Sir John Everett Millais, Bt

Ophelia

(1851–2)

Tate

Introduction

Ophelia is one of the most popular Pre-Raphaelite works in the Tate collection. The painting was part of the original Henry Tate Gift in 1894. Millais’s image of the tragic death of Ophelia, as she falls into the stream and drowns, is one of the best-known illustrations from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet.

The Pre-Raphaelites focused on serious and significant subjects and were best known for painting subjects from modern life and literature often using historical costumes. They painted directly from nature itself, as truthfully as possible and with incredible attention to detail.

How was it made?

Part of the Hogsmill river where Millais is thought to have painted Ophelia

Millais painted Ophelia between 1851 and 1852 in two separate locations. He painted the landscape part of the painting outside, by the Hogsmill River at Ewell in Surrey; and painted the figure of Ophelia inside in his Gower Street studio in London.

At the time Millais was painting, it was common for artists to work outside to produce sketches. They then took these back to their studio and used them as reference to create a larger finished painting. However, Millais and his Pre-Raphaelite friends completed their paintings outside in the open air, which was unusual for the time.

Millais did not give himself as long to paint the figure of Ophelia as he did to paint the landscape. Traditionally, the landscape was often considered the less important part of painting and therefore painted second. Millais and the Pre-Raphaelites believed the landscape was of equal importance to the figure, and so for Ophelia, it was painted first.

Posing for Ophelia

Millais’s model was a young woman aged nineteen called Elizabeth Siddall. She was discovered by his friend, Walter Deverell, working in a hat shop. She later married one of Millais’s friends, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in 1860.

To create the effect of Elizabeth pretending to be Ophelia drowning in the river, she posed for Millais in a bath full of water. To keep the water warm some oil lamps were placed underneath. On one occasion, the lamps went out and Millais was so engrossed by his painting that he didn’t even notice!

During her time posing for the painting, Elizabeth got very cold and became quite ill. With no National Health Service or readily available medicine, Elizabeth was looked after by a private doctor paid for by Elizabeth’s father who then ordered Millais to pay the fifty medical bills. The matter was settled and Miss Siddall recovered quickly.

While posing, Elizabeth wore a very fine silver embroidered dress bought by Millais from a second-hand shop for four pounds.

Detail of Ophelia's dress

Tate, London (2003)

To-day I have purchased a really splendid lady’s ancient dress- all flowered over in silver embroidery-and I am going to paint it for ‘Ophelia’...it cost me, old and dirty as it is, four pounds.

John Everett Millais

PREPARATORY SKETCHES

For such an important painting, Millais only made a few preparatory sketches for Ophelia. An oil study Head of Ophelia (with Wreath) was produced in 1852, but its current whereabouts are unknown.

Sir John Everett Millais

Study for the head of Elizabeth Siddal 1852

© Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

Sir John Everett Millais

Study for Ophelia 1852

© Plymouth City Council (Arts and Heritage)

Sir John Everett Millais

Slight Sketch for the painting Ophelia 1852

© The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, 1973. 15 verso

The Inspiration

Ophelia is a character in Hamlet, by William Shakespeare. She is driven mad when her father, Polonius, is murdered by her lover, Hamlet. She dies while still very young, suffering from grief and madness. The events shown in Millais’s Ophelia are not actually seen on stage. Instead they are referred to in a conversation between Queen Gertrude and Ophelia’s brother Laertes. Gertrude describes how Ophelia fell into the river while picking flowers and slowly drowned, singing all the while.

Symbolism

Most of the flowers in Ophelia are included either because they are mentioned in the play, or for their symbolic value. Millais saw these flowers growing wild by the river in Ewell. Because he painted the river scene over a period of five months, flowers that bloom at different times of the year appear next to each other.

Millais always painted directly from nature itself with great attention to detail. The flowers are painted from real, individual flowers and Millais shows the dead and broken leaves as well as the flowers in full bloom. Millais’s son John wrote that his father’s flowers were so realistic that a professor teaching botany, who was unable to take a class of students into the country, took them to see the flowers in the painting Ophelia, as they were as instructive as nature itself.

Photography was invented in 1839, twelve years before Millais painted Ophelia. Photos were not as clear as they are today however. Millais’s Ophelia was more detailed than what photography was able to achieve at this time and was a unique way of representing the natural world.

What materials and techniques were used?

John Everett Millais's easel

© Tate, London 2003

The canvas

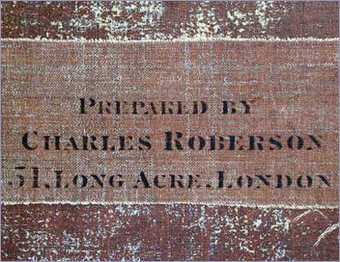

Millais bought two pieces of canvas for Ophelia from the art materials dealer Mr Charles Roberson on 7 June 1851 for 15 shillings. This type of painting, with two canvasses on a single stretcher (a wooden frame), one directly under the other, was sold by Roberson’s as a double canvas. The second canvas was used to cover the back of the painting to protect it.

