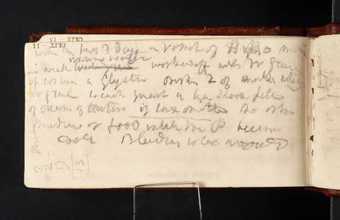

'Inscriptions by Turner' in Itinerary Rhine Tour sketchbook 1817

Tate D12545

In his Itinerary Rhine Tour sketchbook of 1817, J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) inscribed a hand-written note listing the possible remedies for dodgy bowels or the ‘Fever of Diar[rhoea] or Vomiting’, as he put it. In full, Turner’s note reads:

With the fever of diar[rhoea] or vomiting H […] m[?ixed]

in weak warm water washed off with W Gruel

If costive a Glyster Drink 2 of water whey

or Gruel to each quart a tea spoon full

of cream of tartare if lax motion No other

medicine or food until the P becomes

cooler Bleeding to be avoided

During his extensive continental travels, Turner would have stopped to take refreshment at various and possibly insalubrious taverns, where the chance of becoming prey to colonies of lurking microbes was high. The threat of attack might come, for example, from a slice of that darkening leg of ham behind the bar, or that disgruntled cook shy of hand washing or, indeed, that highly suspect toilet out the back.

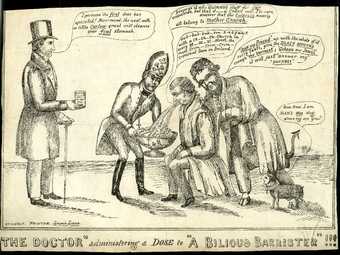

Anonymous

'The Doctor' Administering a Dose to 'A Bilious Barrister'!!! 1833

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

For vengeful tummies it was suggested to Turner that he make a mix of ‘weak … warm water washed off with W Gruel’ and ‘if costive’ (constipated), choose a ‘Glyster Drink’ made with ‘2 of water whey or gruel to each quart a tea spoon full of cream of tartare’. In the case of a ‘lax motion’, Turner writes that, ‘No other medicine or food’ must be ingested ‘until the P becomes cooler’ (the significance of ‘P’ can be left to the imagination). The note concludes with ‘Bleeding to be avoided’, a reference to the gory pseudo-scientific practice of bloodletting.

So, are these remedies quackery or could they have actually helped to relieve symptoms? Gruel, for example, may have indeed been a wise choice. This food consists of some type of cereal – oat, wheat, or rye flour, or rice – boiled in water or milk. A thinner version of porridge, gruel would have been a light and non-irritating form of nourishment for a sickly stomach. Cream of Tartar, meanwhile, combined to form a ‘Glyster’ drink (an enema), is a historical laxative. Be warned, however! The ingestion of large quantities of cream of tartare could produce entirely the opposite and equally undesirable effects of nausea, diarrhoea and gastrointestinal inflammation.

This is not the only medical recipe to have been jotted down by Turner: others include an ‘Emetic’ and ‘Purge’ treatment for the ‘Maltese Plague’ of 1813; a remedy for cholera using the oil of the Cajeput tree; a cure for ‘the bite of a mad dog’ (rabies); and even a treatment for the venereal disease gonorrhoea which involved injecting a solution of copper sulphate crystals via a painful-sounding Genital Insufflator.