web browser. At the time this screenshot was taken, the work still ran on an old version of Flash Player (though browsers did not automatically enable the plugins required to view net art works). Since Flash was discontinued on December 31, 2020, the work is now completely inaccessible.

Emerging in the 1990s, net art employs and is made for the internet and its users. It counts on the fast pace, unlimited possibility and freedom that the platform can offer. The impermanence that MoMA initially proposed for its collection is a common characteristic of net art. Achim Wollscheid’s Nonrepetetive 2011 was closed after only a year;4 the Infrequency Podcasts series, hosted on the same Intermedia Art webpages as the net art commissions, directs to a page now displaying the error message ‘[that] XML file does not appear to have any style information associated with it’ (fig.2).5 You might try to figure how the ‘document tree’, the lines of text coding that appear below the message, relates to the work, and when it crashes, ‘You can wait for it to become responsive or exit the page’. For other works ‘You need[ed] to upgrade your Flash Player’ (fig.3) but the browser you use no longer supports the outdated plugin the artwork ran on.6 Annet Dekker sums up the speedy obsolescence of net art works: ‘it’s important to acknowledge that [net art] is never stable – since technological changes and updates continuously shape the work – and to see them as localised and specialised entities in time, both in the sense that they can be time-based and that their appearance may vary over time.’7 Without institutional support, artists are also expected to maintain their artworks themselves, taking on the cost of paying for domain names and security updates. This can of course be prohibitive, further contributing to the work’s impermanence. When they are hosted by institutions like Tate, updates to the larger website can render them either non-functional or difficult to find.

One can argue that tools like the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, that provides access to archived web content for future reference, can in some cases, and to a limited degree of functionality, provide access to net art that has become inaccessible over time.8 Archives of the internet do not fulfil the role of a museum that can collect and show works to those who want to see them. Rather, they usually ’harvest’ or ’scrape’ the works incompletely or at odds with how they were originally experienced. So how do you collect works that are based on change? Espenschied refers to artworks as ‘blurry objects’.9 According to him, the object is ‘blurry’ because in order to preserve it, you need not only the object itself (the code, in the case of net art), but also the environments on which it is dependent (the computing and network infrastructures which allow net art to function) – the artwork doesn’t exist in one clearly defined form, and its boundaries are ‘blurred’ by its external dependencies.

During the Lives of Net Art event, the curator Christiane Paul presented on Project Xanadu, proposed by Ted Nelson in 1960. Claimed to be the explicit inspiration for the internet, the project was a machine-language program which would store and display documents, together with the ability to edit them.10 The very ability to perform edits – decompose, subtract, add, derive, generate, explore – that is used so much by net art might be missing from the way museums collect these works. We might ask: How far can one go in making changes to objects? What if their broken links are ‘restored’ not necessarily to their ‘authentic’ state, but to a state that, like Dekker says, ‘moves away from the purely material to include the original experience and contextual meaning of the artwork’?11

To look at things from a different perspective, we can zoom in on an example from the Guggenheim, New York. Brandon 1998–9 is an extensive net art work by Shu Lea Cheang. Centred around the tragic rape and murder of Brandon Teena, a young transgender man, in 1993, the work raises issues of gender and identity.12 When presenting the conservation strategy for Brandon, conservator Joanna Phillips noted the relevance of understanding the behaviour of an artwork – how it’s supposed to work and the reasons why it no longer operates as it should. Parts of Brandon were no longer accessible or displayed properly because of numerous broken links. In a joint initiative between the museum and New York University, the restoration team at the Guggenheim, New York, chose to prioritise informing the viewer that some parts of the artwork were broken, and a new restoration method was developed for the work. This approach brings the conservation right into the core of the artwork – it acknowledges and accepts its broken links. Instead of overwriting the artwork’s old code with an entirely updated one, they developed a code that could coexist with the initial one, focused specifically on the parts of the artwork that were lost due to changes in technology.

Brandon is not only a significant early net art work for the Guggenheim collection but also a response to a shocking and tragic event. It is of course best to be as transparent as possible when dealing with its conservation. By adding a new layer of code the work’s continued relevance is recognised and the museum evolves its collecting and engagement with the piece. Brandon’s restoration is a good example of artwork, conservation, museum and artist learning from, and adapting to, each other. User data, colour interpretation, speed, focus, word truncation, original code, choice of technology and programming languages are all present in the work. Is there a chance, though, that it might still be important to hold on to the original materials of the artwork despite their broken links or missing parts? Zoom out.

I add to Dekker’s words that it is not necessarily the way an artwork looks, or ‘the purely material’ qualities, that are its most valuable features, but the properties it holds, accumulated throughout its time in a collection. By following the artwork as it flows down the stream of the collection, a museum provides visitors with a truer, more honest engagement with the works. In turn, the objects’ changes over time are acknowledged by the museum. This might be the closest we can get to providing the fullest possible history of an artwork.

We need to accept that artworks are time-based entities – they change over time – and that what characterises them is change. Dealing with their broken links and missing, changing or crumbling parts is a way to get away from the traditional idea that artworks should hold on to an ‘original’ state. Acknowledging the cross-temporality of artworks could be a way to come to terms with the impermanence that things hold, even as we hope for them to ‘survive FOREVER’. We need to explore how the changes net art works undergo through time contribute to their character, can feed into strategies for their preservation, and prevent them from simply being lost at the next scheduled update to the website.