Both canvasses were primed. This means they were covered with a glue solution and a ground. Millais used lead white paint as a ground. He then painted a layer of zinc white to make the canvas even brighter.

It is possible that at the beginning of each day Millais would mark out the area to be painted that day by covering it with white paint. He would then be working on a ‘wet white ground,’ and he would finish this area in detail while other parts of the canvas were still bare. In order to make the most of the bright white ground, he would mix colours as little as possible so that they remained pure, and apply the paint in single layers.

The colours

Millais was able to buy tubes of paint mixed by art material dealers that he could use straight away. New pigments were developed throughout the nineteenth century. Millais had a wide choice of pigments that came from minerals, precious stones, rocks, vegetables, insects and plants. Some of the new colours he used came about by the advances of modern chemistry. He used: lead white, zinc white, ultramarine ash, vermilion, chromium oxide, zinc yellow, chrome yellow, cobalt blue, Prussian blue, burnt sienna, Naples yellow, madder lake, ivory black and bone black. Millais’s greens were mixed greens of chrome yellow and Prussian blue, possibly from a tube of green paint.

Conserving Ophelia

Our conservators at Tate, the people who maintain and conserve our works of art, have studied Ophelia closely using various techniques. These help us understand how Millais painted. Looking at the painting under various light conditions can help us answer various questions:

Did Millais change the composition?

Ophelia under raking light © Tate Photography

In the photograph of Ophelia taken in raking light, we can see that Millais made relatively few changes to the composition. We can also see that the surface of the paint is very smooth. What we can see clearly are the cracks in the paint that have occurred over time. These cracks are caused by the ageing of the paint and the stretched canvas.

How was Ophelia painted?

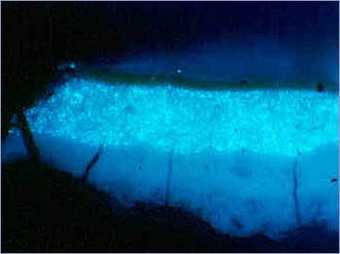

Cross section of Ophelia under U-V light © Tate, London 2003

In this U-V photograph of a ‘cross-section’ of a sample of paint from of Ophelia, we can understand the method by which the painting was made. The sample is viewed through a microscope so we can see the layers of paint and the thickness of the paint. The sample tells us that there is a layer of lead white underneath a layer of zinc white.

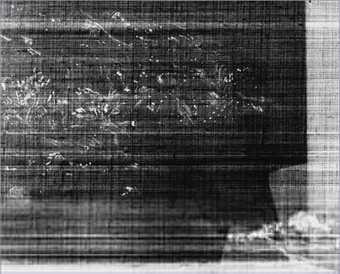

Did Millais add or remove any elements?

Ophelia under infra-red © Tate Photography

In this picture of Ophelia taken using infrared reflectography, we can see a slight shift in the position of the weeping willow. Many paint pigments are more transparent to infra red radiation than to visible light. The greater transparency of the paint enables us to see any drawings under the paint.

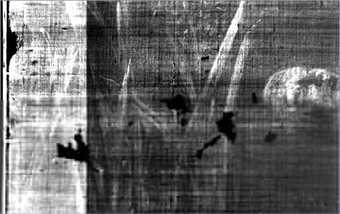

Was Millais reusing an old canvas?

In this X-radiograph image, we can see that Millais did not re-use this canvas or make any major compositional changes. X-radiograph images show obscured paint layers and changes of design that an artist has made. Millais carefully planned his work. We can see the dense metal tacks used to secure the canvas to the stretcher as well as staples used to re-attach the canvas to the stretcher after the canvas was taken off for relining. The lead white areas of the painting and the canvas weave are clearly visible as are the re-touchings that appear as black marks.

What's on the back of the painting?

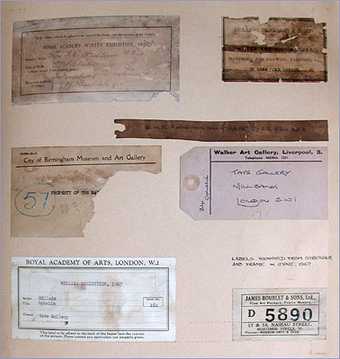

Labels removed from the back of Ophelia © Tate, London 2003

Roberson's stamp © Tate, London 2003

By looking at the back of a painting, you can learn a lot about its history. The back canvas layer of Ophelia was removed when the painting was lined in 1967, and the canvas and the information on it were closely recorded and preserved. In the photograph above, we can see the trademark stamp of Charles Roberson, the colourman who Millais bought his canvas from. It has been applied as a stencil. This can help us date the painting. Researchers were able to trace the archives of Charles Roberson and find out how much Millais paid for the canvases and when he bought them.

