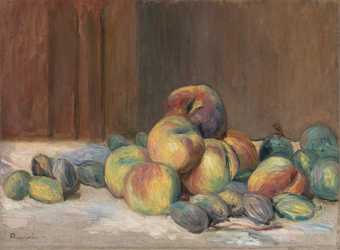

Auguste Renoir

Peaches and Almonds

(1901)

Tate

Renoir was one of the five sons of a poor tailor and himself went through years of poverty, too hard up at times even to buy paints.

His first great successes came in the 1870 and 1880 when he was taken up by a few wealthy and cultured patrons like the Bérards and the publisher Charpentier, who commissioned him to do portraits of their wives and children.

In the paintings made for such patrons there is extraordinary charm, but also a certain effort at refinement, a prettiness amounting almost to chic, which suggests that Renoir was in danger of becoming a fashionable portrait painter in the sense of making concessions.

But, for better or worse, this did not happen. As Renoir said later, he disliked painting society beauties because ‘their skins did not take the light’ and their hands, too elegant and white, lack the character which house-work gives.

Most of the pictures of his last thirty years were painted from his maids (Gabrielle especially), whose black hair and ruddy glowing cheeks may be recognised again and again. His children also served as models, in particular the young Coco (Claude).

‘Around 1883,’ he later confessed, ‘a sort of break occurred in my work. I had gone to the end of Impressionism and I was coming to the conclusion that I did not know how either to paint or to draw. In a word, I was at a dead end.’ He destroyed a number of canvases and set about acquiring the craftsmanship he supposed he lacked, in particular concentrating on drawing.

By the early 1890 his painting had become looser again, and in the following years a strong tendency towards extreme plasticity and hot colour became evident. Though crippled by arthritis, he painted with a brush attached to his wrist.

The great achievement of Renoir’s last years is surely his sculpture. In some of his late paintings from 1900 onwards, the plasticity is so strongly marked that figures seem to protrude from the canvas in a kind of polychrome high relief.

John Rothenstein