What can images and objects tell us about how colonialism shapes our understanding of the past and the present?

Colonialism is a violent system of control achieved through the exploitation and extraction of labour and resources. Growing up in the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a region rich in natural resources, Baloji’s work explores the drain on human and natural resources that shape ongoing colonial legacies. As Baloji has stated, ‘I am not interested in colonialism as nostalgia, or in it as a thing of the past, but in the continuation of that system.’

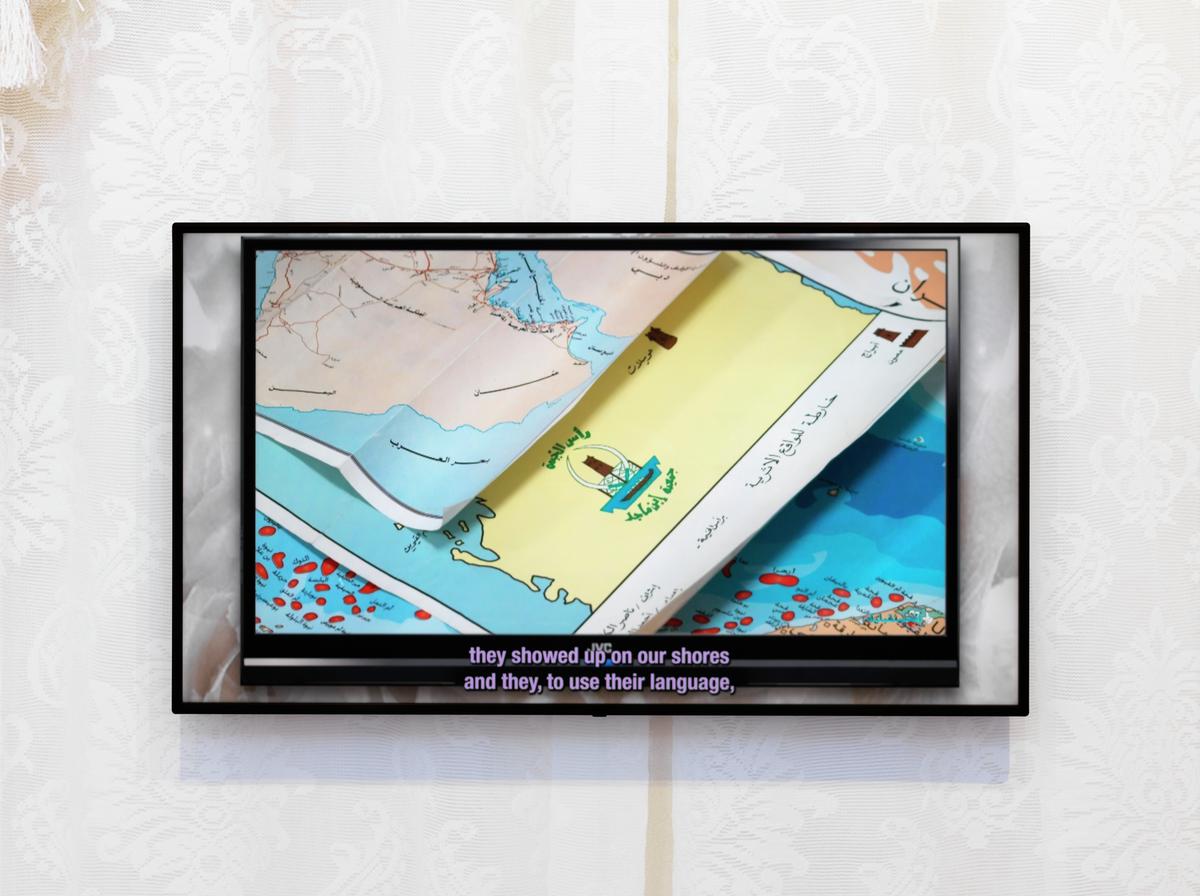

The installation is centred around the mining and circulation of copper, a mineral that is central to the country’s economy and political conflicts. Nearly all copper from DRC was extracted and exported for large-scale industrial use, impacting local infrastructure and livelihoods. Arranged to look like classified museum objects on a plinth, the mortar shells are displayed here as planters. Baloji has filled them with plants indigenous to central Africa’s copper belt, now commonplace in botanical gardens across Europe. The title of the work refers to phrases from the Vocabulary of Elisabethville (1965) by André Yav, a book documenting the contribution of African soldiers and communities to the First and Second World Wars.

The work also includes archival photographs found in a Belgium ethnographic museum. Taken during the colonial era, the images document the scarification of the body – a practice commonly used across Africa during initiation rites as a means of identifying a person’s community. These photographs show the common colonial practice of othering African subjects through scientific and ethnographic studies. Commenting on the connection between scarified skin and mined copper, Baloji hammered each photograph by hand and inscribed the copper plates and wallpapers with scarification patterns.

Baloji reclaims the material and embodied histories of his home country in order to change the ways in which we see the past and the present. He says, ‘It was interesting for me to find these traces of the pre-colonial system. There was a whole cultural, social, aesthetic and meaningful system in place before, and working with copper was a way to re-direct the system, denouncing the political and economic impact that colonialism had in the Congo.’

Art in this room