The back of the painting can also show us the history of where the painting has travelled and who owned it. When a painting is loaned to other galleries often a stamp is attached to the back of the canvas. We can see that it used to be the property of the National Gallery. The Tate Gallery was originally part of the National Gallery although in a separate building at Millbank.

We can see the painting appeared in the 1898 Royal Academy Winter Exhibition. Beside this there is the original purchase stamp of the canvas from Charles Roberson & Company. We can also see a darkened label with the words: ‘Farrer, H., Wardour Street, Soho “Ophelia”, By J. E. Millais, A. R. A. which indicates one of Ophelia’s original owners. There is a City of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery stamp. A Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool label which relates to the 1967 exhibition which began in London at The Royal Academy, the stamp for which can also be seen.

The James Bourlet & Sons Ltd. stamp shows us that one of the museums used this fine art packing company and frame makers to pack and transport this work of art.

Ophelia's Travels

Bowerswell, Perth

21st Sep 92My dear Mrs Tate

We were greatly delighted to hear Mr Tate has bought “Ophelia”. This is indeed good news and gives Sir Everett great pleasure. Tell Mr Tate I do congratulate him…

Ophelia was bought from Millais on 10 December 1851 by the art dealer Mr Henry Farrer for 300 guineas. Mr Farrer already owned several works by Millais. Farrer sold it to a keen Pre-Raphaelite collector called Mr B.G. Windus who then sold it in 1862 to a Mr Graves for 748. Mr Gambart owned it from 1864, followed by a Mr W. Fuller Maitland from 1872 and again in 1892. Sir Henry Tate bought it in September 1892, and then presented it to the nation as part of the Sir Henry Tate Gift in 1894.

What do the critics think?

Ophelia has received both positive and negative criticism since Millais began painting it in 1851. Read a variety of opinions on Ophelia from 1851/2 to the present day.

Mr Millais’s talent is budding into undoubted genius. We have no hesitation in saying that he had produced the two most imaginative and powerful pictures in the exhibition. Ophelia is startling in its originality. The beholder recoils in amazement at the extraordinary treatment, but a second glance captivates and a few moments’ contemplation fascinates him.

The Morning Chronicle, 1852

Ophelia was painted when he was 22. A painting on a minituristic detail on a non-minituristic scale, it is a tour de force of detailed depiction which at the historical point when photography was just emerging as a visual threat, out-records the recording power of the photograph. Art-historically. It marks a last stand in the war of the painter as sole guardian of visual truth. A photographer could get a woman to lie fully clothed in a stream but not a robin to perch above her head. The painter, Millais’s picture argues, has an imaginative and emotional advantage over the photographer. Ophelia, is passionate without the melancholy yearning of a young man waiting for love to happen; and imbued with a the delight in nature instilled by his fisherman grandfather, Ophelia’s stream, apart from anything else, is a fry fly-fisherman’s dream.

John McEwan, date unknown

Today, his drowning Ophelia (1852) is the most popular work in the Tate Gallery. Earlier this year a visitor from Australia, arriving at Millbank, burst into tears to find Ophelia away on tour in Japan. Its fame derives, of course, from the story of its model, the Pre-Raphaelite mascot Elizabeth Siddal, who lay wearing an antique brocade gown in a tin bath-tub to simulate Ophelia’s last moments. The bath water grew colder and colder and – so the tale goes – Lizzie contracted pneumonia, aptly foreshadowing her own untimely death as well as that of Shakespeare’s heroine.

‘Plenty to leave out’, by Jan Marsh, Literary Review, June 1998

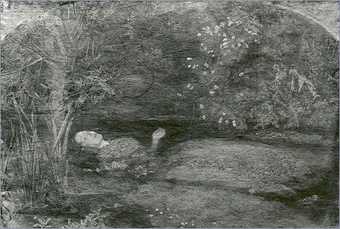

Other Ophelias

Ophelia is a very popular topic for artists. Shown above are various images of Ophelia, depicting the story in different ways. For example Arthur Hughes’s work of Ophelia exhibited at the same time as Millais’s at the Royal Academy, shows Ophelia before she slips into the river. J. W. Waterhouse produced three paintings of Ophelia. In his second painting of 1894, Ophelia sits on a branch of a tree, as she fixes poppies and daisies in her hair.

Please note Ophelia is touring and will not be on display until October 2019.