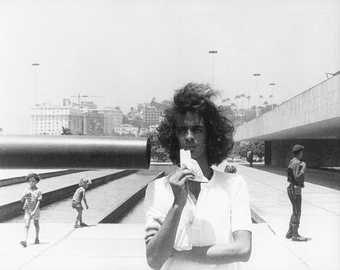

Cildo Meireles in front of the Monument to the Unknown Soldier, Rio de Janeiro 1974

Photo: Luiz Alphonsus

Who is he?

Cildo Meireles is a conceptual artist born in 1948 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He live and works in Brazil. His work often explores scale, ranging from a tiny cube the size of a fingernail in his piece Southern Cross, to large scale installations which fill entire rooms. Another key element of his work is the use of participation, which is often central to the idea behind the piece:

My work always searches for some kind of communion with this indefinable broad entity called the public.

‘Gerardo Mosquera in Conversation with Cildo Meireles’, Cildo Meireles, Phaidon, London, 1999

Cildo Meireles Fontes (detail) 1992/2008

Photo: Tate Photography © Courtesy the artist

What is conceptual art?

This term refers to an area of art where the artist places a greater importance on exploring an idea, or concept, than the artwork itself. Therefore, often, the piece is secondary to the process or performance which creates it. Find out more about Conceptual Art

For Meireles the existence of conceptual art was particularly important due to the poverty and precarious situation in Brazil:

Conceptual art… [affirms] anyone’s ability to make art, even when deprived of economic or technical conditions… It is not, however, a matter of aestheticising poverty, but of giving a voice to a multitude of individuals.

What are his Key works?

Cildo Meireles Red Shift I: Impregnation (detail) 1967–84

Photo: Tate Photography

Collection Inhotim Centro de Arte Contemporânea, Minas Gerais, Brazil © Cildo Meireles

Red Shift is a piece which spans three rooms. The first room, entitled Impregnation, could be someone’s living room, yet everything except the white walls, is red:

Curiously enough, I was helped by a tabloid called Balcão… you could pretty much buy or sell anything in it. The paper ran a front-page headline announcing my interest in exchanging or buying objects in the colour red.

The second room, Entorno, shows a tiny bottle which has spilt an impossibly large quantity of red liquid over the floor. The third room, Shift, consists of a running tap which gushes out red water.

During his solo exhibition at Tate in 2008 Meireles recreated an ongoing project of his named Meshes of Freedom. The artwork relies on the participation of the audience to join the intersecting pieces. Watch the video to discover more about the piece.

TateShots: Cildo Meireles

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 7 x exhibition copies (detail) 1970

Photo: Tate Photography

In 2014, Tate Liverpool’s Art Turning Left exhibition showcased Meireles’ piece Insertions into Ideological Circuits, a collection of Coca-Cola bottles which began in 1970. Although unremarkable when empty, when they are filled with the brown liquid political phrases such as Yankees Go Home’, or instructions for how to make a ‘Molotov cocktail’ appear. After use the glass bottles would be returned to Coca-Cola, recycled and then returned into circulation. This meant the work would be seen by unsuspecting customers across the world.

Meireles saw the cola bottles as an opportunity to subvert capitalism- in particular the influence of American brands entering Brazil around that time. This Insertion was one of a series which also included adding slogans to banknotes.

Cildo Meireles

Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Cédula Project 1970

Ink on banknote

7 x 15 cm

Photo: Wilton Montenegro © Cildo Meireles

Meireles felt it was important that the work was anonymous, lacked ownership and required participation through the act of circulating the items.

The insertions are a negation of authorship, of copyright. They aren’t works of art, they are propositions for action and participation.

What do the critics say?

There is a rogue physicality to much of his work, yet it also manifests a formal elegance and economy.

James Hall, The Guardian, 2008

Ignore Meireles at your peril: his work is exciting, fresh - and eminently accessible.

Alistair Sooke, The Telegraph, 2008

A work by Meireles … [has] its roots in social reality – a reality often harsh but marked by human resilience and inventiveness.

Guy Brett, Frieze, 2008

Cildo Meireles Glovetrotter (detail) 1991

Photo: Tate Photography © Courtesy the artist

Meireles in quotes…

Sure, we’re always influenced by what we did before… We’re all a bit like snails, carrying around our house, our universe.

I am interested in this relationship between the work of art and the viewer. Of course art can exist without a viewer, but it wouldn’t be so useful.

Interview with David Baker, Financial Times, 2014

We do political work when we are compelled to react to events. In some way you become political when you don’t have a chance to be poetic. I think human beings would much prefer to be poetic. I think every human being would like to have peace, to enjoy life, to have good food, good sex, good wine, good friends and pleasure. Maybe this will never be possible … Maybe we have a need to know the truth.

Interview with Guy Brett, Frieze, 2008